'If Antarctica melts, cities will go underwater'. Ukrainian polar scientist on working at the edge of the world

Polar researcher Oleksandr Poluden (photo: instagram.com_sashapoluden)

Polar researcher Oleksandr Poluden (photo: instagram.com_sashapoluden)

How Ukrainian polar researchers live and work in Antarctica, what threats emerge at the “edge” of the world, what is happening to the ozone hole, and what will happen if all the planet’s glaciers melt — read in an interview on RBC-Ukraine.

Key questions

- How are daily life, work, and leisure organized for polar researchers at the Akademik Vernadsky Station?

- What Ukrainian scientists study in Antarctica?

- What will happen to the ozone hole in the coming decades?

- Whether melting glaciers pose a threat to Ukraine?

- What makes this season at the station special?

Ukraine’s only polar station, Akademik Vernadsky, is located on Galindez Island in Antarctica, 15,500 kilometers from Kyiv. The wintering shift here lasts a year: for almost all this time, scientists live in isolation amid the icy ocean. Every day, they work so that humanity can understand where the climate is heading and what consequences this will have. Data collected at the station is later used worldwide.

“There are people who fall in love with Antarctica and come here many times. And there are those who will say: ‘No, this is not for me.’ I first came to the Akademik Vernadsky Station in 2012 as part of the 17th expedition. Back then, everything impressed me: new animals, equipment, duties, and technical tasks. A lot had to be learned from scratch. Now I am in Antarctica for the sixth time — this year I headed the expedition for the first time,” says polar researcher, meteorologist-ozonometerist Oleksandr Poluden.

RBC-Ukraine asked Oleksandr what it is like to live and work at the “edge of the world” and what research is currently being conducted at the Akademik Vernadsky Station.

Below is Oleksandr Poluden’s direct speech.

The path to a dream job

I studied at the Odesa State Hydrometeorological University and wanted to be an agrometeorologist. In my third year, when students were being assigned to specializations, I tried to apply for this field but saw myself listed under polar meteorology.

Ukraine has only one polar station, Akademik Vernadsky, and we were specifically trained for it. Up to 10 specialists like this were trained, but graduating classes were not annual.

I first applied to the 16th expedition, but I was told I lacked experience. To gain the necessary qualifications, I took a job in the meteorology department of the Central Geophysical Observatory named after Borys Sreznevsky. I went on expeditions to many meteorological stations across Ukraine.

After gaining experience, I applied again to the National Antarctic Scientific Center as part of the 17th expedition. Since then, my practice has continued. I was also a participant in the 19th, 21st, 23rd, and 28th expeditions. When I was offered to lead the 30th Ukrainian Antarctic Expedition, I agreed.

Meteorologist-ozonometerist, head of the 30th Ukrainian Antarctic Expedition, Oleksandr Poluden (photo: facebook.com AntarcticCenter)

Life in isolation

The team is always composed of half experienced winterers and half newcomers. Currently, the expedition includes eight scientists and five people responsible for station maintenance. We have three meteorologists and three biologists, as well as two geophysicists. The command staff includes a mechanic, a diesel engineer, a doctor, a cook, and a system administrator. Four of us are women.

The icebreaker Noosfera delivered us to the station on March 15. Along with the team, everything necessary for the expedition is delivered. A two-week handover period follows. Inventory is conducted, staff transfer all duties, and briefings are held on whether there are changes in observations, since our data is later used worldwide.

The icebreaker Noosfera (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

The icebreaker Noosfera (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Our food comes from South America: we eat Chilean potatoes, fruits, and grains, but we also have Ukrainian buckwheat. We drink only bottled water that we bring with us. The water we desalinate at the station is used only for laundry, cleaning, and showers. If needed, special construction materials can be delivered from Ukraine if they are hard to find or expensive in Chile or Argentina.

For the next 8–9 months after arrival, when everything around freezes, we are completely isolated. The first people we saw during this expedition were around the end of October, when the National Geographic Resolution vessel visited us.

