How the Holodomor reshaped Ukraine: Historian breaks down the Soviet regime's atrocities

Mykhailo Kostiv, PhD in History (Photo: RBC-Ukraine/Vitalii Nosach)

Mykhailo Kostiv, PhD in History (Photo: RBC-Ukraine/Vitalii Nosach)

Today, on November 22, Ukraine and the world honor the memory of millions of Ukrainians who became victims of the artificial mass famine of 1921-1923, the Holodomor-Genocide of 1932-1933, and the man-made mass famine of 1946-1947. RBC-Ukraine speaks with Mykhailo Kostiv, Head of the Research Department on Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes at the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, about why the 1932-1933 famine was a genocide, how the Soviet authorities organized it, how many people actually died, and why the world ignored the tragedy for so long.

Key questions:

- Three famines in half a century: How the Soviet authorities exterminated Ukrainians?

- The war for the harvest: Who was responsible for the 1932-1933 Holodomor?

- Which regions were most affected by the Holodomor, and how did Ukrainians survive?

- Death camps and depopulated villages: What's the real number of Holodomor victims?

- Appeasing evil: Why the world turned a blind eye to Soviet crimes?

- Nation's portrait after tragedy: How the Holodomor changed Ukrainians?

Over 90 years ago, Ukraine experienced one of the greatest tragedies in its history. The 1932-1933 Holodomor claimed millions of lives and permanently altered the Ukrainian nation. The famine affected all regions of Ukraine that were part of the USSR at the time. The Soviet authorities forcibly seized the last food from peasants to meet unrealistic grain procurement quotas and used hunger as a tool to subjugate Ukrainians who resisted Soviet rule.

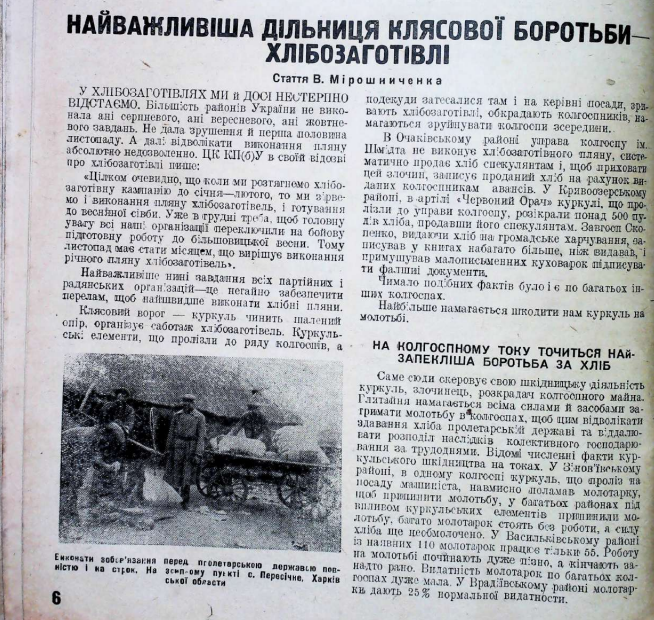

"In Communist propaganda, this was called 'the war for the harvest on the socialist front.' Contemporary media created propaganda to support this process. They wrote that Communists were 'fighting the kulaks for a better future,'" said Mykhailo Kostiv.

In Ukraine, the victims of the Holodomor are commemorated annually on the last Saturday of November. This year, the anniversary falls on November 22.

RBC-Ukraine spoke with Mykhailo Kostiv about who was truly responsible for the 1932-1933 tragedy, how many Ukrainians were killed, and why modern generations must remember this horrific crime of the USSR.

Three famines in half a century: how the Soviet authorities exterminated Ukrainians

– In the 20th century, Ukrainians experienced three devastating famines: 1921-1923, 1932-1933, and 1946-1947. What were the differences between these tragedies?

– In 1921-1923 and 1946-1947, there were mass artificial famines, while 1932-1933 was the Holodomor-genocide. The common factor in all three was the authorities' responsibility. If the government had not seized food from the population, such extreme mortality would not have occurred.

