Moldova on edge as Sandu battles to stop pro-Russian takeover in elections

Maia Sandu, President of Moldova (photo: Getty Images)

Maia Sandu, President of Moldova (photo: Getty Images)

This Sunday, September 28, Moldova will hold parliamentary elections. How President Maia Sandu's party plans to preserve the pro-European course, how Russia hopes to stage a comeback, and who has the better chances of success – read in the report by RBC-Ukraine.

Key questions:

-

Why cannot Maia Sandu's party secure a parliamentary majority on its own?

-

What strategy is Russia pursuing in Moldova’s elections?

-

Why can neither side fully predict the outcome?

Poland, Romania, Moldova. This year, a number of Ukraine's neighbors are facing fateful votes that could dramatically reshape their position in the region – and their stance toward Ukraine.

Against this backdrop, Moldova's parliamentary elections are particularly crucial for Kyiv. Part of Ukraine's exports pass through Moldovan territory, and both Kyiv and Chișinău are jointly moving toward EU membership. If one country's progress stalls, it will inevitably slow negotiations for the other.

Unlike most of Ukraine's other partners, Moldova is neither an EU nor NATO member, leaving open the risk of anti-Ukrainian moves. The unresolved issue of Transnistria, wedged between Ukraine and Moldova and under Russian influence, further complicates the picture.

This year, the stakes in Moldova are higher than ever. On September 22, President Sandu openly warned that if pro-Russian forces win the elections, her country could become a springboard for a Russian military invasion of Ukraine's Odesa region.

"Today, with utmost seriousness, I tell you: our sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity, and European future are in danger," Sandu declared.

Although she managed to win re-election last year, Moldova is a parliamentary republic, meaning real power lies with parliament and the cabinet of ministers. Until now, there had been no conflict between the president and the government, since Sandu's Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) held a parliamentary majority.

But on September 28, Moldova could follow the Georgian scenario: the head of state remains a pro-European leader – Maia Sandu herself – while the government is formed by Kremlin-backed forces.

One man is no man

Maia Sandu's party remains one of the frontrunners in the election race. According to an iData poll, it is neck-and-neck for first place with the pro-Russian Patriotic Bloc, with 24.7% and 24.9% of voters respectively. PAS is focused primarily on Moldova's pro-European citizens.

"For these voters, Europe signals better jobs, rule of law reforms, and infrastructure. Per national polling that finds high and growing trust in the EU and a desire for EU-backed anticorruption and development programs. Migration links (study/work in the EU) and daily exposure to EU institutions/media reinforce these preferences," Romanian foreign policy expert Mihai Isac told RBC-Ukraine.

Yet despite obvious achievements on the path to European integration, PAS cannot pull off a solo majority in parliament.

"A ruling party that, over four years, failed to deliver on promises like fighting corruption or raising living standards — and in fact did the opposite. Corruption hasn’t been defeated, no real legal reforms have been implemented… And for this, people blame PAS, which is now in power,” former director of Moldova’s Military Intelligence Agency Yuriy Brichag previously explained.