The second time Noosfera came to the island was in early December: it brought fresh vegetables and fruits, as well as the seasonal team, an engineering group that checks whether anything was damaged over the winter, and additional scientists. We have very strong winds at the station, severe frosts, and a lot of icing. Technicians inspect everything and repair it if necessary.

Among snow, without sun and warmth

Among snow, without sun and warmth

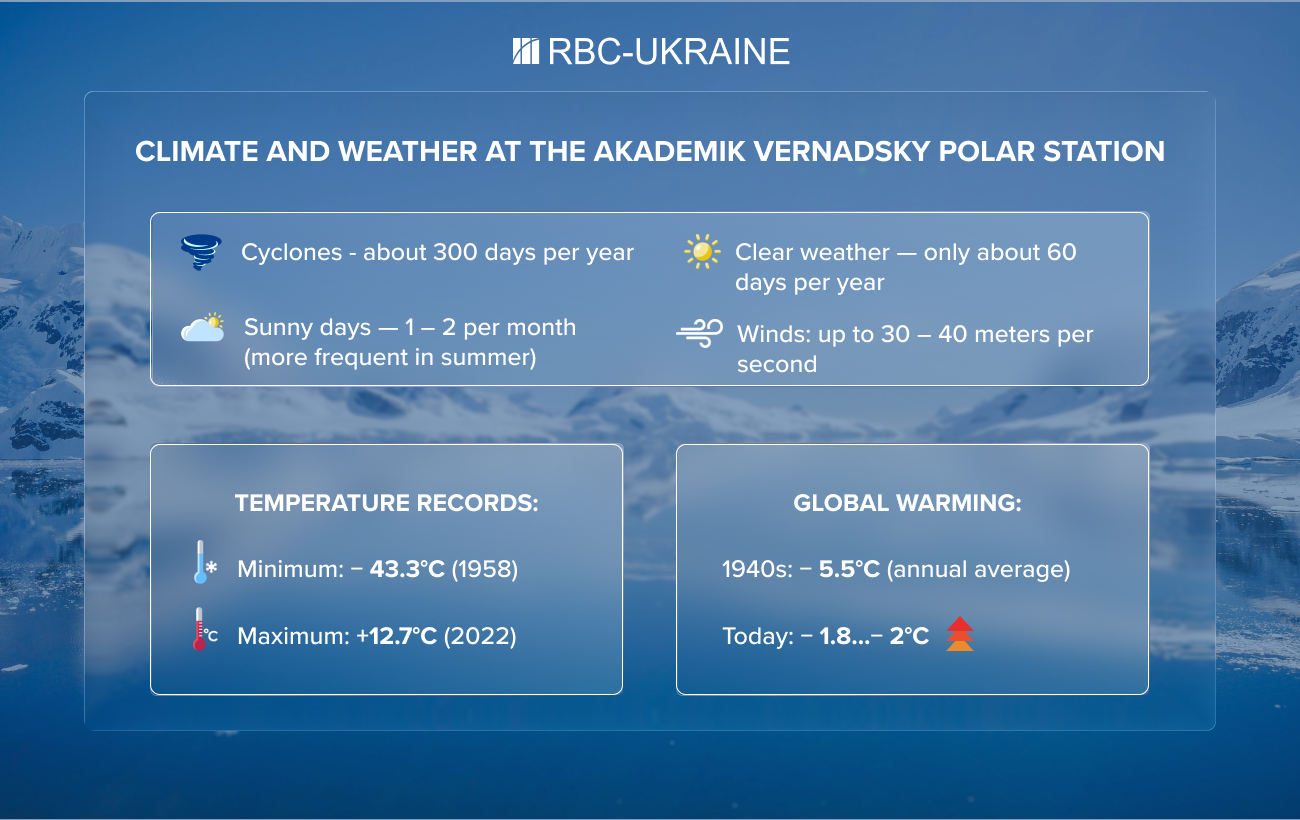

About 300 days a year, cyclones dominate here, coming from the north. Only about 60 days see anticyclonic activity, meaning clear weather. Sunny days occur mainly during the polar summer — December, January, and February. In other months, there are only one or two sunny days per month.

