Oleksandra Exter: Dramatic story of Ukrainian avant-garde artist who conquered Paris

Who is Oleksandra Exter and why did the USSR destroy some of her paintings (RBC-Ukraine collage)

Who is Oleksandra Exter and why did the USSR destroy some of her paintings (RBC-Ukraine collage)

Oleksandra Exter is one of the brightest figures of the European avant-garde of the 20th century, a Ukrainian artist, designer, and stage designer whose work passed through Cubo-Futurism, Suprematism, and Constructivism. Her road to recognition was difficult and dramatic, and her life became a personal struggle for self-expression.

Who was Oleksandra Exter

Oleksandra Exter (Hryhorovych) was born on January 18, 1882, in Białystok of the Grodno Governorate (now Poland), into the family of a wealthy entrepreneur. Her father was a Belarusian Jew, and her mother was Greek.

After Oleksandra’s birth, her parents moved to Kyiv, where she received her education at the Kyiv Art School.

She became one of the central figures of Cubo-Futurism and Constructivism—art movements that broke the canons of traditional painting and opened a new format of visual thinking.

Her vision was radically innovative: the use of color and form had a kinetic, emotional impact, marking a departure from figurativeness.

A pioneer of European Cubism and Futurism, the avant-garde, and one of the founders of the Art Deco style. She became an abstractionist—something her friends Picasso, Braque, and Léger did not dare to do at the time. She also renewed 20th-century theatrical art, designing stage action in a novel way that was later adopted in Europe and America.