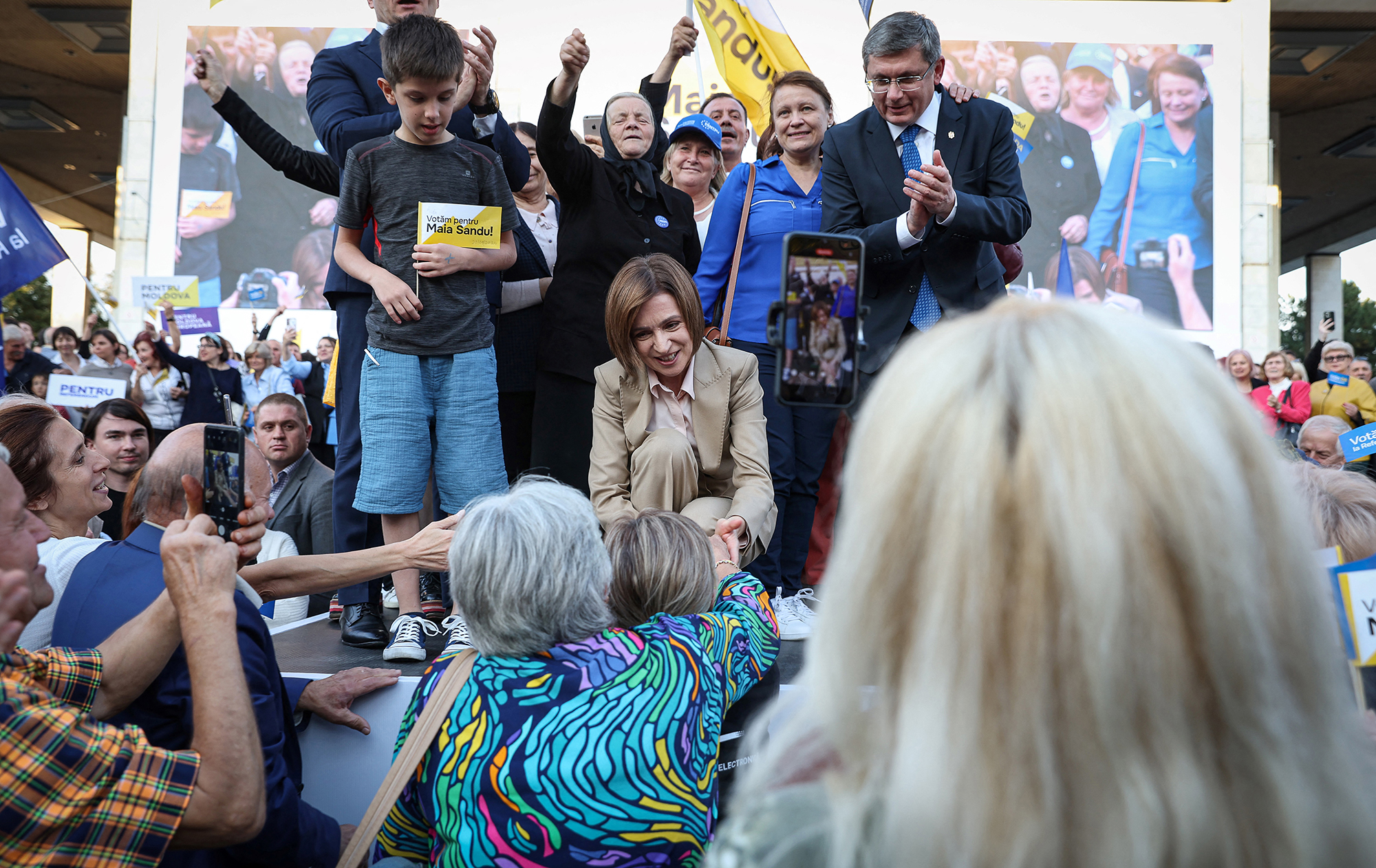

Maia Sandu at a rally, 2024 (Photo: Getty Images)

With Moldova at a crossroads, the only way forward seems to be finding a junior partner for a future coalition. For now, the only potential candidate is the populist Our Party, polling at 5.4%. Its leader, Renato Usatîi, has a track record of political flexibility and has cooperated with both pro-European and pro-Russian forces.

The problem, however, is that Our Party may simply not have enough votes. At the same time, there are no other pro-European forces likely to cross the parliamentary threshold — partly the fault of PAS itself.

According to Isac, Moldova's proportional electoral system plays a key role here. It sets a 5% national threshold for parties, 2% for independents, and 7% for electoral blocs — a steep hurdle for newcomers.

"Add scarce funding, shallow local organizations, and a volatile, leader-centric party culture, and many pro-EU initiatives fail to scale or to survive beyond a single cycle," Isac said.

