80 years on: Why Ukraine and Poland remain divided over the Volhynia massacre

Historians Mariusz Zajączkowski and Roman Kabachiy (photo: RBC-Ukraine collage)

Historians Mariusz Zajączkowski and Roman Kabachiy (photo: RBC-Ukraine collage)

Ukrainian historian Roman Kabachiy and Polish historian Mariusz Zajączkowski tell RBC-Ukraine how the Volhynia tragedy still divides Poles and Ukrainians, what actually happened between the two peoples 80 years ago, and whether they can find a common understanding.

Takeaways

- Will the beginning of exhumations in Puzhnyky become a breakthrough in Ukrainian-Polish relations?

- Why do Poles pay significantly more attention to the events in Volhynia than Ukrainians?

- How do politicians exploit the topic of the Polish-Ukrainian conflict?

- Is a shared historical truth between Poles and Ukrainians about the Volhynia tragedy possible?

This week the exhumation of Poles – victims of the Volhynia tragedy – beganin the south of the Ternopil region. The site of the work is the now non-existent village of Puzhnyky, one of the centers of Polish underground activity, where in February 1945, over 80 Poles of various ages and genders were killed by Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) fighters.

It should not be surprising that the tragedy (or, in the Polish version, the massacre) happened in Volhynia (Volyn), while excavations are taking place in Galicia – the long-standing Polish-Ukrainian ethnic conflict had spread practically across all territories where representatives of both peoples lived side by side.

Those events still remain on the agenda of Polish-Ukrainian relations, even despite seemingly more pressing issues (at least from the Ukrainian point of view) such as countering Russian aggression.

In Poland, unlike in Ukraine, the topic of the tragedy and related events receives much greater public attention than in Ukraine. And of course, it is regularly exploited by various far-right Polish politicians, especially during election campaigns.

Even the start of exhumation work in Puzhnyky coincided with another incident – at the mass grave of UPA soldiers on Monastyr Hill in Poland, unknown installed a plaque with a provocative inscription. "It is clear that some people do not want constructive dialogue. They want conflicts between Ukraine and Poland," commented the spokesperson of the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Heorhii Tykhyi.

However, even more mainstream politicians, such as Poland's Minister of Defense Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, publicly link, for instance, Ukraine's further European integration with the "resolution of the Volhynia issue."

Therefore, one should not expect that after the end of the current presidential campaign in Poland, the topic of those events will fade into the margins of public attention – on the contrary, it will remain on the agenda for a long time. But in any case, excessive emotions and a black-and-white worldview, which often manifests itself both in Kyiv and Warsaw, definitely harm both digging up historical truth and – more importantly – the present and future of Polish-Ukrainian relations.

More about the topic – in an interview with Roman Kabachiy, senior researcher at the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War, Candidate of Historical Sciences, and Mariusz Zajączkowski, Polish historian, political scientist, associate professor at the Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Doctor of Sciences.

_1.jpg)

Roman Kabachiy: 'For some reason, Poles think that the red-and-black flag is solely an anti-Polish flag.'

– Can we call the beginning of the excavations in Puzhnyky a breakthrough in the long-standing history of disputes between Ukrainians and Poles on the events of 80 years ago? And is this the first such exhumation of Poles in Ukraine?

– No, this is not the first exhumation. The largest exhumations were conducted in the Liuboml district at the sites of the villages of Volya Ostrovetska and Ostrivky in 2011, ahead of the joint Euro-2012.

– And then there was a long pause in these works?

– The pause occurred because, most likely, the Ukrainian authorities wanted to limit themselves to symbolic gestures. For example, the unveiling of the monument in Pavlivka, formerly Porytsk, by former presidents Kuchma and Kwaśniewski, then former president Poroshenko kneeling before the monument to the victims of the Volhynia tragedy in Warsaw, and a joint prayer by Presidents Duda and Zelenskyy in Lutsk.