– As for the differences, in 1921-1923 and 1946-1947, the Soviet regime could partially justify its actions due to the postwar devastation. Climate factors were not decisive. Droughts were cyclical, and before the Bolsheviks, peasants prepared for them by storing food.

– A distinctive feature of the 1921-1923 famine was that the Soviet regime partially acknowledged its existence. Even then, significant campaigns collected aid for the starving, although these efforts focused more on the Volga region, despite similar famine scales in southern Ukraine.

– During 1921-1923, the Bolsheviks also allowed international food assistance. Several organizations provided aid. In contrast, in 1932-1933, the USSR denied the existence of famine, which made foreign aid impossible. The same occurred in 1946-1947.

Mykhailo Kostiv (Photo: RBC-Ukraine/Vitalii Nosach)

– Ukraine and several other countries recognize the 1932-1933 famine as the Holodomor-genocide. How exactly was Soviet policy aimed at destroying the Ukrainian nation?

– The term "genocide" was coined by Polish-American lawyer Raphael Lemkin. In the early 1950s, in his article Soviet Genocide in Ukraine, he examined the entire Stalinist policy and identified four "blows" against Ukrainians intended to destroy the nation. In his view, destruction through famine was only one component of the crime of genocide.

According to Lemkin, the first blow targeted the "brain of the nation," meaning the intelligentsia: teachers, scientists, and engineers – people capable of leading the peasantry and achieving significant intellectual and creative accomplishments.

The second element of genocide was the destruction of the church, which Lemkin metaphorically called the "soul of the nation." This refers to the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, destroyed by the USSR in the early 1930s, and, after the Soviet occupation of western Ukraine, the Greek Catholic Church. For peasants and the intelligentsia, the church was an ideological alternative: to obey Soviet orders or follow universal moral values conveyed by Christianity.

The third blow struck the "body of the nation," meaning the peasantry. In the 1920s, most Ukrainians were peasants working their own land, which was their main occupation and primary source of family sustenance. They were first forced into collective farms, and in 1932-1933, they were physically exterminated through famine.

The fourth stage of genocide involved the resettlement of people, which altered Ukraine's national composition. Depopulated villages were repopulated with people from Russia, Belarus, and other parts of the USSR, while Ukrainians were deported to northern and eastern regions of the USSR.

According to Raphael Lemkin, hunger alone does not define genocide. It was part of a broader policy of extermination, subjugation, and turning Ukrainians into obedient cogs of the Soviet system – material for building the empire.

– What were the preconditions of the Holodomor?

– The precondition for the 1932-1933 famine was collectivization, when peasants were forced to surrender all their property to collective farms and then work supposedly for their benefit. The second precondition was dekulakization. The wealthiest peasants were destroyed because, in the language of Soviet propaganda, they "exploited ordinary people."

Under this so-called economic campaign, property and land were confiscated from prosperous peasants, and they were deported to the North or simply moved outside their villages, where fertile land was scarce and farming was extremely difficult.

In reality, this was a political campaign. The label of "kulak" was often applied regardless of a peasant's actual wealth. A person could be registered as a kulak for defying authorities, opposing joining a collective farm, or protecting the church from destruction. Sometimes personal animosity from local activists was enough to place someone on the dekulakization list.

The deportations were horrific. People were herded to railway stations, where they could wait for weeks in unsuitable conditions before being transported north. Many died from these unbearable conditions. This was an entirely criminal policy.

A dekulakized family outside their home in Udachne, Donetsk region, 1930s (Photo: personal archive of Volodymyr Havshchuk / Holodomor Museum)

Dekulakization of peasant Yemets in Hryshynskyi district, Donetsk region, 1930s (Photo: Holodomor Museum archive)

– Who was the main organizer of the Holodomor?

– At the head of the state was Joseph Stalin, and he personally oversaw all the processes – we see this from archival documents. For example, the criminal intent to exterminate and use violence during the Holodomor is illustrated by correspondence between Stalin and Kaganovich regarding the "law of five ears of grain."

On August 7, 1932, the USSR issued a decree on the protection and strengthening of socialist property. It was even published in criminal code publications. According to the decree, starving peasants could be imprisoned for 10 years or even executed for cutting ears of grain in fields they had cultivated as owners just a few months earlier.