Attempts to build alternatives often collapse due to internal splits or defections to other parties — fueling voter skepticism about the viability of smaller pro-European movements.

"The legacy of past pro-European governments tainted by oligarchic capture also depresses trust in new centrist projects. This is also a calculated political strategy of PAS, which took over numerous local chapters of pro-European parties," the expert added.

Under these circumstances, PAS and Sandu are left to bet on mobilizing their base to ensure proportionally more of their voters show up at the polls than pro-Russian supporters. At the same time, all parties are targeting undecided voters.

For PAS, there are two main approaches to this group, political analyst and CEO of PGR Consulting Group LLC, Ruslan Rokhov, told RBC-Ukraine. The first is explaining the risks of a pro-Russian victory. The second is aimed at "disappointed" voters who supported PAS before but grew disillusioned with the current government.

"These voters are being told: yes, the party made many mistakes, including with personnel and policymaking. But you must hold your nose and vote for it again, because otherwise there's a real risk of stopping European integration," Rokhov explained.

Symbolic pre-election gestures are also in play. For example, on September 25, Moldova extradited notorious oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc, once called the country's informal "owner." PAS is also counting on votes from the Moldovan diaspora in Europe, which last year secured Sandu's presidential victory.

Kremlin's forces marching in different columns

The main threat to Moldova does not come from openly pro-Russian parties. Since 2022, direct ties with Moscow have become too toxic. What's more, this gives Moldovan law enforcement additional tools to act against such political groups.

A vivid example is the series of projects by oligarch Ilan Shor, who is currently hiding in Moscow. Several of his parties have already been barred from elections on national security grounds, while some of their leaders have even ended up behind bars.

For several electoral cycles now, the focus has shifted to camouflaged Kremlin allies. This year, they are marching in several columns. The first is the Patriotic Bloc, led by former Moldovan presidents Igor Dodon and Vladimir Voronin. They court moderate pro-Russian voters.

For Moldovan nationalists, Moscow has also prepared its own project – the Greater Moldova Party. Its leader, Victoria Furtună, for example, has openly declared plans to annex Ukraine's Odesa region. Her current rating is just 2.1%, but the party shouldn't be written off.

Finally, there is the Alternative Bloc. It could potentially become a key parliamentary partner of the Patriotic Bloc, but for now, it hovers around the electoral threshold. The party claims to support European integration, but criticizes PAS and Maia Sandu.

Igor Dodon and Vladimir Putin (Photo: Getty Images)

According to Moscow’s design, the Alternative Bloc was supposed to attract pro-European voters disillusioned with the current government. At the same time, the party's leaders have long-standing ties to Russia, and the party itself has effectively become a platform for old political elites to return to power, said Marianna Prysiazhniuk, analyst at the Democratic Initiatives Foundation and coordinator of the Delta-24 project on Ukraine, Moldova, and Romania.

The party's leader, Chișinău mayor Ion Ceban, was previously a member of the pro-Russian Communist and Socialist parties. More importantly, he took part in the 2014 Gagauzia referendum on whether to align with the EU or with Russia's Customs Union – a referendum declared unconstitutional by central authorities. Other leaders also carry heavy baggage, such as former Prime Minister Ion Chicu and Alexandru Stoianoglo, Maia Sandu's main rival in last year's presidential election.

"All of these figures have spent the past few years whitewashing their image and presenting themselves in a rebranded format. What's interesting is that they have tried to boost their credibility partly by leveraging ties with Ukraine," Prysiazhniuk explained.

According to her, party representatives in Ukraine advocated various initiatives, released communications, and gave commentary – all to present themselves as pro-European through their links with Ukraine.

The Alternative Bloc was weakened through a combination of measures. First, a media campaign highlighted the murky past of its leaders. Then, in July, neighboring Romania banned Ceban from entering the Schengen zone on national security grounds. This sent a clear signal to pro-European Moldovans that the Alternative bloc poses a threat despite its leaders' rhetoric.

