Ukraine's first constitution isn't even in Ukraine — historian Oleksandr Alfiorov

Historian Oleksandr Alfiorov (screenshot)

Historian Oleksandr Alfiorov (screenshot)

Who actually authored the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk, and why is it considered groundbreaking for its time? Which principles of the Cossack constitution should be integrated into modern legislation? How was Ukraine's main law adopted in 1996, and what’s wrong with it today? Read the answers in an interview on RBC-Ukraine.

Key questions:

- How did Pylyp Orlyk's Constitution appear, and why was it revolutionary for its time?

- Which of Pylyp Orlyk's ideas remain relevant even in the 21st century?

- In search of the truth. How was the Ukrainian-language version of the constitution discovered in Moscow?

- Compromises with the communists. How was Ukraine's modern constitution adopted, and what’s wrong with it?

- Does Ukraine's constitution meet the demands of the times, and is there a need to change it under Russian pressure?

In 1710, when most European states had not yet even dreamed of the separation of powers or social guarantees, Ukrainians already had a document that provided for such things. It's about Pylyp Orlyk's Constitution – a unique act created in exile after the defeat near Poltava, but written with a clear vision of an independent state.

After more than two and a half centuries of struggle for sovereignty, Ukraine received its modern Constitution, adopted on June 28, 1996. It enshrined the foundations of democracy, rights, and freedoms, which Ukrainians continue to defend to this day.

PhD in History and head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, Oleksandr Alfiorov, spoke in an interview with RBC-Ukraine about how Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution was born, what was truly revolutionary in it, and how Ukraine’s current main law was adopted.

How Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution was born: Historical background and preconditions

– Under what historical circumstances was Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution created in 1710?

– Constitution Day reminds us of the vast constitutional tradition in our lands. In the world, constitutions were adopted at the end of the 18th and in the 19th centuries: the American, then the Constitution of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and others. Great Britain has no written Constitution, but it is the first democratic state in Europe.

The history of constitutional acts is the history of written law. We have the Rus’ka Pravda of Yaroslav the Wise, its versions, the Statutes of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, hetman decrees, and the Rights by which the Little Russian people are judged. These are the acts that enrich our legal thought.

In 1710, an event of global importance occurred – the creation of a document called Pacta et Constitutiones, or in the Ukrainian version – Treaties and Resolutions of the Zaporizhian Host. The document is also called the Bender Constitution, since it was signed in the Bender Fortress, or the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk. This is a phenomenal event, which was destined to happen in Ukraine due to certain political and military circumstances.

This Constitution was born in difficult conditions. The allies Ivan Mazepa and Charles XII, who united against the Moscow tsar, lost the battle of Poltava. The Swedish and our armies retreated to Bendery, then under Ottoman rule. So the King of Sweden and Hetman Ivan Mazepa ended up in exile.

Though it’s called the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk, I’m convinced it was conceived by Ivan Mazepa. At that time, the Cossacks needed to conclude a social contract among themselves, and only then a union treaty with Charles XII. The Constitution document was created, but Mazepa died, and Orlyk signed the document. It was later translated into Latin and signed by Charles XII.

Oleksandr Alfiorov (screenshot)

– How were the interests of the Hetman, the Cossack elite, and the Zaporizhian Host balanced?

– Orlyk wrote the Constitution from the perspective of future hetmanship, the Zaporizhians wrote their section, seeking guarantees. The Cossack elite also contributed, wanting to limit the Hetman’s powers, while he sought to limit the elite’s rights, and there were also representatives of the townspeople. So all interests were balanced.

The Constitution has a preamble explaining who we are and our thousand-year history. The first thing it states is that we belonged to the Orthodox Church of the Constantinople Patriarchate. The Cossacks understood that a foreign church was wrong.

The Constitution contains a unique feature in terms of legal and philosophical thought of that time – a division into separate executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Moreover, the document was effective. In 1711, Pylyp Orlyk entered the Right Bank of Ukraine as Hetman and governed based on the laws he had signed – the Constitution.

Therefore, the Constitution was effective and modern. And the fact that the world doesn’t know about it – that’s our fault. But had we won then, we could say – here is the first Constitution, not the American or the Polish one.

