Why Poland criticizes Ukraine and how it can impact aid for Kyiv

Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Donald Tusk (photo: Getty Images)

Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Donald Tusk (photo: Getty Images)

Why the relations between Ukraine and Poland have gone bad, what lies behind harsh criticism from Polish officials toward Kyiv, the role of elections and historical conflicts, and will Warsaw support Ukraine further - read in the article below.

Contents

At the start of Russia's full-scale invasion, relations between Poland and Ukraine entered what could be called a "honeymoon period" despite the tragic circumstances. Previous disputes were set aside as Poland offered Ukraine extensive assistance – from delivering weapons to hosting millions of refugees, lobbying for Ukraine's interests in the West, and establishing logistical hubs for arms deliveries on Polish soil. For many Ukrainians, especially with airports closed, Poland became the primary "gateway" to the outside world.

However, this "honeymoon" began to fade over time. The first major warning signs came last year with widespread protests and border blockades by Polish farmers and transporters. In Ukraine, these actions were mainly linked to the intensifying political competition ahead of Poland’s October parliamentary elections.

A common view among Ukrainian political circles was that the issues would resolve themselves after the elections, especially if power shifted to the opposition led by Donald Tusk's Civic Coalition. While this transition occurred, problems, particularly concerning Ukrainian grain exports, remained unresolved.

For a time, Poland's new government avoided emphasizing historical disputes. However, it eventually began addressing them more sharply than its predecessors. In recent months, Polish officials' criticism of Ukraine has become a recurring theme.

On November 5, Polish Deputy Prime Minister Krzysztof Gawkowski criticized Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in an interview with Radio ZET, claiming he had "forgotten" about Poland's support. This came after Zelensky stated that Poland had not delivered MiG-29 fighter jets to Ukraine as previously agreed.

"I got the impression that the recent words of President Zelenskyy were unworthy of a politician who owes much to Poland. Equipment has been provided, citizens are cared for, and Poland is a great friend of Ukraine, a transportation hub. In such situations, I think one should say 'thank you', not complain," Gawkowski emphasized.

According to the Polish Presidential Office, Poland has allocated 4.91% of its GDP to aid Ukraine since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion. So, in terms of spending as a percentage of GDP, Poland, according to its own calculations, ranks first among countries that support Ukraine.

Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine and Poland in Kyiv – Andrii Sybiha and Radosław Sikorski (photo: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

Earlier, in September, a visit by Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski to Kyiv led to a diplomatic controversy. Polish sources claimed Zelenskyy reiterated that Poland's support for Ukraine was insufficient during their meeting. However, RBK-Ukraine's sources suggest Sikorski himself sought to use the visit for political gain and self-promotion, tying Ukraine's EU integration to resolving historical disputes in a particular tone.

During the visit, Sikorski also made a vague proposal to place occupied Crimea under a UN mandate.

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk stressed the importance of historical issues.

"Ukraine will not become a member of the European Union without Poland's consent. Ukraine must meet standards, and these vary – it's not just about borders, trade, legal, and economic standards. It's also about cultural and political standards," Tusk said in late August.

Such statements from various members of Poland's ruling coalition continue to this day.

Reasons behind anti-Ukrainian statements

Heightened rhetoric about Ukraine serves different purposes for various Polish politicians, explained a source familiar with Polish affairs in a conversation with RBC-Ukraine.

In May 2025, Poland will hold presidential elections. Current President Andrzej Duda is completing his second term and will not run again, sparking intense competition for the vacancy.

The ruling Civic Coalition has two leading contenders: Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski and Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski. While Trzaskowski appears to have stronger prospects, the final decision will depend on internal party primaries.

Meanwhile, the main opposition party, Law and Justice (PiS), lacks a candidate with the influence and charisma to challenge the government's pick. In addition, PiS is embroiled in ongoing and sharp internal conflicts.

As a result, government representatives are leaning into historical topics, traditionally a stronghold of their opponents, to outmaneuver them, according to RBC-Ukraine's source.

The Polish People's Party (PSL), whose leader and defense minister Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz has also been vocal in his criticism of Ukraine, is motivated by survival. Polls suggest the PSL might not pass the threshold to enter parliament for the first time in over 30 years, prompting sharp rhetoric as a bid for relevance.

However, Daniel Szeligowski, Coordinator of the Eastern Europe Program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs, believes the roots of these statements are deeper.

