Peace or blackout? Ukraine braces for toughest winter as Trump considers his next move

The main risks this winter are linked to the war, missile strikes, and whether Trump's peace efforts will succeed or fail (Collage by RBC-Ukraine)

The main risks this winter are linked to the war, missile strikes, and whether Trump's peace efforts will succeed or fail (Collage by RBC-Ukraine)

What challenges will the Ukrainian government face in the coming months? Should we expect a quick truce or brace for a continuation of the full-scale war? Will there be any breakthroughs at the front? Can Russia plunge the country into a blackout? And could public discontent boil over? Read the analysis by RBC-Ukraine.

Key questions:

- How was Trump persuaded to agree with Ukraine's vision for a ceasefire?

- Can Russian forces advance in Donbas?

- Should Ukrainians prepare for blackouts and cold radiators?

- Could public discontent lead to protests?

"We'll see what happens." This signature phrase of Donald Trump aptly describes the mood among RBC-Ukraine's government sources as winter approaches.

After several attempts to end the Russia–Ukraine war in one move, the US President appears to have taken a pause. His recent comments on Ukraine no longer feature the familiar two-week timeline. Instead, he now speaks of a six-month horizon, saying that within that time, the world should assess the impact of newly imposed sanctions against Russia.

"We agree that the sides are locked in fighting, and sometimes you gotta let them fight, I guess," said the US President during a meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Still, it doesn't seem that Trump has shelved the issue entirely. At least in the background, his attempts to reconcile Kyiv and Moscow and push for a ceasefire are expected to continue.

"I have this feeling that amid all these talks, one day suddenly—boom—and in a week or two, we'll have a ceasefire," a source close to the president told RBC-Ukraine.

Nevertheless, both that source and other government officials RBC-Ukraine spoke with in recent weeks agree: the baseline scenario for the next 4–6 months remains the continuation of the war in its current form.

During this period, the Ukrainian government will have to tackle several critical challenges: maintaining international, and above all, US, support (without provoking an ultimatum from Trump); holding the front lines, especially in Donbas; keeping the country running amid intensified strikes on the energy grid; and managing public frustration caused by those very attacks and the resulting everyday hardships.

Trump and ceasefire

Over the past few weeks, Donald Trump has taken Ukrainians on quite the emotional roller coaster. First came his veiled hints about providing Tomahawks. Then, a sudden phone call to Putin, the announcement of a Budapest summit, and a rather cool reception for Volodymyr Zelenskyy at the White House. Then, just as abruptly, the summit's cancellation and sanctions against Rosneft and Lukoil.

When the dust settled, all the players were left without a clear sense of what comes next — who should travel where, who should call whom. Part of that agenda will likely be shaped by the peace plan Ukraine is developing with its allies. But it's equally clear that any peace plan won't matter much if Moscow still burns with the desire to fight on.

"Trump didn't expect the Russians to be such liars," a source close to the Ukrainian President told RBC-Ukraine. "When he dealt with them during his first term, it wasn't at this scale — it was just politics. Now it's a full-blown war, people are dying every day."

In recent months, Trump's attitude toward the Russians has changed (Photo: Getty Images)

Another insider expands on that thought:

"We've had tough moments with the Americans, too. But the difference is, we always spoke openly about our position — we could argue, disagree, but eventually find solutions. The Russians, on the other hand, say 'yes, yes, yes, here's a pile of new proposals — and then they cheat on every single point."

That's why, right now, the risk that Trump might start playing into Moscow's hands or twisting Kyiv's arm looks relatively low. During his second term, he's already tried several approaches. Pressuring Ukraine didn't work. Trying to build economic ties with Moscow based on shared interests — the war kept going anyway.

So now he's turned to a new tactic: sanctions. That's notable, given Trump's general skepticism about sanctions as a tool. Yet just days after the US sanctioned Rosneft and Lukoil, Russian officials protested so loudly about how harmless the move was that it was obvious the sanctions had hit a nerve.

The hasty and seemingly fruitless visit to the US by Kirill Dmitriev, who was publicly called a "Russian propagandist" by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, only confirmed that.

