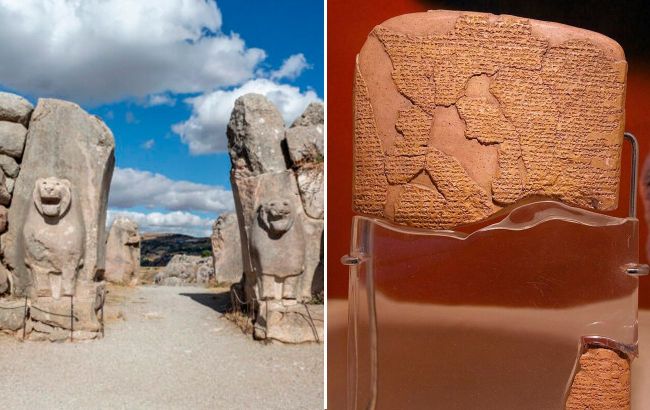

Archaeologists discover lost language dating back 3000 years

Archaeologists discovered a lost ancient language (Collage by RBC-Ukraine)

Archaeologists discovered a lost ancient language (Collage by RBC-Ukraine)

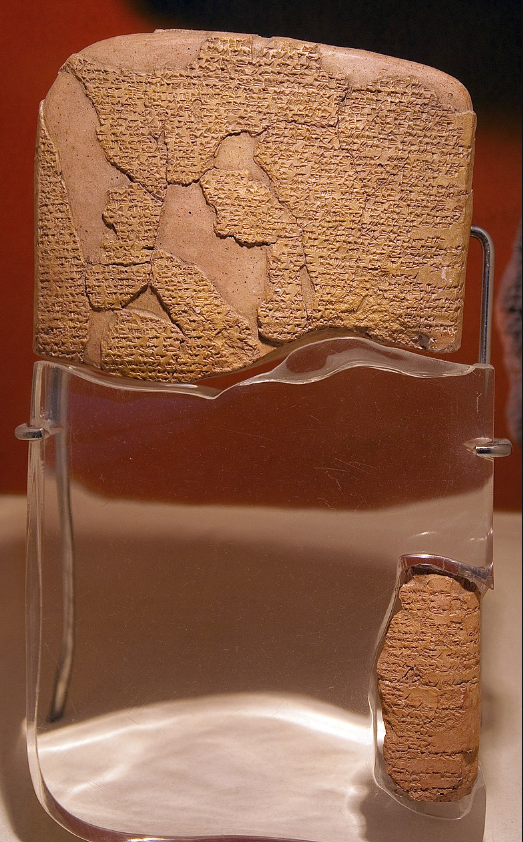

A secret text has been found in Türkiye scattered among tens of thousands of ancient clay tablets dating back to the Hittite Empire in the second millennium BCE. The intriguing cuneiform, according to archaeologists' preliminary data, represents a lost language that existed over 3000 years ago.

What is known about this language is detailed by RBC-Ukraine, based on Science Alert.

Experts say the secret text and its enigmatic idioms don't resemble any other ancient written language found in the Near East. However, it certainly shares roots with other Anatolian Indo-European groups.

The intricate patterns begin at the end of a cultic ritual text written in Hittite—the oldest known Indo-European language. The phrase following the introduction translates as "From now on, read in the language of the country of Kalašma."

Kalašma was an organized Bronze Age society, likely situated on the northwest periphery of the much larger Hittite Empire in ancient Anatolia, at some distance from the Hattusa capital where this clay tablet was later discovered.

The head of the archaeological excavations at the ruins of Hattusa, Andreas Schachner, shared that upon first touching this tablet, he immediately sensed its significance. He notes that this clay tablet has remarkably survived compared to the other 25,000 found in the same place in modern-day Bogazkale, Türkiye.

For nearly a century, historians, archaeologists, and linguists have collaborated to decipher and translate this incredible archive of royal treaties, political correspondences, legal, and religious texts from Hattusa.

Most tablets are written in Hittite cuneiform, but experts have identified other languages. The scripts seem to stem from various ethnic groups existing in the shadow of the Hittite Empire during its rule over most of Anatolia from 1650 to 1200 BCE.

Map of the Hittite Empire at its greatest at its greatest extent, c 1300 BCE. (Ennomus/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY SA 4.0)

Map of the Hittite Empire at its greatest at its greatest extent, c 1300 BCE. (Ennomus/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY SA 4.0)

"The Hittites were uniquely interested in recording rituals in foreign languages," say archaeologists.

However, it wasn't solely for scholarly reasons. The Hittite Empire, most likely, glorified thousands of gods and goddesses. As the Hittites expanded across the vast peninsula between the Black and Mediterranean Seas, they developed new religions to attract the newly conquered to their fold. In doing so, they sought to gain the respect of the conquered people.

"Embracing these gods with no self-pantheon indicates the existence of a tolerance culture," explain researchers.

Borrowing ideas, such as cuneiform writing systems, traditions, and religions, was likely a way to expand the empire's sphere of influence.

For instance, the Kalašmans fought alongside the Hittites against the Egyptian Empire in the battle of 1274 BCE.

"Clay tablet with a detailed description of the Kadesh Treaty found in Bogazkoy, Türkiye. (IoKan/Wikimedia Commons)

Currently, experts are working on translating a recently discovered tablet with Kalašmaic script. Schachner and his colleagues hope to publish their findings along with an image of their discovery next year.

Previously, we wrote about archaeologists discovering an entire cache of female ornaments from the Bronze Age.