In August-September 1932, Stalin wrote to Kaganovich that this was a good law and it would work. Otherwise, control over Ukraine could be lost. These documents show that the goal of the Soviet leadership was to "tighten the screws," resulting in millions of deaths.

In addition to the organizers, there were executors who managed grain procurement locally. A plan was set for Ukraine. Each region, district, and collective farm had to deliver a certain amount of grain and other products.

The implementation of the grain procurement plan turned into a militarized campaign of violence. Grain procurement brigades often broke into homes with weapons and frequently seized all available food.

Among the main perpetrators of the Holodomor, besides those already mentioned, were Kosior, Postyshev, Chubar, Balytsky, Khatayevich, and others. Each ensured, in their area of responsibility, the creation of conditions incompatible with life.

A page from the November 30, 1932, issue of Chervone Selo magazine (Photo: Holodomor Museum archive)

– The 1932-1933 famine affected all regions of Ukraine that were part of the USSR. Which areas were hit the hardest?

– The hardest-hit regions were those long known for their fertile soil. These included Cherkasy, Kyiv, Poltava, Podillia, and Kharkiv regions. From the documents I have reviewed, the mortality from famine in some areas, such as Cherkasy and the southern part of the modern Kyiv region, was absolutely horrifying.

A similar pattern was observed in southern Ukraine, in the steppe regions. There, natural conditions made it even harder to obtain food substitutes, which again led to mass mortality. In the northern regions, in Polissia, where forests cover larger areas, famine mortality was somewhat lower. Researchers cite one reason for this difference: easier access to edible substitutes, such as acorns and chestnuts.

Population decline, 1929–1933 (Infographic: Wikipedia)

Methods of survival: how Ukrainians coped with the famine

– Eyewitness accounts tell us that during the famine, Ukrainians were forced to eat lamb's quarters, nettles, and even tree bark to survive. What other measures did they take to stay alive?

– Survival often depended on local conditions. One witness recalled that his family survived thanks to beet pulp, which they could obtain from a sugar factory.

In the Donetsk region, when people realized all their food was being confiscated, they went to cities to work for rations at industrial sites and mines.

Some tried to leave for Belarus or Russia. In 1932, this was still possible. A letter from Belarusian workers to the leadership of the Communist Party of Ukraine noted their confusion: Ukrainians had such fertile land, yet they wandered Belarusian train stations and markets trying to exchange personal belongings for food.

By January 1933, the USSR issued decrees isolating the famine zone and preventing Ukrainians from traveling to Russia, Belarus, or other countries. At that time, the border with Poland ran along the Zbruch River, and with Romania along the Dniester. These borders were tightly guarded by Soviet border troops. Nevertheless, a few people managed to escape the USSR, and some of them later became sources of information for foreign press reports on the famine.

– How widespread were cases of cannibalism?

– Research on this topic often relies on eyewitness accounts, although the Soviet system did document such cases and opened criminal investigations. The archives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine contain over a thousand cases related to cannibalism, though some cases involved multiple murders.

Nearly a thousand additional cases were destroyed in the 1950s. Archivists note a pattern: the cases that survived typically involved defendants who received long prison sentences.

Other sources also exist. For example, when cases of cannibalism were reported by district authorities to regional and then republican leadership and the Communist Party of Ukraine (Bolsheviks), they generated a kind of formal reporting. Based on a comprehensive study of these documents, researchers estimate that several thousand cases of cannibalism occurred.

– How widespread was child mortality?

– The younger the child, the higher the risk of dying during the famine. Orphanages were a major tragedy, often turning into "death camps" due to the lack of adequate provisions. Eyewitnesses recalled the Myrhorod orphanage in the Poltava region in the spring of 1933, where children went out into the yard to pull up grass just to eat. They were simply trying to survive.

Records of deaths in orphanages were likely inaccurate. In Zaporizhzhia, some children were registered under fictitious names, often after figures who supported the communist regime, both inside the Soviet Union and abroad — for example, Bernard Shaw, the Irish playwright who denied the Holodomor in Ukraine.

According to one account, deceased children in Zaporizhzhia were buried immediately near the orphanage.