– Even now, one can encounter the claim that Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution was the first in Europe. Is that a justified title?

– From a 300-year perspective, it’s hard to say definitively, but in many ways – we had the first Constitution in the world.

The search for the document: How the Ukrainian-language copy was discovered in Moscow

– I know that you found the Ukrainian-language version of Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution in the Moscow archives in 2008. How long did the search take, and how did you manage to find it?

– We knew the content of Pylyp Orlyk’s Constitution. It had been published multiple times in the 1990s, and we had a Latin copy. It was supposedly discovered by Ilko Borshchak in exile in the Château de Dinteville, which belonged to Orlyk’s son through his wife. But we had no Cyrillic manuscript. Scholars had traveled there, but didn’t find the Ukrainian version.

In 2008, tensions between Russia and Ukraine were already escalating, especially after the Orange Revolution. It affected the ideological level. Independent media in Russia had already disappeared, and propaganda began. The Russians mocked us: “Ukrainian first constitution? What next – Christ was Ukrainian? At least we see Christ on icons. Show us your constitution.” And our scholars couldn’t show the document.

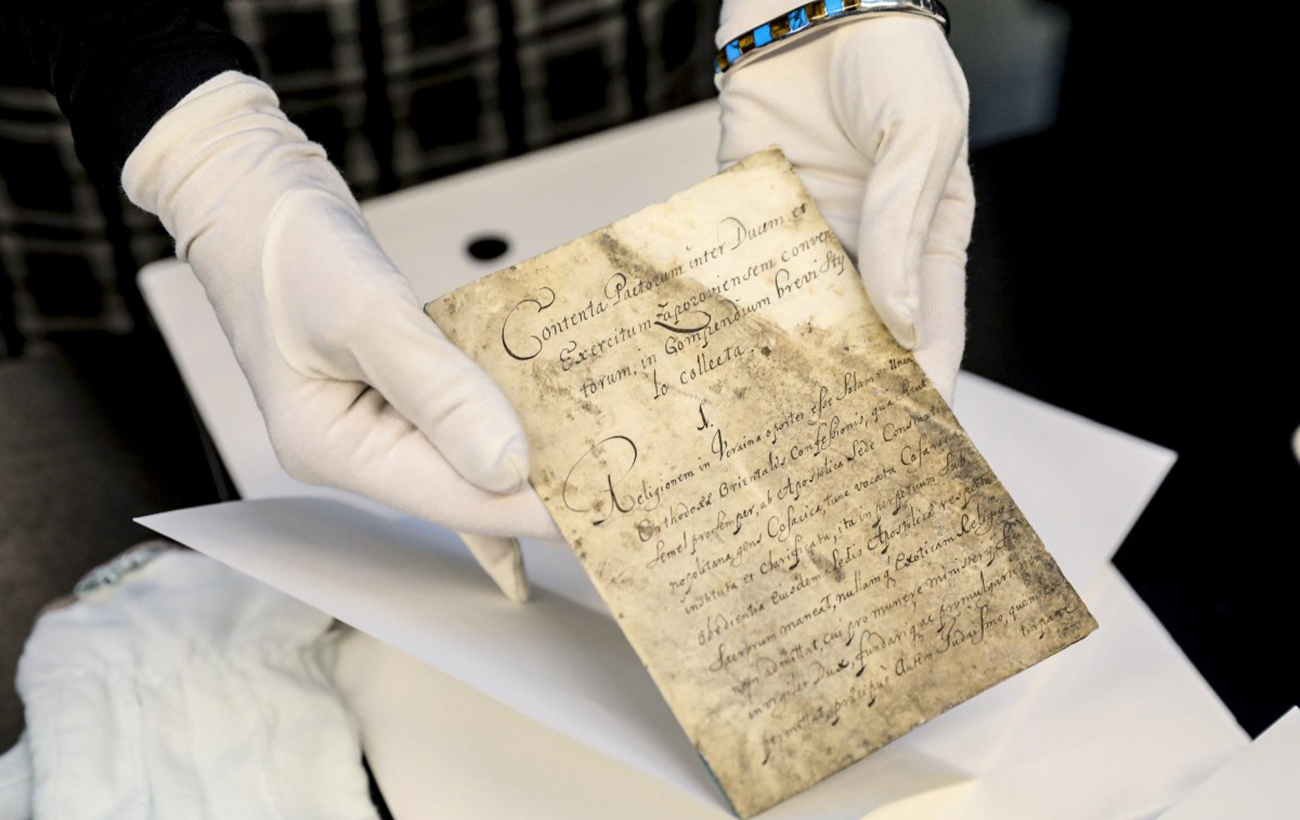

First page of the Constitution in Latin. The original is kept in the Swedish National Archives (photo: UNIAN)

Our entire collection of Cossack documents basically starts in the 1730s, since Peter I destroyed Baturyn, and a fire occurred in the hetman capital Hlukhiv (early 18th century - ed.). Meanwhile, Russia accumulated millions of documents related to the Cossack era.

So I went to the Moscow archive to study the registries of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, which I later published with my colleague Oleksii Monkin. At that time, Moscow archives were accessible, but our scholars lacked funding for research.

I had to secure a grant from Canada, pull strings to get dormitory accommodation, and even pay extra from my own pocket. Historians had meager salaries then. From 2010 to 2019, I worked at the Institute of History, earning 3,500 UAH. That was enough to give my kids and wife 23 UAH per day. Our country didn’t support its humanitarians, but Russia supported theirs.