And evidently, the Ukrainian side wanted to believe that such symbolic gestures of reconciliation would be sufficient. Meanwhile, the Polish side demanded, if not apologies from the Verkhovna Rada for the actions of a particular party, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, and its military formation, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. Then they began using it with a political undertone. They stated that there should be no grave without a cross, without a candle, and so on, that the remains of thousands of Poles were scattered, etc.

Although it is unlikely that mass exhumations will be possible for many reasons, I believe that symbolic steps must be taken. Puzhnyky came to light because in 2023 search works were already being conducted there, meaning that throughout the summer, Ukrainian and Polish archaeologists were searching for a mass grave in this village, which no longer exists and is now overgrown with forest. By the end of summer, even by fall, they found it and, accordingly, preserved it until further permits were granted.

Our state is very bureaucratic, and all these permits must be reapplied for every year. It seems that last year this cycle of permits was not completed, but it was decided that excavation could already begin this year. And most likely, after the change of our Minister of Culture, there was progress in resolving this issue. A commission was created consisting of two representatives from our Ministry of Culture and the Institute of National Remembrance and two Polish representatives. And it approves the lists of what exactly will be excavated.

There is also the issue that the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, even under Drobovych and earlier under Viatrovych, made a condition of the restoration of the monument on Monastery hill in Poland, where UPA fighters died in battle with the NKVD on March 3, 1945. A tombstone was placed by the Polish authorities, with the names of the fallen UPA soldiers and an inscription "They died for the freedom of Ukraine." However, when vandals destroyed this stone, under Duda, the inscription was restored — but without the names.

I understand that our ministry and the Institute of National Remembrance are hoping for the noble behavior of the Poles, so we have already permitted the continuation of exhumation — not search — works.

– Why do they start excavating in the south of the Ternopil region if the Volhynia tragedy is always mentioned?

– Overall, in Polish consciousness, the largest number of Poles killed during the Polish-Ukrainian ethnic conflict was on the territory of the former Volhynian Voivodeship, which included the present-day Volyn region, Rivne region, and northern Ternopil region. However, after 1943, the conflict spread to Eastern Galicia and also to the Zakerzonia region.

And, in fact, the killing in Puzhnyky happened in February 1945. At the beginning of spring 1945, the largest killings of Ukrainians on the other side of the border occurred, in Nadsanie — Pawłokoma, Novyi and Staryi Lubliniec, Piskorowice, Horayets. On one side, where there were fewer Poles, our side attacked, for certain reasons.

It is believed that Puzhnyky was a Polish village where the Home Army operated until the Soviets came. Then these young men actually transitioned into "destruction battalions." The Home Army was officially disbanded at the beginning of 1945, and they had to do something, so they tried to defend their villages this way.

– Am I correct that at that moment, these former Home Army soldiers were under the command of the NKVD?

– Yes, it was a kind of self-defense used by the Soviets.

Of course, it sounds odd that Volhynian exhumations are being conducted in the south of the Ternopil region — but it's all one large ethnic conflict. It began in Volhynia and then spread over this vast territory.

– Why do Polish society and media pay disproportionately more attention to these events than Ukrainian ones, even though it was a confrontation between both nations? Why is there such a clear imbalance?

– There is an imbalance because those who survived then moved to Poland. These were Poles who lived in the territories of today’s five Ukrainian regions: Volyn, Rivne, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Lviv. Former Polish citizens moved to Poland under the population exchange that took place precisely at the time when the killing in Puzhnyky happened (which was actually a way of intimidation). Similarly, the Polish underground pushed Ukrainians to move to the Ukrainian SSR through murders and attacks.

Now there is a lobby made up of descendants of those who moved. They are trying to pressure the state, many of them are in the Polish Sejm, and they actively push this issue.

Against the backdrop of growing negative attitudes toward Ukrainian refugees and Ukrainians who "allow" themselves to sit in restaurants, drive expensive cars, etc., it is all amplified by saying that, supposedly, they came here, while their state does not recognize this crime, does not allow exhumation, etc.