Severe frosts are rare. The lowest temperature recorded at the station was in 1958 - minus 43.3°C. The warmest was in 2022 at 12.7°C. Almost 80 years ago, the average annual temperature was minus 5.5°C; now it is around minus 1.8–2°C. This is global warming.

We currently have polar day, but from December 21, we gradually move toward night. Sunrises and sunsets here are not classic. Even in summer, when the sun disappears behind the mainland mountain ridge, it still remains light outside.

During the polar day, we have more work because we can carry out field tasks — going on expeditions to collect biological samples. Since the station is located 150 kilometers south of the polar circle, during the polar night, we have about three hours of twilight per day, and the rest of the time it is dark.

This period is harder to bear: people become less active, tire more quickly, sleep is disrupted, and the body does not understand when to sleep because it is almost constantly dark outside.

Life without civilization

Among the threats at the station are strong winds and snow. Wind gusts here can reach 30–40 meters per second. Icing and snowstorms tear cables and lines. Sometimes the station gets buried almost to the very top, and all this snow has to be cleared, otherwise it compacts.

Before being sent to Antarctica, we are told about all the risks, and experienced winterers share their knowledge. We try to take everything into account so that nothing extraordinary happens. People are selected for the station so that, potentially, they can replace one another in performing various tasks.

We have three diesel generators, one of which is always on standby. All instruments at the station are duplicated, so there are no interruptions in observations; if necessary, measurements can be taken again, and errors checked.

We do not really have days off — only the cook rests on Sundays. Everyone else takes turns cooking that day. In addition to main duties, each participant is assigned a specific area around the station to monitor and keep clear of snow throughout the year.

We clean the station daily, and every Friday we do a general cleaning. Only the cook and the night duty officer are exempt from this. After that, as expedition leader, I give the team some small gifts or treats — it might be a can of beer or a chocolate bar.

There are day and night duty shifts. Every hour, a person should walk through all buildings with life-support equipment, pumps, diesel generators, and desalination units. Temperatures, pressures, and various indicators must be monitored.

At the station, we sort waste. We have containers for paper, plastic, and food waste. There is a special unit that compresses it all, and after the expedition ends, we remove the waste from the island. The same applies to used oils — everything here is thought through down to the smallest detail.

Ukrainian Akademik Vernadsky Polar Station (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Ukrainian Akademik Vernadsky Polar Station (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Holidays and entertainment at the edge of the world

Our initiation into polar researchers takes place on Midwinter — the midwinter holiday on June 21. Newcomers immerse themselves in the icy ocean water, wearing only swim trunks and a tie.

When the team is selected, we instantly think about what gifts to bring with us, because we celebrate birthdays and all holidays here. This year, on St. Nicholas Day, the women knitted a large sock, and we drew notes from it telling who should prepare a gift for whom. Then the organizers placed them under pillows. You wake up in the morning, and there is a surprise waiting for you. This year, I received socks with dragons.

At the station, we follow Ukrainian traditions. On Christmas, we had kutia, varenyky with cabbage and potatoes, salads, and other Lenten dishes. The women sang carols. On New Year’s Eve, we had an artificial Christmas tree and champagne. First, we welcomed 2026 by Ukrainian time — we have a five-hour difference, and dinner is at 7 p.m. Then we celebrated by local time. We dressed in formal clothes, had a glass of champagne, and of course wished peace to Ukraine.

During the holidays, we hosted Norwegians who were living in tents on a neighboring island during a short-term penguin research expedition. We also had Mexicans stay with us for a couple of weeks as part of the first Ukrainian-Mexican expedition. Earlier this year, a Ukrainian yacht with tourists also docked here.