They shaped the “Crimea is ours,” “Russia is Ukraine,” and “Lenin created Ukraine” narratives, etc. Our humanitarians were barely surviving; those who could get grants fared better, and such grants could come from Russians – hence, a large portion of people who ended up betraying Ukraine.

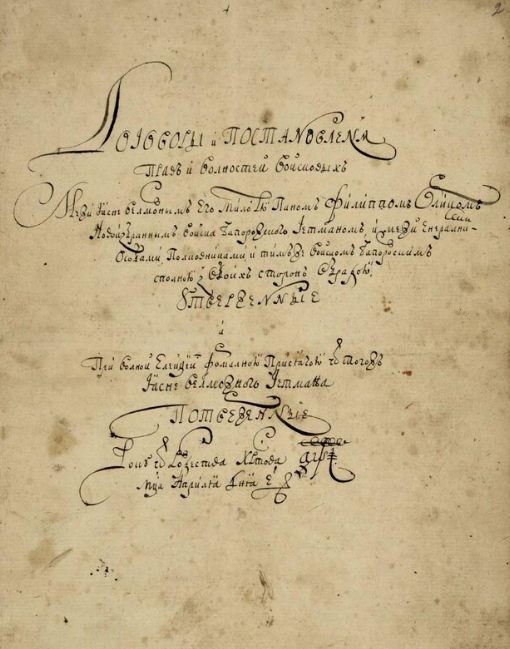

In the Moscow archive, I found a document describing a case titled “Treaty of the Zaporizhian Cossacks with Swedish King Charles XII.” They handed it to me – I still remember that adrenaline surge when I realized what was in front of me! I had tears in my eyes at that moment.

I then published the Constitution, and it stirred up public interest, but some of my colleagues reacted very negatively. How could a mere graduate student have found such a thing? Later, another copy was discovered.

– Unfortunately, the original is still kept in Russia. Will we be able to bring it to Ukraine?

– The original Constitution in the context of that time is a complex issue. I believe Pylyp Orlyk signed over a dozen copies, as they were given to the Zaporizhians, the Cossack elite. Where to search for them is a separate question. Currently, two copies are in Moscow, and one Latin version is in Sweden.

Copy of the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk in Old Ukrainian. The document is kept in the Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts (photo: Wikipedia)

A progressive constitution: The document’s main principles and ideas that are still relevant today

– Which principles of the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk were the most progressive at the time?

– Progressive was the fact that they said we must break away from the Moscow Patriarchate — at that time, they had been under the MP for just over 20 years. This was the first article to return to the throne of Constantinople. And we did return more than 300 years later.

There truly are progressive articles, for example, about social protection. Elderly and wounded Cossacks had the right to be cared for by the state in the Trakhtemyriv hospital. Cossack widows and children were also socially protected.