By the way, as it was in the case of Puzhnyky. Former Deputy Minister Michał Dworczyk was associated with the Freedom and Democracy foundation, whose vice-president was Maciej Dancewicz — his family was killed in Puzhnyky.

So here we are talking about a specific village that interested a specific person with appropriate capabilities and status, who was able to influence certain processes. They chose this one place so that it would later become emblematic.

Moreover, in the list presented as the deceased, the descendants of Puzhnyky residents count 88 people, and among those they list as victims, there are many women and children. So this was not a random choice either.

Residents of the village of Puzhnyky (photo: puzniki.pl)

– To what extent is this topic raised naturally, through the Poles’ desire to find out what happened to their ancestors, and to what extent is it artificially escalated by politicians for their own purposes?

– Even Polish historians admit that the instrumentalization of this issue exists. At a recent conference in Kyiv, Polish professor Grzegorz Motyka said that Ukrainians should understand that the cult of the dead in Poland is very strong. Not only on All Saints’ Day, November 1–2, candles are placed, but you can go at Christmas, at Easter, and see that these candles are there, that there is a cemetery culture in Poland. And, supposedly, these people, families imagine that somewhere out there far away, the remains of their relatives have lain for 80 years without proper burial, so something must be done about it.

Another question is that there is a part of people, descendants of those families, who say that they do not want the remains of their families to be disturbed.

Karolina Romanowska, who created the society for Ukrainian-Polish reconciliation, says she has 18 deceased members of her family in the village of Uhly in the Rivne region. She advocates for their exhumation. She says she understands that there is the present and that Ukrainians must oppose Russia, Putin together, but there must also be goodwill for other matters.

– How loudly does the topic of Volhynia sound during the current election campaign in Poland?

– In recent weeks, they have talked about it less. But Karol Nawrocki, for example, as the acting head of the Institute of National Remembrance, in December, when he was just nominated as a candidate, said "Let Ukraine give permission, I will go digging tomorrow." This is a populist approach, he really instrumentalizes this issue.

– Is it possible to achieve Ukrainian-Polish understanding regarding those events, the common historical truth, or will each side remain with its own view?

– It is unlikely to be reduced to a common denominator. Another thing is that it is necessary to talk and publish. I personally translated at the request of our Institute of National Remembrance about ten papers by Polish historians, which were delivered at closed meetings of both institutes, but with the outbreak of the war, this matter was shelved. And it should have been published in both languages, so that Ukrainians could read the arguments and evidence of the Polish side, while Poles could read the arguments and evidence of the Ukrainian side.

But I think that each will remain with their own vision because the Polish side believes that it was an anti-Polish ethnic cleansing by orders of Dmytro Klyachkivsky, for whom we have monuments, and others. Meanwhile, Poles do not want to see what led to such approaches.

Poland is outraged that, allegedly, for denying the role and contribution of the OUN and UPA in the fight for Ukrainian independence, according to one of our decommunization laws, criminal liability is provided (which is not actually written anywhere because, apparently, it was not transferred into any code). But they wave this bogeyman and shout "I am afraid to come to you because if I say that the UPA are criminals, I will be imprisoned."

Meanwhile, we on our side cannot accuse the entire Ukrainian Insurgent Army of being engaged only in Polish cleansings. They were primarily fighting the NKVD and the Nazis.

For Poles, somehow it seems that the red-and-black flag is only an anti-Polish flag, that President Zelenskyy does not shy away from being photographed against the red-and-black flag, and this is "the flag of criminals." They do not realize that it is now the flag of Ukraine, which is fighting, symbolizing blood and soil.

– Are there also burials of Ukrainians who were similarly killed during the Polish-Ukrainian conflict, the same mass graves on the territory of present-day Poland?

– Yes, there are, for example, Hrubieszów County, Tomaszów County, where about 50 villages were burned down. Polish historiography speaks of "retaliatory actions," when entire villages were killed.