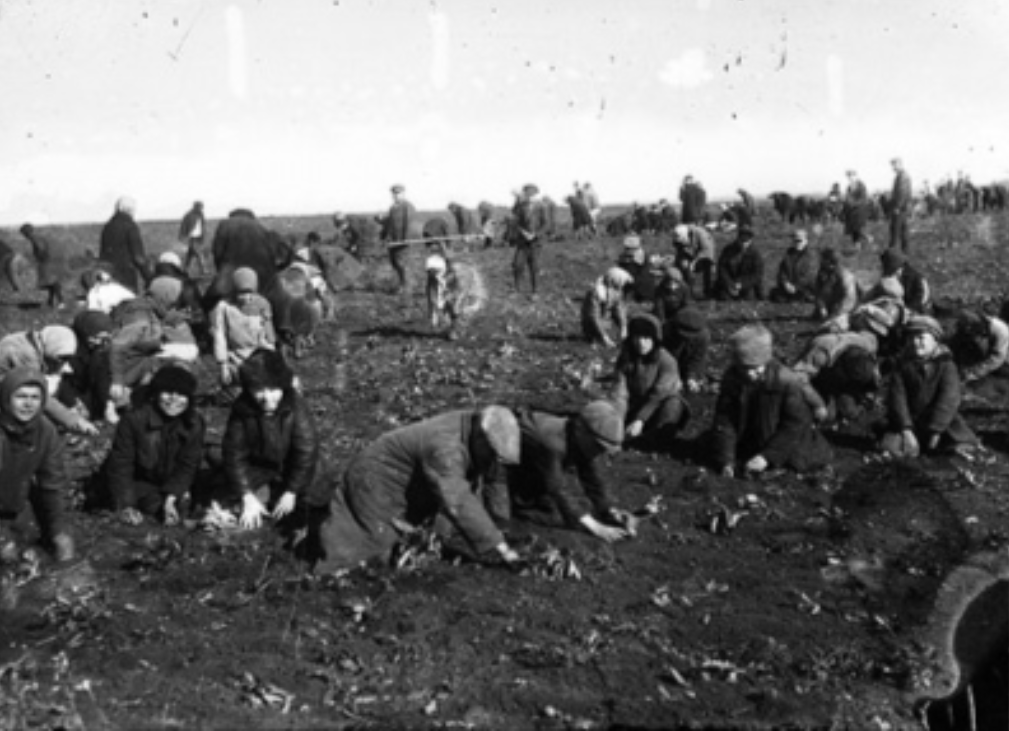

Children collecting frozen potatoes in a collective farm field in Udachne, Donetsk region, 1933 (Photo: Holodomor Museum archive)

The Holodomor peaked in June 1933, with an estimated 28,000 people dying each day under extreme conditions (Photo: Holodomor Museum archive)

– According to current estimates, how many people died in the Holodomor?

