Europe ramps up arsenal with Ukraine helping drive effort for potential Russia war

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (photo: Getty Images)

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (photo: Getty Images)

RBC-Ukraine analyzes how Europe's defense industry is strengthening its capabilities in the face of the Russian threat and how Ukraine can help.

Key questions

- What are key countries doing in the defense sector?

- Why doesn't everyone want to strengthen their defenses?

- How is Brussels helping?

- What can Ukraine offer Europe?

The sabotage of a railway in Poland used to supply weapons to Ukraine is yet another manifestation of Russia's hybrid war against Europe, but it is far from the first. The number of Russian hybrid attacks quadrupled between 2022 and 2023 and tripled between 2023 and 2024, according to data from the US Center for Strategic and International Studies.

These include the arson attack on the Marywilska 44 shopping center in Warsaw in May 2024, the fire at IKEA in Vilnius, attacks on submarine cables in the Baltic Sea, and the severing of telecommunications lines. Poland, the Baltic states, Finland, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Norway suffer from these attacks most often — and they are the ones who most actively support Ukraine.

At the same time, the intelligence services of the Alliance member states regularly warn of the danger of a Russian invasion in the next 2-4 years. Against the backdrop of the reduction of US troops in Europe, this creates considerable risks – it is necessary to arm ourselves and, at the same time, provide Ukraine with weapons that it cannot produce itself.

Europe understands these challenges and is preparing for them. At the beginning of the year, RBC-Ukraine reported on the European defense industry's attempts to gain momentum. Much has changed since then, but the problems persist.

Europe's progress

According to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, in 2024–2025, most of Europe's military aid came directly from new production orders. In total, Europe has allocated more than €130 billion in military aid to Ukraine over three years of war, surpassing US supplies for the first time.

Satellite images reveal a massive expansion of European defense factories, with 150 companies increasing their floor space by 7 million square meters, with a focus on ammunition and air defense systems. This is three times faster than before Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk at the site of the sabotage (photo: Getty Images)

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk at the site of the sabotage (photo: Getty Images)

In August, Rheinmetall opened a factory in Unterlüß, Germany, to produce artillery shells – the largest in Europe. Another factory is set to begin construction in Lithuania in November and is expected to launch in 2026.

The situation remains more complicated when it comes to tank production. The German company KNDS (formerly KMW) plans to produce 58 new Leopard 2A8 tanks annually. Although this is twice as many as a few years ago, the scale is still not particularly impressive.

Drone production has doubled in two years and is expected to double again by the end of 2026, thanks to new factories in Germany, Poland, and Lithuania. Europe plans to reach a production volume of up to 12,000 drones per month.

The main bottleneck in European defense is the production of gunpowder and other explosives. Although production has increased by 50% this year, defense companies still complain about shortages. To overcome this problem, Rheinmetall is preparing to expand gunpowder production in Romania and Bulgaria.