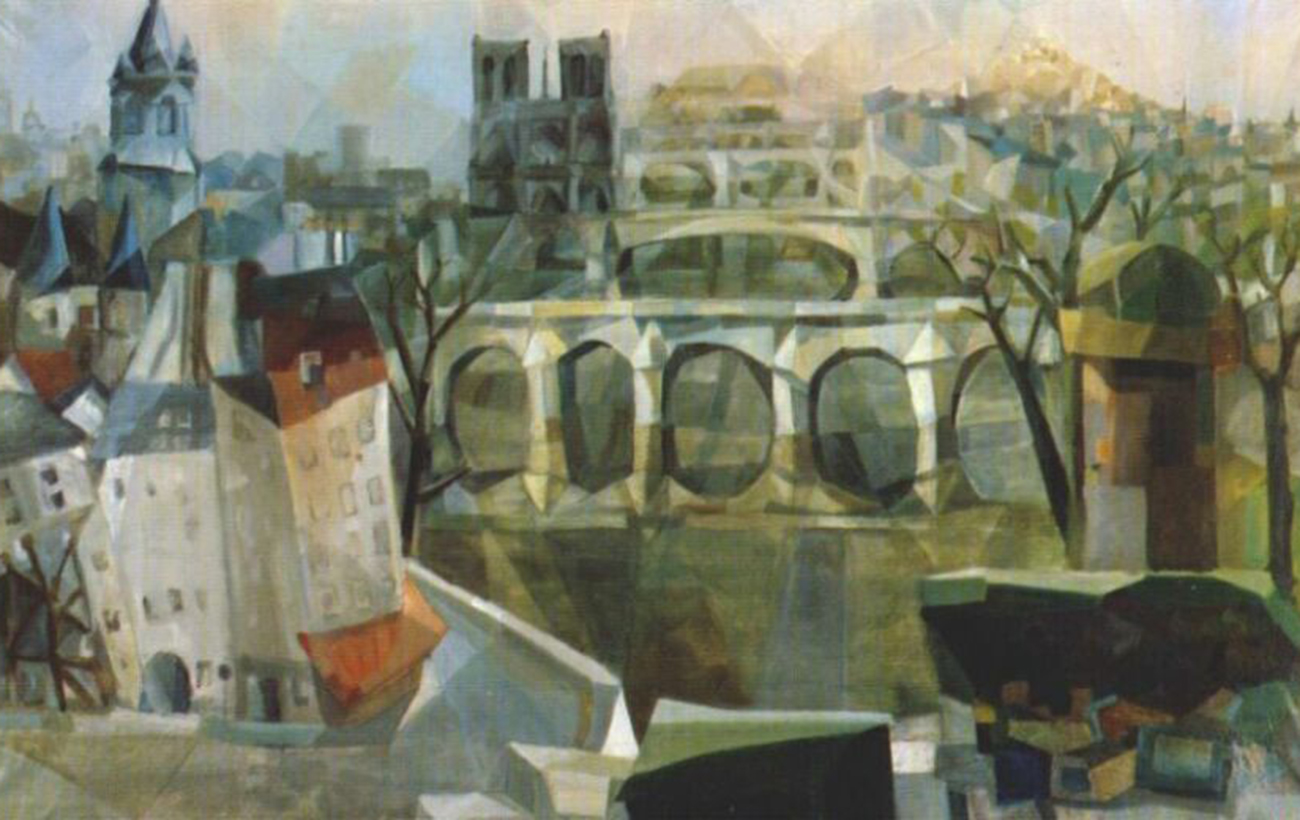

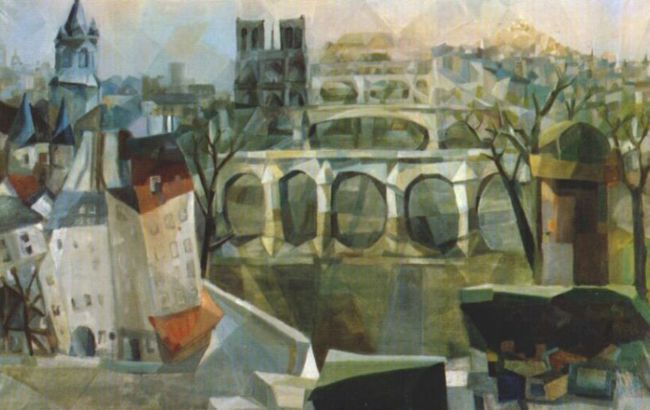

Paris Landscape, 1912, Oleksandra Exter (photo: Wikipedia)

She married the German lawyer Mykola Exter and lived in Kyiv on Bohdan Khmelnytskyi Street. In the attic of her house, there was a studio where not only she worked, but also future talented artists Vadym Meller, Anatol Petrytsky, Pavlo Tchelitchew.

In 1907, she traveled to Paris for the first time, where she met Guillaume Apollinaire and ended up in Pablo Picasso’s studio.

According to her friends, wherever Oleksandra lived, there were always Ukrainian carpets and embroideries in her home. And varenyky were served in Ukrainian dishware.

The drama of life: revolutions, war, and the search for one’s place

Exter’s life crossed with several major historical upheavals. After her early years in the artistic circles of Paris and Kyiv, the artist faced the First World War in Russia, where she became an active figure of the avant-garde.

She taught at her own studio in Kyiv, where her students were future figures of theater and cinema, and worked with theatrical directors, including Alexander Tairov, designing sets and costumes for provocative productions.

_1.jpg) Still Life, 1913, Oleksandra Exter (photo: Wikipedia)

Still Life, 1913, Oleksandra Exter (photo: Wikipedia)

One of the first exhibitions in the style of abstractionism, Lanka, caused a real shock—the new art was not accepted. She was criticized by everyone—from teachers and the older generation of artists to representatives of high society.

Ukrainian motifs and embroidery

Later, Exter and her friend Natalia Davydova, together with other researchers, began to search for folk motifs, which they reinterpreted, modernized, and embodied in Suprematist designs for embroidery on various items such as bags, pillows, carpets, belts, and more, collaborating with Kazimir Malevich, Ivan Puni, and Xenia Bogoslovskaya. And also working based on sketches by Rozanova and Udaltsova.

Later, they founded the Kyiv Handicraft Society and presented their Verbivka embroideries at exhibitions in Kyiv and in European countries. The exhibitions were successful. In 1917, more than 400 works were exhibited in Moscow, but they never returned.

Non-Objective Composition, 1917, Oleksandra Exter (photo: Wikipedia)

Non-Objective Composition, 1917, Oleksandra Exter (photo: Wikipedia)

In 1918, Oleksandra lost her husband. Already at the beginning of 1919, she, together with her late husband’s mother, was forced to leave her native city, as it had been seized by the Bolsheviks. Thus began the artist’s life in emigration, because she was no longer able to return home.

Several months in Odesa, a brief return to the capital, and then, in search of work, she ended up in Moscow. From there, she went to the Venice Biennale and never returned.

The horrors of the revolution and the civil war led to losses: part of her works were destroyed or scattered, and life circumstances required adaptation.

Oleksandra Exter (photo: exter.net)

Oleksandra Exter (photo: exter.net)

Did not fit into socialist realism

The Soviet Union did not need art that did not fit into the canons of socialist realism. That is why, while Oleksandra was traveling and arranging her life abroad, part of her paintings simply disappeared.

As later became known, on the authorities’ orders, they ended up in the “special fund” as art that “distorted socialist reality.” They were to be destroyed.

Dancers, 1924, Oleksandra Exter (photo: Wikipedia)

Dancers, 1924, Oleksandra Exter (photo: Wikipedia)

By a miracle, several paintings were saved, and only two decades later, they were transferred to the National Art Museum of Ukraine.

Oleksandra Exter’s name is included in the list of the Russian pantheon of artists (where there are many Ukrainians). The USSR destroyed her paintings and now uses the name of the Ukrainian artist to glorify "the great Russian culture.”

Exter was forced to move to Paris in 1924, where artistic movements were changing, and interest in abstract painting was declining.

Exter in Paris: emigration and creative decline

In Paris, Exter continued to work as a teacher at the Académie Moderne, collaborated with Fernand Léger, and created designs for ballet, theater, and cinema.

Despite her talent, life in emigration was difficult. The decline of opportunities in modern art, health problems, and lack of support gradually pushed her away from the center of the European scene.

In her final years, she lived in Fontenay-aux-Roses, where she died on March 17, 1949, leaving a vast but partly forgotten legacy.

Exter bequeathed her works and archive to her artist friend Simon Lissim, who lived in New York. Most of Exter’s legacy ended up in America.

Today, Oleksandra Exter’s works are held in various museums around the world. The National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv, where she began her creative path, also keeps her works.

Sources: Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine, Association Alexandra Exter, Ukrainska Pravda.

Read also