The most famous in the Chełm region is Sahryń. There is a monument at the cemetery, but no exhumations have been carried out. Although ithe number of victims only in Sahryń is around 600–800 people.

– And why then has Ukraine not raised this issue also?

– The question here is that the money for the exhumations of Poles is provided by the Polish state. Has the Ukrainian state tried to provide money?

Another issue is that 17 monuments in various places in Poland were destroyed. In Hruszowice at the cemetery, where there was a monument with a trident, Poles said there were no Ukrainians here, no UPA members, no trident would be here, and they actually did not allow a proper exhumation, leveled everything with the ground. But there are many mass graves.

– Can we expect that after Puzhnyky large-scale exhumations will begin in other places? But considering the territories, hundreds of former Polish villages, it is probably impossible even theoretically to complete this history entirely.

– The point is that during the war it is also logistically difficult for the Ukrainian state to control this matter. And after the war – if this process is orderly and calm, then why not? But I do not believe that five regions will be dug up.

Mariusz Zajączkowski: 'Politicians who profit from trauma and the bones of the deceased only disrespect the memory of the conflict’s victims.'

Mariusz Zajączkowski: 'Politicians who profit from trauma and the bones of the deceased only disrespect the memory of the conflict’s victims.'

– How important is the beginning of the exhumation of the victims in the anti-Polish campaign in Puzhnyky? Can we call it a breakthrough?

– One can say so about what has happened starting from November 2024: from the declaration by the foreign ministers of Poland and Ukraine, the establishment of the Polish-Ukrainian working group on historical dialogue at the ministries of culture of both countries, and up to the beginning of exhumation works in Puzhnyky. As I assume, such works will also begin soon in other locations in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia that suffered from the anti-Polish campaign of the OUN-B and UPA in 1943–1945.

Puzhnyky is an important variable, a turning point because, after a long pause, permission for exhumation was finally obtained. Already in 2023, the Freedom and Democracy Foundation received a separate permit to search in Puzhnyky for the site of an unnamed mass grave of about a hundred Poles murdered there by the UPA in February 1945.

From spring 2017 until fall 2024, there was a lack of willingness for understanding, goodwill, as well as competence, and decisiveness on both sides — the Polish and the Ukrainian — primarily among officials of the Institute of National Remembrance in Warsaw and the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance in Kyiv, to solve the problem, which was exacerbated over the years due to the Ukrainian moratorium on search, exhumation, and proper commemoration of victims in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, including victims of the Polish-Ukrainian conflict of the 1940s.

Instead of solving the problem, both state institutions became embroiled in a dispute over the interpretation of history. They also succumbed to manipulation by circles that did not hide their sympathies toward Russia. Circles that are not interested in constructive Polish-Ukrainian dialogue or settling mutual grievances and dignified commemoration of all conflict victims, but only in further fueling hostility and spreading disinformation about historical facts.

Frankly speaking, the Polish and Ukrainian sides allowed themselves to be drawn into Russian provocations, starting from mid-2015, with a particular escalation in 2017. I mean the process of destroying and desecrating Ukrainian monuments — graves of UPA soldiers and symbolic monuments in Poland, both legal (for example, in Monastery Hill or Pikulice) and unauthorized (for example, in Hruszowice). As well as Polish monuments in Ukraine, related both to victims of the Polish-Ukrainian conflict (Pidkamin, Huta Pieniacka) and victims of Stalinist repressions (Bykivnia).

The most extreme incident was the grenade launcher attack on the building of the Polish Consulate General in Lutsk in the spring of 2017. These were not accidental actions but provoked and possibly financed by Russian special services. Pro-Russian extremists from nationalist and national Bolshevik circles took part in these actions.