Another very interesting phenomenon — anti-corruption measures were written into the Constitution. Many articles and provisions were devoted to this — “So that the hetman’s heart would not be tempted by gifts.” So, the hetman could not accept gifts, because he received a salary. It was not in monetary form, but in the granting of land plots from which he made his living. How well he managed them — such was his income.

Also, the hetman could not interfere with the state treasury. The Constitution directly stated that the predecessor — without naming names, but it was Ivan Mazepa — had for some time not distinguished his personal income from state funds. And the treasury was shared. So the Cossacks decided to divide it — hetman's funds separately, state funds separately.

Colonels were also forbidden from accepting gifts. Corruption was a problem, and the Cossacks rooted it out — the hetman limited the rights of the officers in the document, and the officers, in turn, limited the rights of the hetman. They were writing the document jointly, and each side was pulling for its own articles.

The conflict of interest required the limitation of each group’s powers. The Cossacks separated the judicial, executive, and legislative branches of power. It is important that the judiciary was separated. The hetman and colonels were simultaneously judges over those who fell under the jurisdiction of the Magdeburg Law. And that’s why this Constitution was ahead of the documents of that time.

– Are there principles from the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk that are worth incorporating into modern Ukrainian legislation?

– When the Constitution was being written, the Swedish War was still ongoing, from 1700 to 1721. The Battle of Poltava was just one fragment. And in the Constitution, it is written that all prisoners must be returned from Moscow. That was a constitutional provision. It is relevant even today — how many of our Ukrainian prisoners are now in the hands of those beasts?

A modern constitution: how Ukraine adopted its main legislative document

– Tell us about the historical context in which Ukraine’s main law was adopted in 1996.

– The Act of Independence of Ukraine on August 24, 1991, and then the Resolution of the same day stated that we are a sovereign state and rely on the Constitution of Ukraine, but that was still based on the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR.

Ukraine gained independence then, but we had not yet won it. We were the ones who brought down the Soviet Union, despite the KGB machine. Unfortunately, we were not able to organize the lustration process. Our parliament was filled with communists. There were even “red bellies” who continued to number parliamentary sessions according to the Soviet count. Some enterprises paid taxes to Moscow, our SBU was still sending documents there until 1993, thinking it was all temporary.

Oleksandr Alfiorov: The history of the adoption of the Constitution of 1996 is connected with concessions to the communists (screenshot)

Back then, constitutional commissions were created to draft our main legislative document, but there were delays. A conflict arose between the parliament and the president. Leonid Danylovych Kuchma made a very clever move: he threatened to dissolve Parliament and hold a referendum. In Parliament, everyone understood that if Kuchma pushed the Constitution through a referendum, Parliament would lose all credibility.

As a result, MPs sat for 24 hours straight, introducing an incredible number of amendments to the draft Constitution. Even then, they did not adopt the coat of arms of Ukraine as they should have. In 1991, the Verkhovna Rada adopted the trident as the coat of arms by resolution. But in the Constitution, it says that the small coat of arms of Ukraine is the trident, and the large one is still being developed.

This story is tied to compromises with the communists. The communists were promised that the small coat of arms would be the trident, and the large one would be as they wanted: with wheat ears and stars. They were played very skillfully. The large coat of arms has still not been formally adopted, although it already appears on state symbols, hangs in the president’s office, etc.

– Which principles of the 1996 Constitution do you consider the best or most progressive at the time?

– Our constitution was prepared by highly qualified professionals. It is one of the best in the world, although it has some nuances. In the Soviet Union, they used to say their Constitution was the most democratic. It even stated that the republics had the right to self-determination, but there were no mechanisms for this self-determination.

And when that “most democratic” constitution was in effect, people were being put in psychiatric hospitals, politically inconvenient individuals were persecuted, killed, and sentenced to 20–25 years. The genocide continued, proxy wars were waged — they entered Afghanistan to fight the Americans. Wars in Korea, Vietnam. Just like now, Putin tries to change the narrative and says it’s all the West, but he’s fighting it on the territory of Ukraine. That’s their usual method.