Trump's next moves will increasingly be shaped by the upcoming midterm elections, exactly a year away.

"Trump's team thought that multiple wars wrapped up, especially in Gaza, would help them heading into the midterms," an insider from the Ukrainian government told RBC-Ukraine. "But it turned out that for Republicans, Israel matters less than Gaza does for Democrats. Meanwhile, we managed to spark genuine interest in Ukraine among the GOP base."

Polls back that up. According to Public Opinion Strategies, support among Republican voters for congressional military aid to Ukraine rose from 39% to 47%. Sixty-three percent support providing Tomahawks; 64% blame Putin for the ongoing war (only 13% blame Zelenskyy). The biggest shift in perception came from Trump's core base — conservative Christians.

This puts real limits on Trump's freedom of maneuver when it comes to Ukraine. Especially since Kyiv has convinced him that voluntarily giving up control over parts of Donbas — something Russia still demands — is a non-starter.

Sources familiar with the discussions say Trump, in his usual brash style, tried several times to test Ukraine's red lines: suggesting that if Kyiv wants concessions from Moscow, it should make some first.

Ukraine has, in fact, already made several gestures, such as agreeing to a ceasefire without preconditions. But now Washington has been told clearly, through multiple channels, that ceding Donbas is impossible for several reasons.

First, it would set a precedent Russia would surely exploit again — damaging US positions in the future. Second, Ukraine is only "losing Donbas" in Russian Defense Ministry briefings. The real situation on the ground is very different, and it could take Moscow months, even years, to capture the entire region. Third, the Ukrainian people firmly reject such concessions, and Europe wouldn't accept them either.

Lately, Trump seems more receptive to the arguments of Secretary of State Marco Rubio, often labeled "anti-Russian" and "pro-Ukrainian" (though that's an exaggeration). Ukraine has influenced Rubio partly through the Cuban issue: Cuba has recently become a major supplier of "cannon fodder" for the Russian army, angering the Cuban-American community in the US. For Rubio, the son of Cuban immigrants, that hits home. And just days ago, Ukraine was among the few nations at the UN to vote against lifting the embargo on Cuba, siding with Washington.

All this convinced Trump to publicly declare that any peace talks must start from the current front line. But that's exactly what Putin rejects, and he's now doing everything he can to push that line further west.

Situation on the front line

Putin's pseudo-compromise — offering to settle for Donetsk and Luhansk regions instead of demanding all four occupied territories — pursues one not-so-obvious goal: to trigger a political crisis inside Ukraine. Moscow is betting it can achieve that regardless of whether Kyiv accepts or rejects its ultimatum.

From Putin's perspective, if the Ukrainian government agrees to this ploy and voluntarily gives up Donbas, it will fracture Ukrainian society from within. But if Ukraine chooses to keep fighting and still ends up losing the Donetsk region, at the cost of heavy casualties, the internal shock could be just as severe.

That's why Russia continues its active offensive in the East, hoping to break either Ukraine's resistance or its defensive lines. The epicenter of fighting this winter remains the Donetsk region, which the invading army reportedly plans to fully capture by the end of February. The biggest threat now looms over the city of Pokrovsk, where urban combat is already underway.

Back in September, military sources said that the outlook for Kupiansk in the Kharkiv region, where battles were also raging, was even more pessimistic than for Pokrovsk. The enemy has been trying to take Kupiansk for two years and Pokrovsk for over a year.

But now those assessments have flipped. In Kupiansk, Ukrainian forces have managed to stall the Russian blitz push and launch counteractions, while in Pokrovsk, the situation has deteriorated rapidly in recent weeks, edging toward the point of no return.