Shortly thereafter, Ukraine decided on the moratorium, and in the fall of 2017, the historical dialogue that had been conducted since the second half of 2015 under the Polish-Ukrainian forum of historians was frozen. In the following years, both sides did not show a willingness for mutual understanding and appropriate will to solve the problem, accusing each other of starting the situation and escalating bilateral relations.

As I have already mentioned, Puzhnyky will not be the only site of work for Polish-Ukrainian teams of archaeologists, anthropologists, and observers from state institutions of both countries, because the task of the working group is to simplify procedures and start search and research work in places indicated in all applications submitted by the end of 2024, from both the Polish and the Ukrainian sides. The latter concerns the search for Ukrainian victims of the conflict on Polish territory.

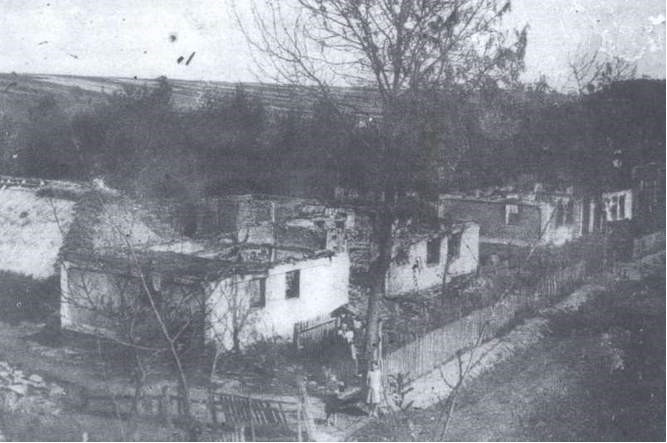

The burned village of Puznyky (photo: puzniki.pl)

– Poland pays much greater attention to history in general, and particularly to the history of the 20th century, and specifically to the events in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia during World War II, than in Ukraine. What is the reason?

– Yes, that is correct. What happened in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia in 1943–1945 to the Polish population as a result of the anti-Polish action by the OUN-B and UPA remains an unprocessed trauma for many generations, for a large part of Polish society, especially for the descendants of victims buried in anonymous mass graves.

It is one of the greatest crimes of World War II against the Polish people, comparable to the German mass murders of residents of Warsaw's Wola district during the 1944 uprising, or crimes committed by the Germans and the Soviet authorities in 1940 against the Polish elite (Palmiry, Katyn).

The memory of the Volhynian-Galician massacre is particularly painful for Poles because it became the culmination of an internal conflict between citizens of one state (the Second Polish Republic), which unfolded in its southeastern lands occupied by the Germans. In Volhynia and Eastern Galicia of 1943–1945, there was no partisan war between the Home Army and the UPA, as it is sometimes presented.

The scales of crimes and the intentions of their perpetrators were different. There were no symmetrical crimes against civilians on both sides. According to estimates, about 80,000–100,000 Poles were killed by Ukrainian hands, while about 15,000–20,000 Ukrainians died at Polish hands.

It is hard to call a war the mass killings of unarmed Polish civilians in Volhynia, including the elderly, women, and children. As well as the plundering of property, the burning of entire villages and hamlets, and the forcing of survivors to flee — all carried out by UPA units with parts of the local Ukrainian peasantry. Even though in response to these threats centers of self-defense and a few Home Army units emerged, their practically impossible mission was to defend the Polish population.

The Ukrainians, who made up the majority in those territories, suffered from the Polish reaction, which consisted of targeted strikes and crimes against civilians based on the principle of collective responsibility. This was most painfully evident not in Volhynia or Galicia, but in southeastern Lublin region in the spring of 1944. In most cases, those targeted were not the direct perpetrators of Polish suffering but innocent Ukrainian civilians, among whom were also the elderly, women, and children.

The false hypothesis is that the mass crimes in Volhynia in 1943 were inspired by Soviet authorities, initiated by the so-called first UPA — the Petliura partisans of Taras Bulba Borovets — or committed by anarchized Ukrainian peasantry independent of OUN(b) and UPA. It was supposedly susceptible to Soviet influence and carrying out a popular uprising in the first half of 1943 to bring justice to Polish peasants and not to lords or military settlers (as the latter had been liquidated by Soviet authorities during the first occupation of these lands from fall 1939 to spring 1941).