Defense spending

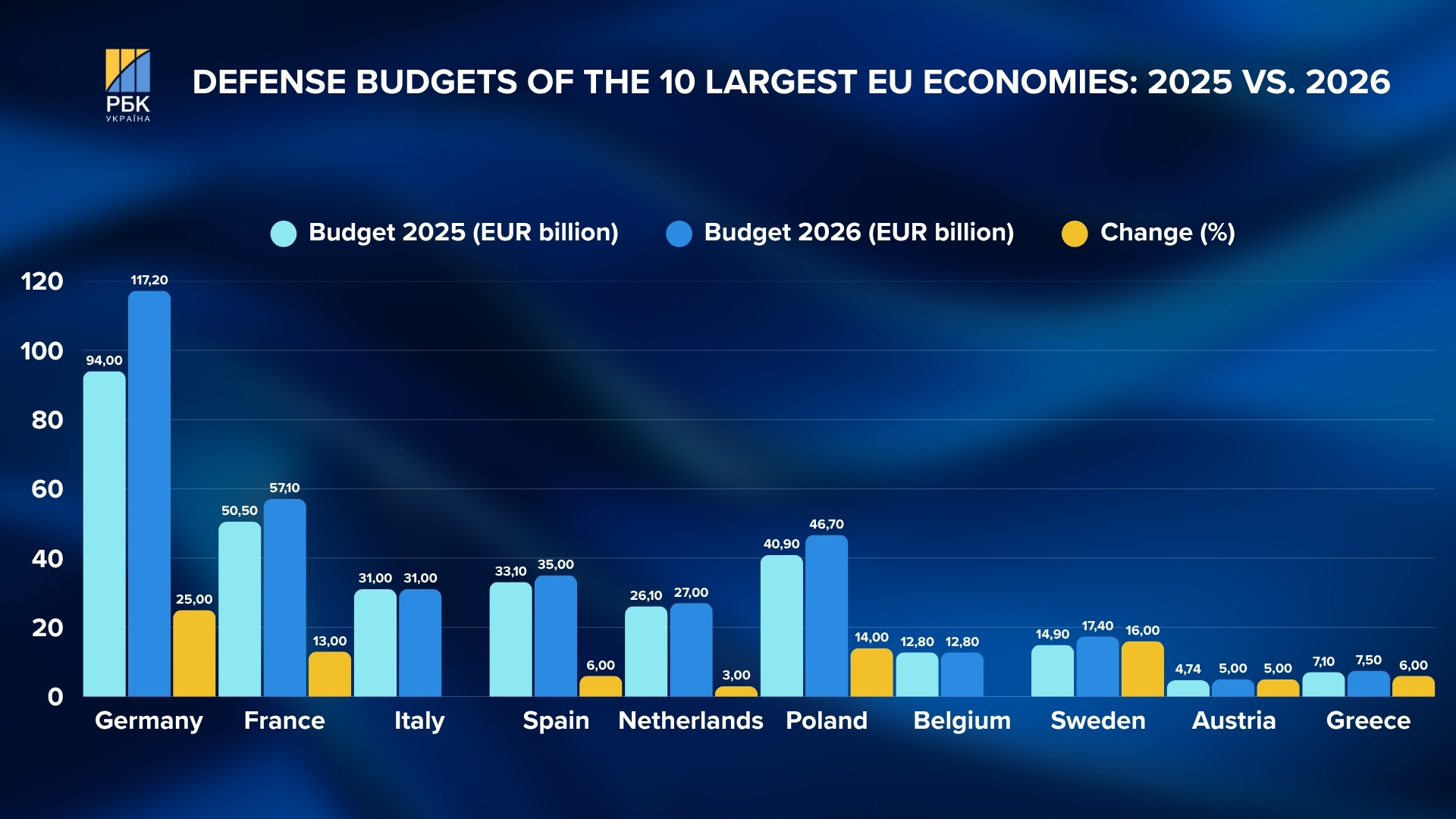

At the NATO summit in The Hague in June this year, European members of the Alliance agreed to the US demand to increase their defense spending to 5% of GDP by 2035. This increase has already been factored into next year's budgets; however, not all countries are ready for decisive action.

In absolute terms, Germany plans to allocate the largest share to defense. Compared to this year, the increase is 25%. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, and Poland are also among the leaders.

However, Italy, Belgium, and Slovakia, for example, do not plan to increase their defense budgets in 2026. The Netherlands is increasing its spending by only 3%, and Spain by 6%. However, the latter has abandoned NATO's overall target of 5% of GDP and will limit itself to 2.1% for key defense capabilities.

RBC-Ukraine infographics

RBC-Ukraine infographics

How Europe is preparing its arsenals for war with Russia and how it is helping Ukraine Countries with the highest growth in spending, such as Poland and the Baltic states, plan to allocate a significant portion of their budgets to the purchase of new weapons and investments in defense production — often more than half of their funds, with an emphasis on drones, air defense, and ammunition.

In Italy, Belgium, and Slovakia, the share of the budget allocated to purchases and investments remains lower. They focus on long-term projects under the auspices of the EU and maintain existing forces, without radical changes in the structure of expenditures.

Reasons for differences

Attitudes toward national defense depend on a country's proximity to Russia. However, this is not the only factor. In several countries, the influence of populists – right-wing or left-wing – remains decisive. In some places, they have come to power (e.g., Italy or Slovakia), in others, they are in opposition. They are held back only by the mainstream parties uniting against them (as in Germany), and in others, they sow chaos, paralyzing the decision-making process. But they invariably appeal to people's material interests here and now rather than investing in defense for the future.

