Soviet deportation and Russia's ongoing crackdown on Crimean Tatars

On May 18, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide (photo: Getty Images)

On May 18, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide (photo: Getty Images)

On May 18, 1944, at six in the morning, the USSR began the deportation of Crimean Tatars from their native peninsula. People were given no more than 30 minutes to gather their belongings. In just a few days, over 190,000 Crimean Tatars were forcibly relocated to special settlements in Central Asia. They remained separated from their homeland for nearly five decades.

On the day of remembrance for the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide, RBC-Ukraine highlights another crime against humanity committed by the USSR and how Russia continues to take away the native land of these people.

Eradicating a people from their homeland

Before the deportation, 218,000 Crimean Tatars lived on the peninsula, according to the 1939 Stalin-era census. They made up nearly 20% of Crimea’s population at the time.

The deportation took place between May 18 and 20, 1944. Crimean Tatars were transported in trains to Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the Urals. Even Crimean Tatars serving in the Red Army were not spared. After the war, they were sent thousands of kilometers away from their homeland.

"The goal of the deportation was to eradicate the indigenous population of Crimea. Another objective—Stalin, before the end of World War II, was trying to negotiate with Western partners to pressure Turkey in order to gain access to the Bosporus Strait, the passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Therefore, he wanted to eliminate strong Muslim communities in surrounding regions such as Crimea and the North Caucasus, which could obstruct this pressure," explains historian Roman Kabachiy, senior researcher at the Museum of the History of Ukraine in World War II.

Alongside the deportation of Crimean Tatars, the Soviet authorities also forcibly relocated Greeks, Bulgarians, Armenians, and Germans. They were accused of collaborating with the Nazis. In most cases, there was no evidence to support these accusations.

A Crimean Tatar boy deported from Crimea for "betraying the Soviet Union" — "collaborating with the Germans" (photo: Wikipedia)

"Back in 1941, when the German-Soviet war began, ethnic Germans were deported from Crimea and other Black Sea regions of Ukraine. They were seen as a suspicious element who might aid the occupiers against the Soviet Union. So by 1944, the USSR already had a practice of deporting ethnic minorities," the historian adds.

Crimean Tatars were forced to leave everything behind — they were only allowed to take their documents. During the journey, due to inhumane transport conditions, heat, and lack of food, 191 people died, according to official figures. In reality, the number was much higher.

"This was a carefully planned operation — essentially genocide — because it aimed to sever a people from their homeland and assimilate them into other populations. Often, those deported were people who had just the day before shared meals with Crimean Tatar families. The current head of the Mejlis, Rafat Chubarov, has spoken about such cases," Kabachiy says.

The Soviet authorities effectively banned even the use of the name "Crimean Tatars": they insisted on calling them simply "Tatars."

"In Poland, ethnic group names are capitalized. When Poles use the old spelling and write "Tatars" with a capital letter but "Crimean" with a lowercase, they reduce this people to an ethnic subgroup of a larger nation. In fact, Crimean Tatars and Kazan Tatars are distinct," the expert explains.

In the late 1940s, Crimean Tatars began to flee in large numbers, breaking the special settlement regime and demanding the right to return home. In the 1960s and ’70s, the authorities occasionally allowed small numbers to resettle in Crimea.

Later, the ban on Crimean Tatars returning to the peninsula was lifted, but they were not permitted to register residency there. As a result, many settled in nearby regions such as Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. Mass returns to their homeland began in the late 1980s.

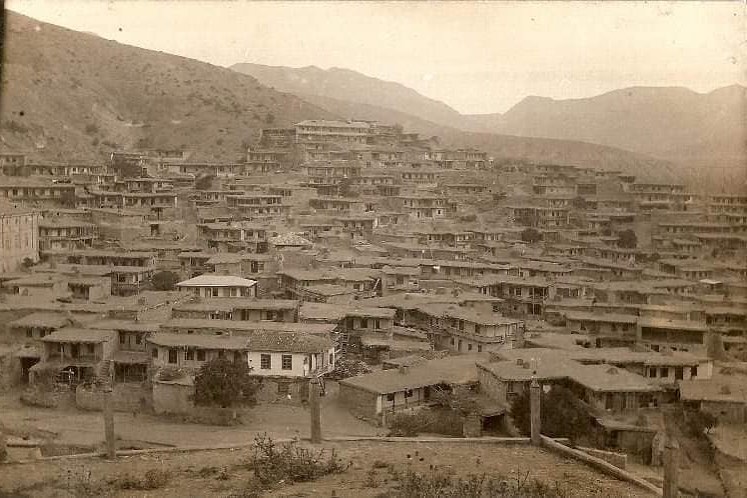

An empty Crimean Tatar village Uskut (photo: Wikipedia)

Occupation of the peninsula — another tragedy for Crimean Tatars

After Russia’s annexation of Crimea, about 50,000 Crimean Tatars left their homeland. Over a hundred became political prisoners of the Russian Federation, and many activists died due to persecution by the occupiers.

"Another tragedy is unfolding before our eyes. Constant searches, the classification of the religious organization Hizb ut-Tahrir as a terrorist group, imprisonment for so-called 'citizen journalism' — this is pressure on the people. Some cannot endure it and leave the occupied peninsula. But there are cases when people return because for Crimean Tatars there is only one homeland — Crimea," says Kabachiy.

Crimean Tatars in Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions effectively experienced a double deportation — after the full-scale Russian invasion, they had to leave their homes again in 2022.

"Mejlis member Gulnara Bakirova, who lived in Novooleksiivka, Kherson region, before the full-scale war began, fled after burning all her family photos," Kabachiy says.

Family stories and hope for return

At the Museum of the History of Ukraine in World War II, within the exhibition space "Ukraine — crucifixion," there is an exhibit called "In the portrait of ancestors is my homeland." Here, prominent Crimean Tatars shared photos of their ancestors who survived the deportation.

The exhibit includes photos of photographer Emine Ziyatdinova, director and actor Akhtem Seitablaiev, director Namir Aliyev, Verkhovna Rada deputy Tamil Tashev, Mejlis member Gulnara Bakirova, chief editor of Ukrainska Pravda Sevgil Musayeva, deputy director of the Ukrainian Institute Alim Aliev, artist Rustem Skibin, and the first secretary of the Ukrainian embassy in Uzbekistan Yusuf Kurkchi.

Roman Kabachiy shows the exhibit "In the portrait of ancestors is my homeland" (photo: RBC-Ukraine/Vitalii Nosach)

"The oldest photos in the exhibition date back to the early 20th century. They show the great-grandfather and great-grandmother of Emine Ziyatdinova. Yusuf Kurkchi shared a photo of his father Ibrahim standing next to Mustafa Dzhemilev in Uzbekistan on Mount Chirchik, where active Crimean Tatar youth gathered to discuss possibilities for return. Sevgil Musayeva provided a photo of her mother and grandmother, who used to travel for holidays to Feodosia until they returned to Crimea permanently," the historian says.

All captions for the photos are provided in Ukrainian, Crimean Tatar, and English.

"Each photograph here carries its own message. This exhibition is not our first initiative. In 2017, we published the book Wormwood May 1944, which collected testimonies, documents, and photos of the deportation, as well as illustrations by artist Rustem Eminov. So the topic of Crimean Tatars remains very much alive for us," the historian adds.

Well-known Crimean Tatars shared family photos (photo: RBC-Ukraine/Vitalii Nosach)