"Such statements about Ukraine are being made because, in essence, a consensus has already been reached among all politicians in Poland. They are all tired of how much President Zelensky constantly accuses Poland. And from the Polish side, there is no big difference now whether it is the ruling party, the opposition, the left or the right forces. They are all tired of these Ukrainian accusations," Szeligowski told RBC-Ukraine.

This political sentiment reflects a broader shift in public opinion about Ukrainians in Poland. According to a United Surveys poll conducted on October 21–22 for Wirtualna Polska, 43.6% of Poles believe relations with Ukraine have deteriorated, 17.7% think they have worsened significantly, and only 21.9% feel they have remained unchanged.

Support for hosting Ukrainian refugees has also declined. A CBOS poll from October 10 revealed that 53% of Poles support accepting refugees from Ukraine – the lowest level since the war began. Back in March 2022, 94% of Poles supported this.

Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawieckiand Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaks to soldiers in Warsaw against the backdrop of a Rosomak APC, April 2023 (photo: Getty Images)

On one hand, this is a natural phenomenon. At the start of the full-scale invasion, attitudes toward Ukrainians improved sharply, but now they are reverting to pre-war levels, noted Szeligowski.

"In Poland, there was a significant wave of public mobilization. Naturally, such mobilization cannot be sustained in the long term. A similar process was observed in 2004 during the Orange Revolution and in 2013–2014 during the Euromaidan," the coordinator explained.

Another reason, according to Szeligowski, lies in the political rhetoric coming from the Ukrainian government.

"This rhetoric affects not only attitudes toward Ukrainians in Poland but also perceptions of Ukraine as a whole. Polish society does not understand or accept these accusations from Ukraine," Szeligowski emphasized.

He noted that a consensus has emerged within the Polish political class on two points. First, Polish policy toward Ukraine has been largely idealistic. Second, historical issues will inevitably influence Ukraine's negotiations with the European Union.

While acknowledging factors such as perceived "ingratitude" and frustration with some refugees, Yevhen Mahda, Director of the Institute of World Policy, highlighted in a conversation with RBC-Ukraine that Ukraine as a topic tends to "unite Polish voters".

At the same time, Mahda suggested that third parties might exploit existing tensions between Ukraine and Poland. In 2015, unknown vandals damaged UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Ukraiinska povstanska armia –ed.) memorials in Poland. During the protests by Polish farmers in 2023–2024, both Ukrainian and Polish foreign ministries pointed to potential Russian involvement.

"The blockade of Ukrainian grain transport was a highly sensitive and carefully calculated moment. Not only because the Confederation (a far-right pro-Russian Polish party – ed.) engaged in it but also because many actions hinted at the interest of a third party, like Russia. Pro-Russian policies don't sell in Poland after Katyn and the 2010 Smolensk crash. But anti-Ukrainian policies – disdain for Ukrainians and the like – sell very well," Mahda concluded.

Historical issues

The primary issue currently being raised revolves around history, specifically the Volyn tragedy of 1943–1945, a series of mass killings of Polish and Ukrainian civilians in Volyn, Galicia, and the eastern territories of modern Poland. Poland's interpretation of these events is categorical, labeling them as genocide against the Polish population, while Ukraine does not agree with this characterization.

For Ukrainian society, this topic does not carry the same weight as it does in Poland, where even minor details of this history receive significant public attention.

Both former President Petro Poroshenko and current President Volodymyr Zelenskyy have tried to address Poland's concerns. In October 2020, Zelensky, during a joint interview with Polish President Andrzej Duda, declared that "issues of historical memory have been completely resolved".

Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Andrzej Duda attend the Eaglets Memorial at the Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv, January 2023 (photo: Getty Images)

However, Poland still raises concerns over how the Volyn tragedy is interpreted. In July 2023, the Polish Sejm adopted a resolution commemorating the victims of the Volyn tragedy, stating that Polish-Ukrainian reconciliation must include "an acknowledgment of guilt".