"Populists in countries such as Czechia, Slovakia, and Germany continue to enjoy support because they capitalize on a combination of war fatigue, rising living costs, and the feeling that the so-called elites in Brussels or Kyiv care more about geopolitics than the everyday problems of ordinary people," Rasto Kuzel, executive director of Memo 98 (Slovakia), an organization that monitors political processes in Europe, tells RBC-Ukraine.

According to him, the direct attack by Russian drones on Poland and dozens of other hybrid operations demonstrate the need to transition to a military economy. However, this is extremely difficult—the countries of the European Union are democratic, and their leaders are forced to consider the political implications of their actions. In Germany, this difference is particularly evident.

"In the east, in the former GDR, the far-right Alternative for Germany has a strong position, taking advantage of historically low levels of trust in institutions and the West, while the western part of the country remains more pragmatic and firmly attached to European-Transatlantic structures in matters of defense and support for Ukraine," Kuzel notes.

Opening of the Rheinmetall plant in Unterlüß, Germany (photo: Getty Images)

Opening of the Rheinmetall plant in Unterlüß, Germany (photo: Getty Images)

The expert emphasizes that in the northern and Baltic countries, the threat from Russia has never been forgotten — it is part of their identity and political reality.

Therefore, even local populists understand that denying the need to strengthen defense would be political suicide for them. Their populism is of a different nature: it is not pro-Russian, but based on the ideas of state efficiency, transparency, and national resilience, rather than flirting with authoritarian regimes. At the same time, further away from Russia's borders, the situation is different.

"Throughout the Central European region, there has long been a lack of strong consensus on the pro-Russian trap and society's immunity to disinformation, allowing populists to promote simple slogans about national interests and peace," Kuzel emphasizes.

The situation in Czechia is specific. Until recently, a government of mainstream parties was in power there. It prepared a powerful defense budget with a planned 34% increase in defense spending, but in October, the populist ANO party led by Andrej Babiš won the elections and will have to prepare its own version of the budget.

In the context of support for Ukraine, the new government is expected to pursue a less value-oriented but pragmatic and selectively beneficial policy. Babiš is not an ideological ally of Moscow—his business and political orientation are closely linked to the West and the EU, so he will not be interested in openly sabotaging aid to Kyiv or undermining European unity.

"At the same time, he will seek to minimize domestic political costs and, most likely, shift the Ukrainian agenda to the EU level: less public leadership, more technocratic and economically beneficial decisions," Kuzel adds.

The expert did not rule out the continuation of the Czech ammunition initiative or other forms of support for Ukraine, but probably in the form of profitable business for his entourage, rather than a manifestation of a firm value position. In addition, it is quite possible that at the pan-European level, Babiš will join situational blocking coalitions with Orbán and Fico if necessary, if this brings him negotiating advantages.

Support from Brussels

Recognizing the challenges of securing funds in each country, the European Commission is doing its best to help. This has become one of the priorities of its president, Ursula von der Leyen, and European Commissioner for Defense and Space, Andrius Kubilius.

In October this year, the EU Defense Readiness Roadmap to 2030 was approved. It stipulates that in five years, at least 55% of defense investments will go to European suppliers and 40% to joint projects. The roadmap introduced four flagship projects: the European Drone Defense Initiative, Eastern Flank Watch, European Air Shield, and European Space Shield.

The Commission has also established a special fund called SAFE (Security Action for Europe), which is intended to help EU countries finance production capacities and joint purchases. However, this is only the beginning.

"The proposals submitted by the countries are concepts that must be outlined in defense plans and submitted only at the end of November. In January, certain conclusions should be reached, and only then will work begin on how much money to allocate to all these projects," Hennadii Maksak, executive director of the Ukrainian Prism Foreign Policy Council, tells RBC-Ukraine.

Alongside this, the European Defense Investment Program (EDIP) is working to support the expansion of production capacities and coordinated procurement. However, according to Maksak, it is also only agreed upon between EU institutions.