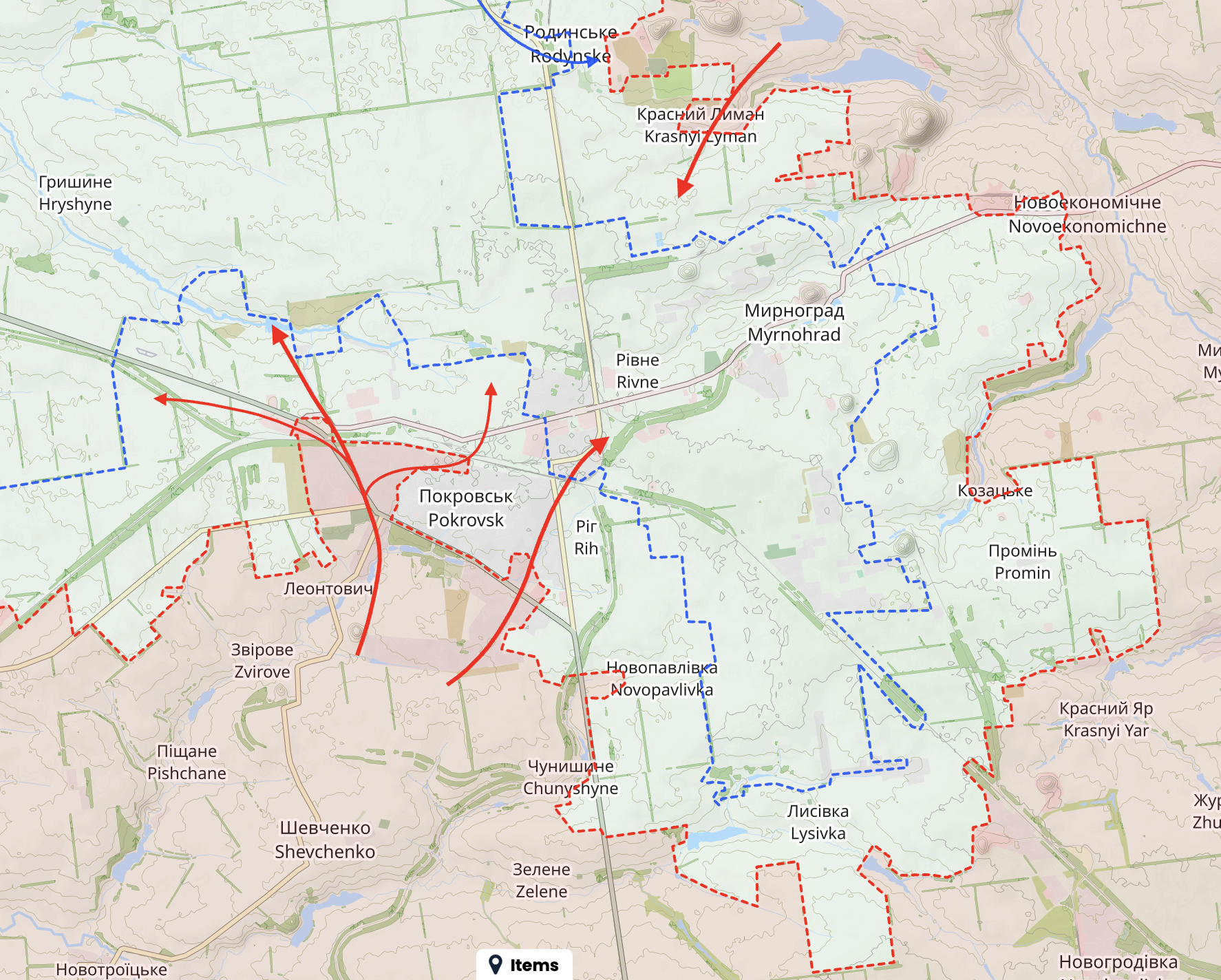

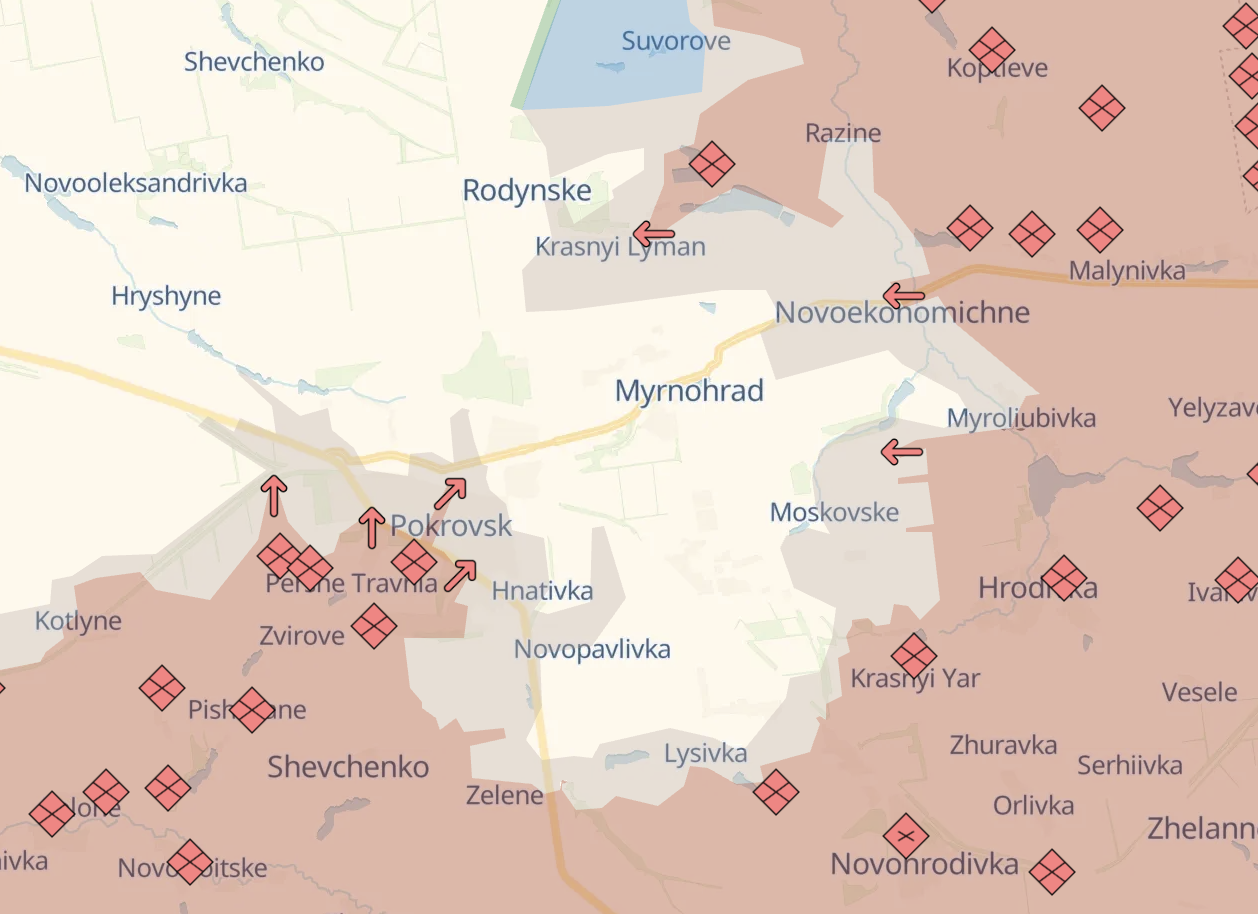

Pokrovsk. BlackBird and DeepState maps

A particularly vulnerable area is the Zvirove district southwest of Pokrovsk, where last summer Russia's 2nd Combined Arms Army began pushing into the city. More recently, Russian units from Kotlyne infiltrated the western part of Pokrovsk, entering the industrial zone and approaching the road to Pavlohrad.

According to the outlet's sources, several hundred, possibly up to a thousand, Russian troops are now inside Pokrovsk. A railway line divides the city roughly into northern and southern halves. On various OSINT maps, the southern part is already marked as a gray zone or even red, meaning under Russian control.

Since the situation is highly fluid, it's difficult to say exactly who controls which areas. What can be stated clearly is that there is no encirclement or cauldron yet, though the enemy seems intent on creating one. Russian forces do not control the entire city, but they are pushing intermittently into its central, western, and northern sectors, engaging in close combat.

The situation is further complicated by simultaneous Russian pressure on Pokrovsk's twin city, Myrnohrad, from the east and north. Open-source maps show both towns trapped in a pocket with increasingly difficult logistics — Russian FPV drones frequently target Ukrainian supply routes. Ukraine's Defense Forces are working to stabilize the situation in and around Pokrovsk, with intelligence-service units from the Defense Ministry joining local defenders to reinforce the line.