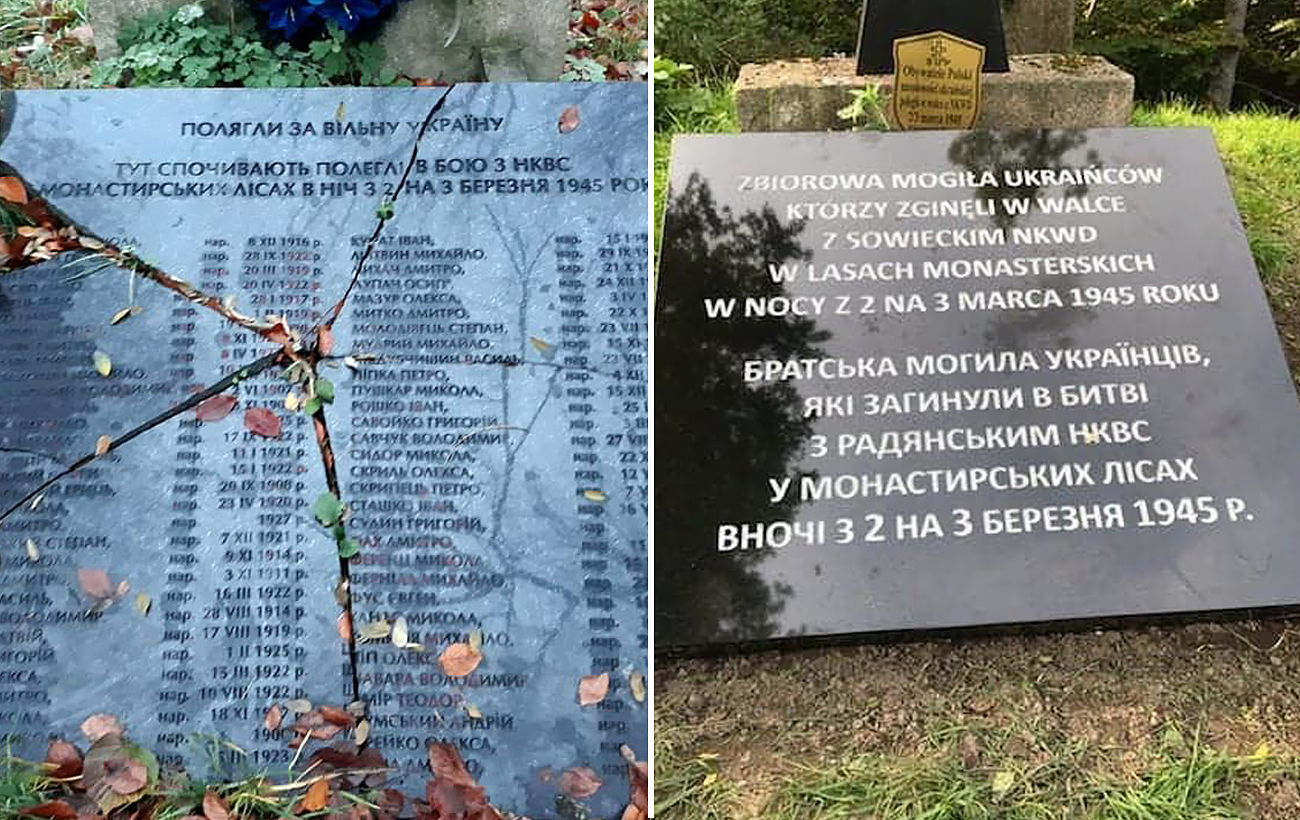

The current primary point of contention between Ukraine and Poland concerns the authorization for exhuming the graves of ethnic Poles in Ukraine. Since 2017, a moratorium has prohibited Polish institutions from searching for burial sites and exhuming the victims of the Volyn tragedy.

Ukraine's position is that this issue should be resolved based on parity and mutual respect, including equal treatment of Ukrainian graves in Poland.

One of the most contentious examples is the memorial on Monastyr Hill in Poland's Podkarpackie Voivodeship, near the Ukrainian border. The site contains the grave of 62 UPA soldiers who died fighting Soviet NKVD (Soviet secret police agency, a forerunner of the KGB forces – ed.). In 2015, vandals damaged the memorial plaque, and in 2020, they completely destroyed it. While the gravestone was later restored, it did not include the names of the fallen. Until this memorial is fully restored to its original state, Ukraine has been reluctant to grant exhumation permissions, according to Lukasz Adamski, Deputy Director of the Juliusz Mieroszewski Dialogue Center.

"The political issue is whether the rights of UPA victims or other victims in Ukraine to be buried should depend on whether states resolve the dispute over the inscription on an existing UPA grave in Poland," Adamski told RBC-Ukraine.