In the final stage of the campaign, pro-Russian forces have mostly resorted to spreading fake news, scaring the population with narratives of a looming war with Russia.

According to Bloomberg, Russia has drawn up a multi-layered plan to interfere in the elections. The document seen by the agency outlines organizing protests, running a large-scale disinformation campaign on social media, and other measures. While its authenticity remains in doubt, some points are already being carried out in practice.

"As I'm in Chișinău now, TikTok is pushing me to local content. I saw, for example, fake posts with PAS ads claiming that once PAS wins, Moldova will join Ukraine in fighting against Russia," said Rohov.

In mid-September, Maia Sandu told the Financial Times that Moscow was also using Russian Orthodox priests to spread propaganda among the Moldovan diaspora. The Kremlin is managing a bot network called Matryoshka, which produces fake content disguised as legitimate foreign media. She noted that Russia's tactics are constantly evolving. For instance, mercenaries funded by Moscow are now also being involved in stirring up unrest in Moldovan prisons.

All these factors are significant, but exactly how many columns the Kremlin will eventually manage to bring into Moldova's political system remains unclear.

Possible surprises

Sociological polls in Moldova do not take into account a number of factors. On one hand, there is the diaspora in Europe. In last year's presidential election, votes from Moldovans abroad were decisive in Maia Sandu's victory. This time, however, things could turn out differently.

"I think more than half of the diaspora would definitely vote for the Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS). The question is that when the number of voters increases, there can be some deviations, because more polling stations have been opened and more ballots provided for the diaspora," said Rokhov.

One key factor is Romania. According to official Moldovan government data, over a million Moldovan citizens also hold Romanian passports. Recently, the far-right leader of Romania's AUR Party, George Simion, who nearly became president this spring and holds pro-Russian views, urged his supporters not to vote for PAS and to back another party instead – Democracy at Home.

This populist party, which polls at 3.1%, is allied with Simion's Romanian radicals. So part of the diaspora may listen to Simion and help bring another party into parliament. Last year's elections in Romania showed that Simion has significant support among the diaspora. However, Marianna Prisyazhnyuk underlines that Moldovan and Romanian diasporas view the authorities in their home countries differently. Loyalty to Sandu may therefore be higher among Moldovans abroad.

"The difference is that Romanians in the diaspora often criticize politicians in their own country because they have partially adapted to the new countries where they have settled. Moldovans, on the other hand, always feel connected to the Republic of Moldova, to the territory they came from," Prisyazhnyuk said.

Moldovan citizens at a rally in Bucharest, 2015 (Photo: Getty Images)

Moldovan citizens at a rally in Bucharest, 2015 (Photo: Getty Images)

Another factor influencing the elections is the voters in Transnistria. The Moldovan government does not control this unrecognized republic, but its residents have the right to vote, mostly for pro-Russian parties. According to Rokhov, this could provide an additional 2% of votes, most likely for the Patriotic Bloc.

Finally, there is the "Shor network" factor. This is a unique phenomenon in European politics. A fugitive oligarch, funded by Russian money, has created a network for mass voter bribery, which can be activated at critical moments during elections. The specific mechanisms of bribery change from election to election, especially as the authorities try to fight Shor. But his influence has not completely disappeared.

The scale of the "Shor network" is still not fully clear. Authorities have previously claimed that around 300,000 people were involved, roughly 20% of the votes. This figure is likely exaggerated. But Shor's clients are still numerous enough to help one of the pro-Russian parties that are short by a few thousand votes – Alternative Bloc, Greater Moldova, Democracy at Home – or simply to distribute votes evenly among them.

Regardless of the election results – whether a weak coalition forms around PAS or pro-Russian forces take control of parliament – Moldova remains politically divided. Its biggest problem is that there is no force capable of uniting the country, even in the foreseeable future.