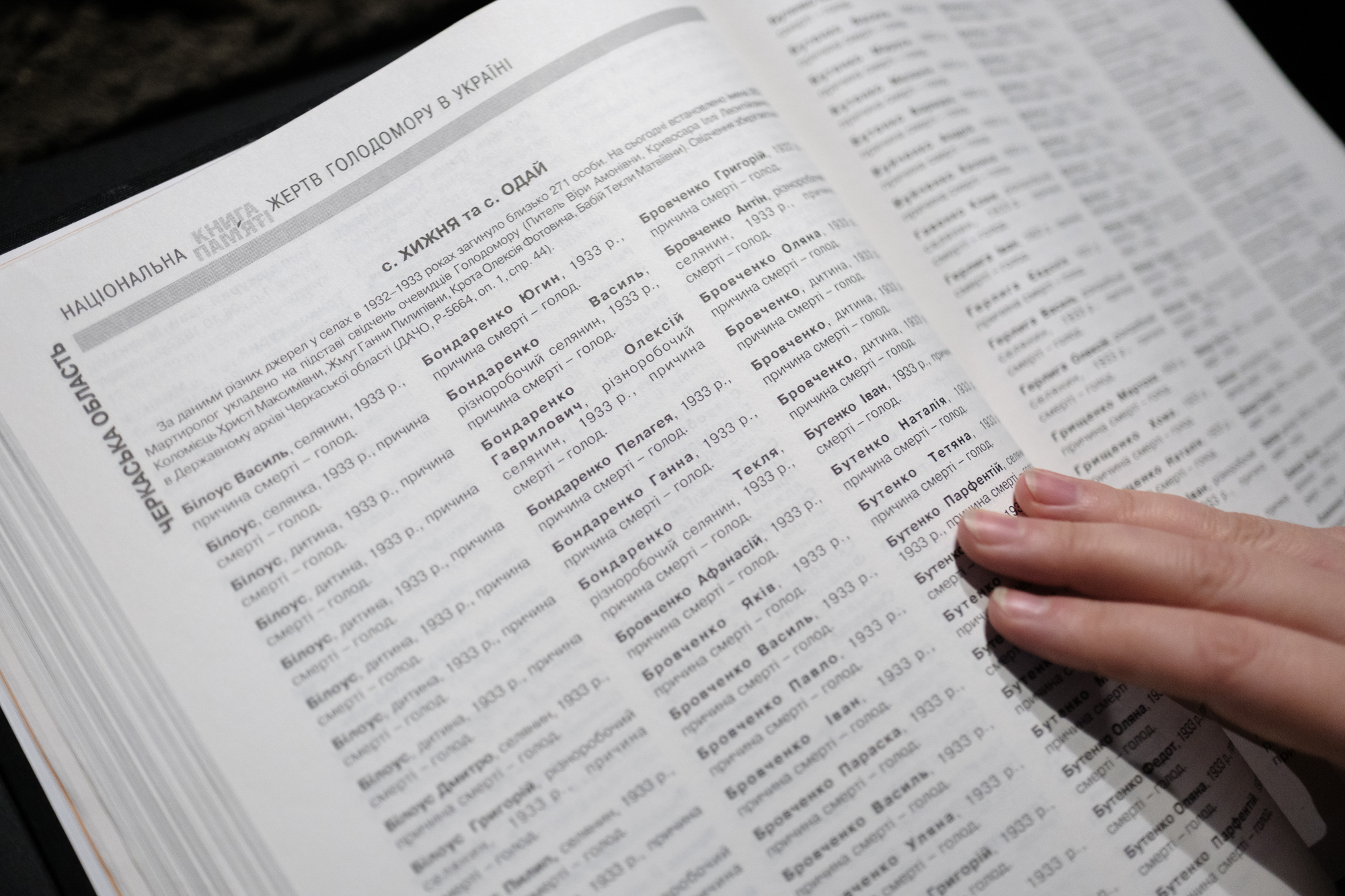

– Researchers now estimate at least 4.5 million victims, though studies are ongoing. Each death was a profound tragedy, and scholars continue working to document as many names, circumstances, and mass burial sites as possible.

Key sources include official civil registry records from rural councils and city authorities. About 900,000 records survive, though entire regions are missing due to lost data.

In 2008, then-President Viktor Yushchenko launched the National Book of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holodomor of 1932-1933, producing 19 volumes. Editorial teams compiled the materials quickly, and some continued the work in later years. In 2018, an additional volume was released for the Kharkiv region.

Eyewitness testimonies collected over decades provide further insight. People recalled relatives, neighbors, and classmates who died of starvation. They recognized the scale of the crime and sought to preserve the memory of the victims, since the Soviet state never officially acknowledged the famine.

In the late Soviet period, the first memorials to Holodomor victims began to appear, including at cemeteries. These served as “living memory,” as many still personally knew the victims and sought to honor them.

National Book of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holodomor of 1932-1933 lists approximately 900,000 victims of starvation (Photo: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

Appeasing evil: why the world turned a blind eye to Soviet crimes

– The 1932-1933 Holodomor reached catastrophic proportions. How did the Soviet authorities manage to hide it from the world?

– The issue is complex. Contemporary research shows that the famine in Ukraine was not entirely hidden abroad. While the Soviet Union insisted there was no famine, newspapers in the United Kingdom, the US, France, and other countries reported mass deaths from starvation.