"It's extremely hard to predict how this will play out. We haven't yet reached the point of no return, but we're close," one military source told RBC-Ukraine. "The fate of Pokrovsk will be decided in the coming weeks. If we lose Pokrovsk, we'll likely have to give up Myrnohrad almost without a fight, and from there the problem will spread across the northern Donetsk region."

If Russia achieves its goals around Pokrovsk, sources believe it will next shift its focus to the Kramatorsk-Kostiantynivka urban area. That would mean intensified pressure on Lyman, Siversk, and Kostiantynivka, and likely new attempts to capture Kupiansk.

Another risk this winter is Russia's strategy of a thousand cuts. Aware that Ukraine faces a shortage of manpower, Russian forces probe for weak spots in the defensive line. By opening new fronts, they force Ukraine to put out fires — pulling troops from other sectors and stretching its front line even thinner. The danger lies in the possibility that the enemy could then strike a currently stable area with a sudden, concentrated assault.

Shelling of Ukraine's energy sector

"We don’t need light to see that Russians are a*******. In that sense, nothing has changed since 2022," a source close to the government told RBC-Ukraine, commenting on the current and future strikes against Ukraine's energy infrastructure.

Moscow has clearly made attacks on infrastructure its main strategy for the coming months, and everyone interviewed agrees on that.

"The Russians are trying to destabilize us not only on the front line but also in the rear. Putin has taken a deliberate course of attacking our energy and oil-and-gas infrastructure — I think he'll keep doing that. For us, it's important to respond so that Russian citizens feel the same pain we do. I believe our energy workers will cope, but we can't rule out further power outages," said Fedir Venislavskyi, member of the Ukrainian Parliament's Committee on National Security, Defense, and Intelligence.

Since early autumn, the Kremlin has resumed its campaign of strikes on Ukraine's energy system. At first, the enemy targeted local generation (thermal and combined heat-and-power plants) in the east, aiming to create an energy deficit there and increase the need for power transfers from other regions. Then the attacks shifted to transmission nodes, substations, grid junctions, and power lines in the east and center, trying to cut off electricity routes to consumers. Later, the strikes began moving westward, hitting thermal, combined, and hydroelectric plants in central and western regions to reduce Ukraine's maneuvering capacity.

This winter, the main risk is that Moscow will continue to hit any restored thermal plants. Another danger is mass attacks on ENTSO-E import–export nodes to complicate electricity imports. And a third, possible strikes on distribution units and main transmission lines from nuclear power plants, which could prevent them from supplying power to the grid and cause a full desynchronization of Ukraine's energy system — something similar to what happened in late November 2022.

However, this year's campaign differs from what Russia did three years ago. Now Moscow carries out more targeted, serial strikes. Back then, the goal was to trigger a quick nationwide blackout; today, it's a slow war of attrition — methodically wearing down the system.

Russia has also changed its tactics and choice of targets. It now mixes different types of weapons — cruise missiles, Shahed drones, and ballistic missiles. Some attacks are carried out solely with drones or ballistic missiles, without using strategic aviation or Kalibr missiles, making the strikes less predictable.

"Under the baseline scenario, we have enough generation capacity and import potential to cover peak hours. All outages happening now are controlled — ordered by Ukrenergo dispatchers and distribution system operators. That means the system is still under control and not collapsing," said Hennadii Ryabtsev, energy expert and director of special projects at the Psychea Science and Engineering Center.

Still, Ryabtsev adds, system stability doesn't mean Russia can't disable individual facilities.

According to him, a large amount of preparatory work was done during the off-season — reserve capacities and stocks of vulnerable equipment were built up. While an apocalyptic scenario is unlikely this winter, occasional power cuts are still expected.

The situation in Kyiv on October 10, 2025, when several districts of the capital were left without power (Photo: Getty Images)

"During repair works, both residential and industrial consumers will face temporary power limits. The duration will depend on the damage inflicted by Russia. Normally, even after major attacks, full restoration takes from a few hours to several days," Ryabtsev noted.