The Deputy Director of the Juliusz Mieroszewski Dialogue Center also added that, in contrast, there is no prohibition in Poland against the search or exhumation of Ukrainian graves.

Memorial on the Monastyr Mountain. On the left – destroyed, on the right – restored. (collage: RBC-Ukraine)

"Ukraine is using this Polish misstep (regarding the Monastyr memorial – ed.) as a pretext to block exhumations. This, in turn, stirs significant emotions in Poland and narrows the maneuvering space for any government, even the most pro-Ukrainian one," Adamski said.

On the Ukrainian side, Anton Drobovych, Head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, commented to RBC-Ukraine that the country is doing everything necessary to facilitate exhumations. He noted that the institute had received a request from a Polish citizen to conduct searches in the Rivne region, which has been included in its 2025 plan. Furthermore, Ukraine's Ministry of Culture received a request to continue work in Puzhnyky, the Ternopil region.

At various times, leaders of Polish institutions have submitted different requests, which are now being clarified.

"As for the full list of memorial sites Poland is interested in, I sent a letter to the Polish Ministry of Culture and the Polish Institute of National Memory back in September, asking them to finalize and provide this list. In November, the Polish ministry responded positively, expressing their willingness for constructive cooperation and their hope that the Polish Institute would provide the list. As of November 15, however, we have not yet received the list from the Polish Institute," Drobovych said.

Regarding the restoration of memorials, Drobovych noted constructive cooperation between the culture ministries of both countries.

"They are working on developing an effective mechanism. There is hope this will lead to constructive progress rather than an exchange of vague statements without specifics," Drobovych added.

Preserving strategic support for Ukraine

The key issue is how historical disagreements might affect more strategic cooperation between Ukraine and Poland. This is particularly important in the context of challenges stemming from Donald Trump's return to power in the United States. There remains uncertainty about his intentions to end the war, which does not necessarily imply compromising Ukraine's interests.

"In Poland, unlike Western Europe, there is no fear over Trump's return to power. Instead, there is a certain hope that he might somehow shift the situation in Ukraine's favor," emphasized Lukasz Adamski.

Adamski noted that a significant challenge would arise if Trump pursued a second Yalta Conference at Ukraine's expense. The original Yalta Conference, held in February 1945, saw the leaders of the USSR, the US, and the UK divide spheres of influence in Europe.

"Fortunately, I think we are far from such a scenario. However, if it happened, it would be a challenge for Poland, how to respond. Any agreements in the 'Yalta' style threaten not only Ukraine but also Poland, as they signal that the views of small and medium-sized states are disregarded, and the world reverts to a concert of major powers," Adamski explained.

Poland primarily defends its national interests, said expert Yevhen Mahda.

"Poland has no real alternative but to act as Ukraine's advocate. If they don't, Russia will knock directly on their door, doing so ever more persistently each time," Mahda stated.