A review of the 1932-1933 foreign press reveals extensive coverage of the Holodomor. The famine was widely known in Western countries.

– Did anyone attempt to aid Ukrainians?

– Initial efforts to help the starving and publicize the famine came from civic groups in Western Ukrainian territories, then under Polish and Romanian control. Upon receiving reports of the famine, these groups established relief committees.

The committees distributed information about the Holodomor and collected food donations. The Soviet Union, however, denied the famine and refused foreign assistance. Only a few individuals could send parcels privately via Torgsin stores (from the Russian "torgovlya s inostrantsami" – trade with foreigners), typically those with relatives abroad maintaining correspondence.

Activists such as Milena Rudnytska attempted to raise the issue at the League of Nations, the main international body at the time, but no measures were adopted to halt the famine.

Norwegian politician Johan Ludwig Mowinckel also tried to provide assistance. Despite his standing in European political circles, he was unsuccessful. The effort was supported by Vienna Archbishop Theodor Innitzer and German civic activist Ewald Ammende, who published one of the first books on the Holodomor in 1935.

Ammende reported in the Austrian press that millions were dying of starvation in Ukraine. The Soviet Union responded by accusing German and Austrian "fascists" of spreading falsehoods and claimed instead that Austrian workers lived in hardship, consuming dogs and cats.

Mykhailo Kostiv: "Contemporary research shows that sufficient information about the Holodomor was available abroad" (Photo: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

– Articles about the famine in Ukraine appeared in the American press. Why did the US fail to recognize the Holodomor at the time?

– Ukrainian Americans organized mass demonstrations to draw attention to the famine affecting their compatriots in the USSR. Congressman Hamilton Fish Jr. raised the issue in the House of Representatives and drafted a resolution addressing the crisis.

However, this coincided with the US establishing formal diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in the fall of 1933. As a result, some Ukrainian Americans criticized President Franklin Delano Roosevelt for prioritizing cooperation with Moscow over addressing the humanitarian disaster.

Nation's portrait after tragedy: how the Holodomor changed Ukrainians

– Tragedies of this scale leave enduring effects. How did the Holodomor transform the nation?

– The famine increased Ukrainians' subservience to authority, offering a stark lesson: disobedience could provoke violence, including food confiscation or repression. Many even feared telling their children and grandchildren about the famine.

It fostered the belief that individuals had no control and could not influence events. Opposing authority carried a high risk of punishment. Survival required blending into the masses.

– Did the Soviet authorities succeed in turning people into cogs of the system?

– Partly, yes. Many complied with Soviet directives. However, 20th-century Ukrainian history also shows that numerous independence fighters survived the Holodomor. Levko Lukianenko recalled that his family in Chernihiv survived by burying potatoes along a path, which grain-collection brigades failed to find.

This example shows that some consciously resisted the Soviet system and later opposed Russia's imperial policies. Many Ukrainians refused to become mere cogs in the machinery.

– Russia still has not recognized the Holodomor or expressed any remorse…

– They not only lack repentance. On the contrary, they continue to aggressively deny these events. A clear example is the destruction of Holodomor memorials in occupied territories, including Mariupol, Luhansk, and Kherson. This shows that Russians fail to acknowledge their past wrongs.

Instead of addressing domestic societal issues, the Russian leadership focuses on violence, destruction, and devastation. This path will yield no positive outcomes, as it deforms their society.

Ukraine observes the Holodomor victims annually on the last Saturday of November (Photo: Getty Images)

– What helps Ukrainians grasp the Holodomor tragedy?

– Understanding it is essential. A key reason the Holodomor occurred was that Ukrainians lacked an independent state. Criminal orders to destroy Ukrainians were issued directly from Moscow. When a foreign occupying power can fully control a country, the worst outcomes become inevitable.

Parallels with the current war show that such orders still come from the same centers of power, reflecting ongoing forms of genocide. On an individual level, the killing of farmer Oleksandr Hordienko echoes the Holodomor. He sought to farm his own land, yet Russian forces killed him. Hordienko personally cleared mines in Kherson and died in September 2025 from a Russian drone strike. This illustrates the continuity of destructive policies from the Russian Empire and Soviet Union to modern Russia.