Besides the power grid, Russia has also been targeting gas infrastructure this season. Ryabtsev says Ukraine has enough gas in underground storage to get through winter. The government decided to buy an additional 1.5 billion cubic meters — a third more than the already purchased 4.6 billion.

Currently, 13.2 billion cubic meters of gas are stored underground, of which 8.5 billion are usable — the rest are long-term or buffer reserves. The energy sector will need around 3 billion cubic meters for the whole season.

The risk, however, lies in possible disruptions: if compressor or gas distribution stations are hit, gas may not physically reach consumers.

"If Russia continues to strike gas production, transport, and compressor facilities, we might face a scenario where domestic gas supply is limited for a few days, similar to electricity cuts, until repairs are made," Ryabtsev explained.

A government source told RBC-Ukraine that such strikes on gas infrastructure could be even more painful for civilians than electricity shortages, especially if the winter turns out cold. Yet, the aggressor is unlikely to freeze out Ukrainians entirely, though localized problems in some cities are quite possible.

Ukrainians' mood

Russia's campaign of mass missile strikes pursues several goals. One of them is to collapse Ukraine's economy as a whole, and especially its key component, the defense industry.

Naturally, power outages will disrupt production in some places and delay delivery of goods in others. At the end of October, the National Bank of Ukraine downgraded its growth forecast from 2.1% to 1.9%, citing strikes on energy infrastructure and gas production facilities.

Still, officials and experts interviewed insist that the projected economic losses don't look catastrophic. The primary reason is that, over the years of war, Ukraine's economy has undergone significant adaptation — becoming less dependent on energy and far more reliant on external financing. And Russian strikes tend to increase that external aid rather than cut it off.

"These massive attacks have once again drawn attention to us. We've already received a ton of help because of them — transformers, all sorts of batteries, and air defense systems. Many donors are more willing to help prevent a humanitarian crisis than, say, to fund strikes on Russian oil refineries," a government insider told RBC-Ukraine.

The same applies to Ukraine's military production. Of course, not all facilities can be relocated to the country's far west or abroad, or safely hidden underground. Some damage is inevitable, but sources of RBC-Ukraine note that it won't be critical.

According to virtually all of RBC-Ukraine's interlocutors, the main goal of Russia's strikes is to stir public discontent among ordinary Ukrainians — people whom Moscow hopes will pressure Kyiv to seek peace at any cost.

But even here, Putin doesn't have much to count on. Yes, frustration with darkness, cold, and daily inconveniences will grow, but it won't turn into calls for surrendering to Russian demands.

"Only one to three percent of Ukrainians support peace at any cost. Over 90 percent are firmly against any concessions just to end the war," says Oleksiy Antypovych, head of the Sociological Group Rating, in a conversation with RBC-Ukraine.

At the same time, the sociologist admits that the overall national mood has become more pessimistic. The same trend appears in the share of respondents who believe the country is moving in the right direction — a kind of barometer of public sentiment.

"But this discontent won't translate into political action," Antypovych explains. "Sure, people curse while walking up twenty-five flights of stairs, but they don't curse the Ukrainian government or the domestic system — they curse the enemy, the Russians. All blame is directed at them. We clearly understand who our enemy is."

Meanwhile, he adds, public sentiment is also becoming more radicalized. Roughly a quarter of Ukrainians say they would support radical political forces, which, as of now, don't really exist as formal parties.

"Imagine what that could mean if protests break out. It could all get sharp and far from peaceful, nothing like the 'cardboard protests.' But that's something for the postwar period. For now, people understand there's no point in attacking a government that, after all, hasn't betrayed the interests of Ukrainians or the Ukrainian state," Antypovych says.

***

The fourth wartime winter, by most accounts, will be the harshest yet. According to Ukrainian officials, Putin, with his trademark obsessive persistence, is convinced that this time he'll finally break Ukraine. He's failed before, but somehow believes this attempt will succeed.

There's no real reason to think so. "It'll be bad and difficult, sure, but Ukrainians' resilience has grown enormously over these years. If all this had hit back in autumn 2022, it would've been a different story," a source close to Zelenskyy concludes.