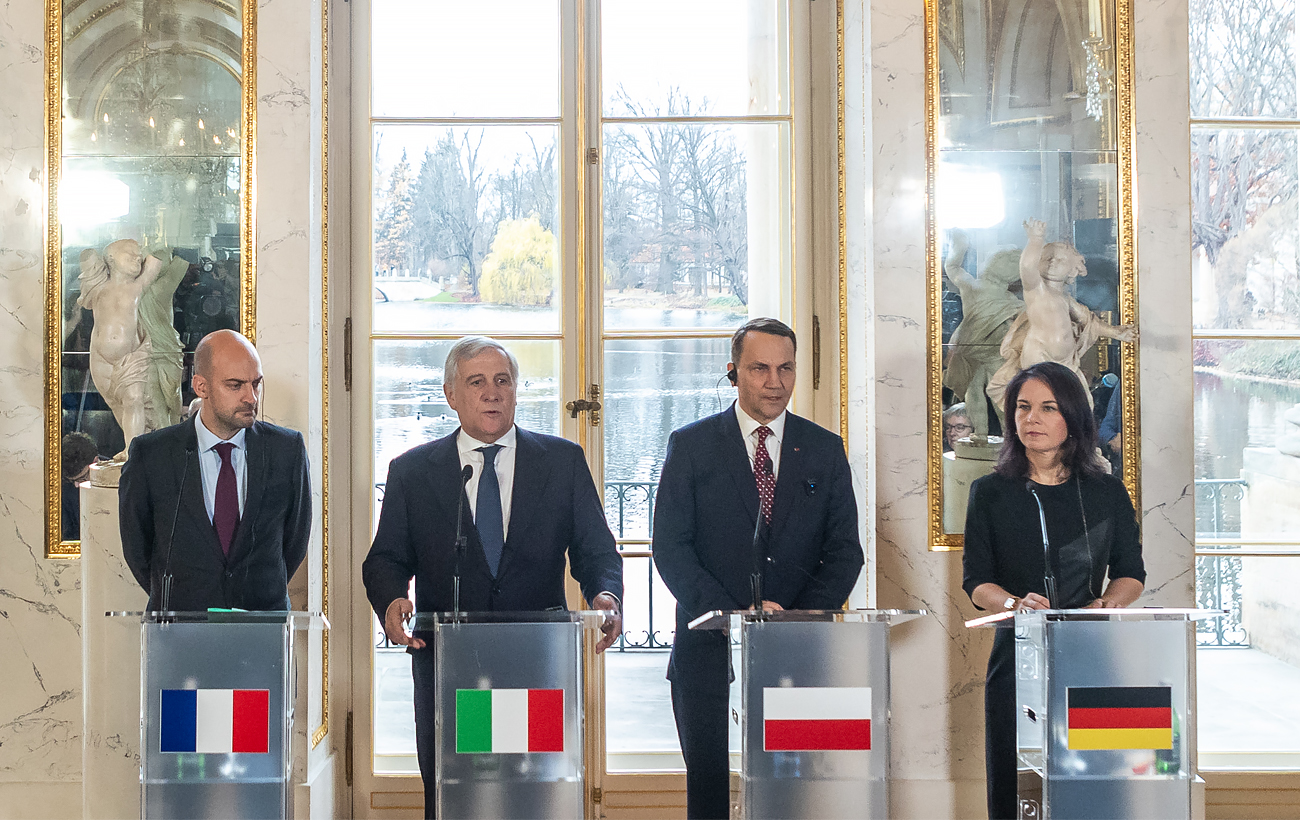

A recent example underscoring Poland's strategic role was the Weimar Triangle+ meeting in Warsaw, which brought together foreign ministers from Poland, Germany, and France, joined by representatives from Italy and the UK.

Weimar Triangle+ meeting in Warsaw (photo: Getty Images)

On the other hand, the question remains: Is Poland, along with other nations, prepared for more active measures to counter Russia? For example, neither Warsaw nor Ukraine's other neighbors have dared to intercept Russian drones crossing their airspace.

"From my personal perspective, this is one of the things that should be included in a long-term strategy crafted by Europeans. When we think about ending the war here in Ukraine, we already need to know what comes next, whether preparing for the next war or figuring out how to protect both our countries and peoples from future conflicts," told Mateusz Szymowski, a communications expert with GFT.

Another significant aspect of strategic cooperation between Kyiv and Warsaw is Poland's upcoming presidency of the European Union, beginning on January 1. Despite current rhetoric from Polish officials, experts do not foresee significant obstacles.

"At this stage, it's unlikely that Poland will create barriers to Ukraine's path toward the EU. All their official statements emphasize that Ukraine must become a member of the EU. While we will resolve all our issues, this will happen after the war. Currently, I don't see critical points that could block our accession process during the legislative screening phase (expected to last through 2025 – ed.)," said Yuliya Shaipova, an associate expert at the Ukrainian Prism Foreign Policy Council.

Shaipova also added that even with a friendly EU presidency, Ukraine must still do its "homework" on European integration.

As for bilateral Polish-Ukrainian relations, Kyiv should at least learn one lesson: it should not expect tensions to subside simply because of Poland's elections or a change in power. For its part, Warsaw should avoid artificially inflaming historical disputes and tying them to strategic contemporary issues, such as Ukraine's EU membership. Under such conditions, even if not in a "honeymoon" phase, Ukraine and Poland can weather the geopolitical storms that continue to loom on the horizon.

Sources: Statements from Polish and Ukrainian politicians, sociological surveys, and comments from Daniel Szeligowski, Lukasz Adamski, Yevhen Mahda, Anton Drobovych, Mateusz Szymowski, and Yuliia Shaipova.