Such a version is nothing more than an attempt to blur responsibility and to justify, against the facts, the real perpetrators of mass crimes, as well as an attempt to relativize them. Responsibility for these crimes committed from February 1943 to May 1945 in Volhynia, and later in Eastern Galicia and southeastern Lublin region, lies exclusively with the Banderite wing of the Ukrainian nationalist underground.

Another important factor is that the topic of crimes in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia during the German occupation and later on Sovietized lands was taboo during the times of the Polish People's Republic. Just as the topic of Operation Vistula of 1947 against Ukrainian and Lemkos in postwar Poland. Only after 1989 could the descendants of the victims gradually begin to speak openly about their experiences, break the taboo, and express the pain and bitterness accumulated over decades.

– Is the topic of Volhynia 1943 being used in the current presidential campaign in Poland and generally in Polish politics, and if so, how strongly?

– The issue of Polish-Ukrainian relations in the 20th century still evokes numerous emotions, disputes, and controversies. Unfortunately, for many years it has been used to build political capital by individuals from politics, mainly from the far-right camp, including fascist-leaning and national-Bolshevik circles that openly demonstrate Ukrainophobia and pro-Russian sympathies, as well as circles with communist, PZPR roots (PZPR – Polish United Workers’ Party, ruling in Poland from 1948 to 1989 - ed.).

I believe that during the presidential campaign, the topic of Volhynia 1943 will not be cynically exploited. Particularly the issue of searches and exhumations, which after many years of stagnation have finally started to move forward — thanks to a departure from fruitless disputes over the interpretation of shared history and a transition to a Christian approach with due respect to all victims of the national conflict without exception.

Politicians who profit from unresolved intergenerational trauma and the bones of the dead only disrespect the memory of the victims of the conflict. The descendants of the Volhynia victims are actually waiting only for one thing: to finally be able to go to the graves of their loved ones, erect a cross there, light a candle, and pray for them. Politicians should not obstruct them but, on the contrary, do everything to make these aspirations a reality.

Memorial in Puznyky (photo: puzniki.pl)

– Will Ukraine and Poland ever be able to develop a common approach to their difficult past and the narration of it? To the events more than 80 years ago that so deeply divided Poles and Ukrainians? Or will each nation stick to its own interpretation and evaluation of those events?

– The desire to bring closer the versions of the history of two peoples who were enemies and waged a bloody conflict in the recent past is a very difficult task. I do not know whether it is achievable at all.

However, one thing is indisputable and not subject to discussion: historical facts cannot be changed, just as history itself cannot be changed. Of course, facts can be interpreted differently, each from their own perspective. But if the commission of a crime is an undisputed fact, one cannot say that it did not happen. And if it is known that a specific crime was committed by a certain perpetrator, one cannot pretend that it was someone else.

Regarding this national conflict, there are mainly two perspectives — the Polish and the Ukrainian. Often, far-reaching conclusions are drawn based solely or almost solely on one-sided national narratives.

The historian’s duty when dealing with the Polish-Ukrainian conflict during World War II is to juxtapose as many sources as possible from various origins (not only Polish and Ukrainian but also German, Soviet, Slovak, Hungarian), to compare them and critically analyze them.

Only on this basis is it possible to recreate and approach, as closely as possible, the most objective image of the past. Otherwise, the conclusions will be largely flawed, as they will not take into account the entire complexity and multidimensionality of what happened between Poles and Ukrainians in the 1940s. And much evil happened then.

It is time to get rid of the demons of the past and with due dignity and calm honor all the victims of the conflict, regardless of their nationality, faith, or worldview. They simply deserve it, all the more because the overwhelming majority of them were innocent victims.