Forgotten genius: Ukrainian who discovered X-rays but lost Nobel race

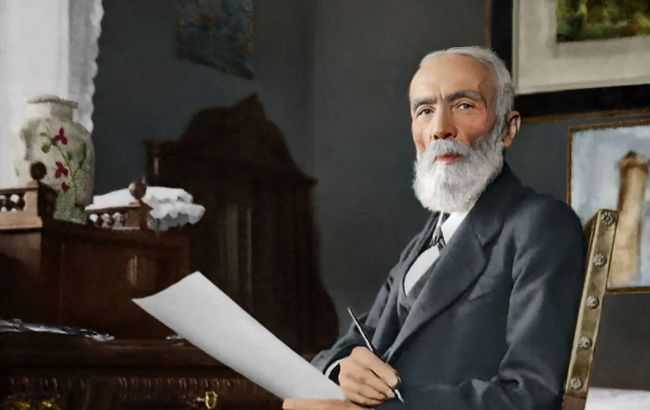

The X-ray inventor Ivan Puluj, overshadowed by Röntgen (photo: vue.gov.ua)

The X-ray inventor Ivan Puluj, overshadowed by Röntgen (photo: vue.gov.ua)

When the world first learned about X-rays, the news spread through newspapers faster than through scientific journals. Yet in the shadow of the "official" discovery stood Ukrainian physicist Ivan Puluj – a man who had already developed his own gas-discharge lamp, produced high-quality X-ray images, and explained the mechanics of the rays.

RBC-Ukraine explains why the Nobel story ended up associated with a different name – and not a Ukrainian one.

The beginning of the race: Europe on the verge of a sensation

The late 19th century was a period when physics literally sparkled with discoveries. Research on cathode rays, electricity, and vacuum tubes was underway simultaneously in laboratories across Europe. In this scientific ecosystem, dozens of researchers were working in parallel, and the question was not only who would make a discovery, but who would record it first and give it a name.

Who was Ivan Puluj, and why did he matter

Ivan Puluj was a Ukrainian physicist and electrical engineer who worked in Vienna and Prague, serving as a professor at the Prague Polytechnic. His expertise lay in gas-discharge processes and cathode rays.

He was born in 1845 in a small town in the Chortkiv district of the Ternopil region. His father was the mayor of Hrymailiv, where the future genius completed his early schooling. He then studied at the Ternopil Gymnasium, and during his school years, he and his brothers founded a secret Ukrainian youth society called Hromada.

Puluj was versatile from a young age. As a student, he translated a geometry textbook into Ukrainian, the first of its kind for Ukrainian gymnasiums. After finishing school, he entered the Greek Catholic seminary in Vienna, where he also translated spiritual literature into Ukrainian. It was there that he met Panteleimon Kulish and Nechuy-Levytsky, and together they translated the Bible into Ukrainian. Alongside these translations, Puluj attended classes in mathematics, physics, and astronomy, subjects that would capture his lifelong interest.

This passion led him to abandon the path to the priesthood and instead enroll in the philosophy faculty to continue his studies.

Between 1872 and 1874, Puluj worked as a researcher in Professor von Láng’s physics laboratory. He later became a lecturer at the Naval Academy and designed an instrument for measuring the mechanical equivalent of heat, which gained recognition in the scientific community and earned a silver medal in Paris.

From 1880 to 1882, four significant articles by Puluj on cathode rays were published in the Reports of the Vienna Academy of Sciences, making a notable impact on the physics community. His monograph on cathode ray research was published in 1889 in English by the London Physical Society as part of the Physical Memoirs series, which featured the most important physics research conducted outside Great Britain.

Puluj’s research on cathode rays paved the way for two major discoveries in classical physics: X-rays (1896) and the electron (1897).

Long before 1895, he developed his own vacuum tube, later known as the Puluj lamp, which emitted intense radiation and allowed clear imaging of internal structures of objects and the human body. Puluj was not chasing sensationalism; he systematically studied the physics of the process.

Ukrainian inventor Ivan Puluj (photo: vue.gov.ua)

November 1895: when the world heard Röntgen’s name

In November 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen publicly announced the discovery of a new type of radiation – X-rays. He quickly published his results, sent copies to colleagues, and the press instantly turned it into a global sensation.

The world received a simple, clear formula: new rays exist, there is an author, and there is a name. At this stage, a brand was established that science could no longer rewrite.

What Puluj was doing in parallel

By early 1896, Ivan Puluj had published his own work, showcasing X-ray images of exceptionally high quality and attempting to explain the mechanism behind the radiation.

His results were not secondary – they were practical and deeper from an engineering perspective. Essentially, Puluj performed what today would be called technological validation of the discovery.

Why he lost

Puluj did not lose due to a lack of talent or results, but because of:

-

The absence of the first public announcement of the discovery as a new phenomenon;

-

Weaker communication with international scientific centers;

-

Delay in the information race that Röntgen won;

-

The Nobel Committee’s logic rewards clear priority rather than parallel contributions.

In 1901, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Röntgen for the discovery of the rays named after him. The wording left no room for co-recipients.

Interestingly, Röntgen ordered his personal archive to be destroyed, including lab notes and correspondence. It is now unknown which discharge tube he used when, according to him, he accidentally discovered unknown radiation in November 1895.

In his announcement, he did not credit the tube’s inventor, mentioning only Hittorf, Crookes, and Lenard tubes. Puluj, whose designs were widely used and industrially produced in Leipzig, was not mentioned.

It is known that Röntgen and Puluj were personally acquainted – both worked in Professor Kundt’s laboratory in Strasbourg – but Röntgen never mentioned his Ukrainian colleague in his publications.

Modern scientific viewIvan Puluj is not the “official discoverer” of X-rays, but he is one of the key pioneers of radiology, making a decisive contribution to its early development and practical applications.

“There is no greater honor for an intelligent man than to preserve his personal and national dignity and work faithfully for the good of his people, even without rewards, to ensure them a better future” – Ivan Puluj.

Source: NobelPrize.org, Bukovinian State Medical University, R.P. Haida Ivan Puluj and the Development of X-ray Science