So, compared to the Constitution of the Soviet Union, ours truly is the most democratic constitution in the world. Of course, it’s not without contradictions. For example, the document states that Ukraine is a unitary state, but there is an article about the Republic of Crimea, which is impossible in a unitary state. But those are complex issues that we haven’t addressed since the ’90s, but they existed.

Changes and challenges of war: Does the Constitution meet the new demands of the time?

– The Constitution has undergone some changes over nearly three decades. Which amendments do you consider the best?

– In 2023, MPs voted to change the name of “urban-type settlement” to “settlement.” This word never existed in the Ukrainian language — it’s a Russian hybrid from the 1920s. We had khutir (hamlet), village, town, city, and now, according to the Constitution — village, settlement, city.

The problem is that about 200 towns lost their status and became “settlements.” They should be called towns. Kozelets — the center of the Kyiv regiment — is now a settlement. It’s good that during Yushchenko’s time, Baturyn was politically granted city status; otherwise, today the Cossack capital would be a settlement. And there are a great many such towns — and this disconnects us from history.

I think we will restore it all after the war. Historians will have a lot of work. We will implement excellent reforms, I am convinced. Right now, there is a quota of trust in historians thanks to decolonization and de-russification, which proves that Ukraine was saturated with imposed names. They tried to make us feel inferior.

As head of the expert group on renaming in Kyiv, I am glad that many cities have followed our example, and we now have streets named after: Hetman Ivan Mazepa (not just I. Mazepa), Hetman Polubotok, Prince Volodymyr Monomakh — because status matters.

However, due to martial law, it is currently impossible to amend the Constitution. So we still have the Kirovohrad and Dnipropetrovsk regions.

– According to our Constitution, how strong is the legal position of the president?

– This has changed over time. Ukraine was a presidential republic, then the events of 2004 led to us becoming a parliamentary-presidential one. Oleksandr Moroz was pushing the idea to take powers away from the president and make it a parliamentary republic.

Since the 2000s, when the “Ukraine without Kuchma” protests began, society started narrowing the corridors of power. Previously, the authorities didn’t feel them. At that time, Gongadze was killed, there were mass protests. By 2005, we, together with the National Union of Journalists, had calculated that about 60 journalists had been killed while doing their jobs.

And these corridors of power are still being narrowed by civil society, because it is becoming more transparent, especially during the war. Today, it’s hard to imagine someone like Yanukovych or his ministers returning.

Oleksandr Alfiorov: Civil society is still narrowing the corridors of power because it is becoming more transparent, especially during the war (screenshot)

Oleksandr Alfiorov: Civil society is still narrowing the corridors of power because it is becoming more transparent, especially during the war (screenshot)

– Russia has repeatedly tried to pressure Ukraine to change its national course and give up on NATO. In your opinion, as a historian and former serviceman, is there any chance we will have to change this article in the Constitution?

– One state trying to change another state's constitution — on what grounds, under what conditions? Should we also write that we cancel our independence? Interference by another country in our supreme law is already a sign that we are dealing with a mentally unstable entity.

Russia is a parasitic state that cannot exist without twisting others’ arms and legs, without killing, without funding terrorists. Could France tell Germany to change its constitution? No one in their right mind would say that.

Khutin (Putin – ed.) recently said at a forum that they gave us independence, the USSR “allowed” it. He said, “They told us” there would be no NATO expansion eastward. Of course, when the Scandinavians joined NATO during the full-scale invasion, this “confused grandpa” basically got slapped in the face. And what was his response? Nothing — because he’s afraid.

– In your observation, how have Ukrainians’ attitudes toward the Constitution changed over the past 30 years?

– Moods vary. I am absolutely convinced that most Ukrainians have not read the Constitution. It’s good that it’s studied in school, but it’s an adult document that needs to be read from A to Z in adulthood. We must read the Act of Independence of Ukraine, which says: “In light of the mortal danger looming over Ukraine…” Imagine — August 24, 1991, and it turns out that not then, but now — this is the mortal danger.

We need to read, know, and understand the Constitution. Law means coercion, and when we say “I have the right,” it is the law that grants it. We must follow the law for everything to go well.