Additionally, the EU has activated Permanent Structured Cooperation in Defense (PESCO), which brings together 26 member states in joint projects to invest in defense capabilities.

According to estimates by the European Defense Agency, fragmentation remains one of the biggest obstacles. There are currently 27 separate national defense strategies at the EU level, but no single map of defense capabilities. Additionally, it takes years for projects to move from the planning stage to production. Production chains are hampered by a shortage of critical components, especially explosives, propellants, and specialized materials. Most European companies use a make-to-order model, which increases delivery times and discourages investment in new production lines.

NATO summit in The Hague (photo: Getty Images)

NATO summit in The Hague (photo: Getty Images)

European Commissioner for Defense Andrius Kubilius summed up the EU's achievements by saying that this year, they have invested in capabilities, which are primarily capacity-building capabilities. At a hearing of the European Parliament's relevant committee on November 6, he noted that the European Union still suffers from structural delays: Defense has always been national, coordinated by NATO, with the single market still not designed for defense. But for now, Europeans have to work with what they have.

"If we are talking about the European Union level, there is a certain bureaucratic lag, and they themselves are not happy with this. Kubilius is trying to push them forward a little. But until these rules are changed, we will have to use them," Hennadii Maksak tells the agency.

How Ukraine can help

In this situation, oddly enough, Ukraine can offer its assistance to Europe, in particular through the export of its own weapons. Ukrainian companies can provide this with surplus capacity.

"To be honest, we cannot afford to export all our weapons. Some weapons are essential to us. We are ready to work with naval drones. In my opinion, we also have other weapons, including artillery systems, although, to be honest, there are not many of them, but we are currently producing a lot of them," the President of Ukraine said on November 3.

For their part, European countries, as well as the US, are already actively showing interest in Ukrainian developments.

"It is economically unfeasible to shoot down cheap Russian drones with expensive missiles, so Europe is now looking for solutions that are available in Ukraine. These are interceptor drones, electronic warfare systems, and any anti-drone measures," Kateryna Mykhalko, executive director of the Technological Forces of Ukraine, tells RBC-Ukraine.

In addition, she says, countries that share a border with Russia, including Estonia, are naturally interested in a broader arsenal of drones.

Ukrainian naval drone Magura (photo: Getty Images)

Ukrainian naval drone Magura (photo: Getty Images)

As noted by Rustem Umerov, Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, the first real contracts for the export of Ukrainian weapons are expected in the second half of 2026. By the end of this year, the first two export offices will open in Berlin and Copenhagen. They are intended to simplify cooperation and sales of surplus Ukrainian weapons, as well as products manufactured in collaboration with European companies.

"When we can become a full-fledged partner for the European Union in armaments, it will be beneficial for both sides. Europe can gain access to the military technologies it needs to defend itself. Ukraine can integrate its own industry with the European one," Mykhalko emphasizes.

Additionally, this means financial resources and investments to support Ukraine's defense capabilities. Ultimately, Ukraine's experience in manufacturing the latest drones and anti-drone technologies can help adapt and modernize EU bureaucratic procedures, making the process more dynamic.

"Bureaucracy gives advantages to manufacturers because there is financial predictability, which the Ukrainian sector lacks. However, since drones are the latest weapons, not all standards are adapted. Ukraine could bring its experience to help refine these procedures to make them more flexible and promote faster development," Mykhalko concludes.

At the same time, it is important to avoid corruption risks and bureaucracy within Ukraine, particularly in light of the Mindichgate scandal.

In August, Rheinmetall CEO Armin Papperger, who had previously compared the pace of construction of Ukrainian and German ammunition factories, emphasized that the level of bureaucracy in Ukraine is very high, and that does not please him.

The factory in Germany is already operational, but there has been no news about the launch of Ukrainian production. Although the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense responded quickly to the criticism, promising to improve coordination mechanisms, this story remains indicative. But it should not overshadow the main point: Ukraine and Europe find themselves in a situation where cooperation is no longer a matter of goodwill, but a matter of survival.

European defense requires time, investment, and political consensus—and all three resources are limited. Ukraine, on the other hand, has combat experience, technologies tested under fire, and production capacities that can complement European factories. Therefore, in the current circumstances, it is important not to delay their integration.