I tolerate long isolation well, and my family understands my expeditions. There is internet here; we can call home, communicate with management, and hold open online lessons for schools and universities. Each expedition participant has their own office, workspace, equipment, supplies, and living space.

The station has a gym, sauna, recreation room, and library. We have many board games. If there is time, we can watch movies. We have skis and snowshoes; we can go into the mountains or take motorboats out to sea. So everyone can do what they want in their free time.

We follow what is happening in Ukraine. We know that Zelenskyy flew to meet Trump regarding ceasefire negotiations. Each of us has air-raid alerts on our phones and is subscribed to Telegram channels of our home cities. We are constantly in touch with our families.

Thirty-one polar researchers are currently serving in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Even from the station, we help our “combat penguins.” We organize various fundraisers to cover their needs, take part in auctions, and conduct open lessons for donations — trying to raise as much money as possible to buy vehicles, generators, Starlink systems, and drones. We are grateful to people who donate, and of course, we also donate.

Entertainment for polar explorers during the expedition (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Entertainment for polar explorers during the expedition (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Entertainment for polar explorers during the expedition (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Entertainment for polar explorers during the expedition (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Entertainment for polar explorers during the expedition (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Entertainment for polar explorers during the expedition (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Animals of the icy continent

People often think that there are few animals and plants in Antarctica, but we have around 10 species of birds and several species of seals. In particular, about 7,000 subantarctic penguins live near the station, and occasionally emperor penguins visit us.

There are currently about 2,700 penguin nests with clutches. However, skuas still steal eggs from them. If we see that an animal is in trouble, we have no right to help it — this could disrupt the natural process and lead to unpredictable consequences. We also have no right to feed animals.

Only biologists are allowed to have direct contact with animals if they have a specific technical task. For the rest of the expedition members, certain distance limits are set for each species, defining how close they are allowed to approach.

There is still a widespread joking myth that polar explorers flip penguins over because they allegedly stare at planes flying over Antarctica, fall over, and cannot get up. In reality, penguins are very agile and can get up on their own without any problems.

At one time, it was possible to bring pets to the Akademik Vernadsky Station. But later changes were made to the Madrid Protocol on Antarctica, according to which it is now forbidden to bring non-native plants and animals here, so that they do not pose a threat to local species.

During the first expeditions to Antarctica, there was an interesting case. Researchers from the Northern Hemisphere brought dogs with them to harness them to sleds and go deeper into exploring the continent. But the polar explorers did not take into account that dogs from the Northern Hemisphere have different biorhythms in the Southern Hemisphere. When they brought them to Antarctica, winter had begun here, while the dogs felt that summer had arrived — they started shedding heavily, and it was impossible to use them for their intended purpose.

Animals living near the Akademik Vernadsky Station (photo: Serhiii Hlotov)

Animals living near the Akademik Vernadsky Station (photo: Serhiii Hlotov)

Animals living near the Akademik Vernadsky Station (photo: Serhiii Hlotov)

Animals living near the Akademik Vernadsky Station (photo: Serhiii Hlotov)

Animals living near the Akademik Vernadsky Station (photo: Serhiii Hlotov)

Animals living near the Akademik Vernadsky Station (photo: Serhiii Hlotov)

Animals living near the Akademik Vernadsky Station (photo: Serhiii Hlotov)

Scientific watch in Antarctica

Our biologists study what helps Antarctic animals and plants survive in such extreme conditions. They observe seals, whales, orcas, leopard seals, and penguins. They monitor how many Weddell seals are born, weighing and measuring them.

For whales, a small piece of skin is taken with a crossbow to study DNA. If it is a female, they determine whether she is pregnant or not. They photograph the dorsal fin and the tail — each tail has a unique pattern, which serves as an individual identifier. These photos are then entered into the global whale atlas.

They also observe bird clutches. Birds build nests in secret locations so that predators cannot find them. They carry mosses and other plants to these places, which may later form new green zones. Scientists are interested in determining whether these plants will spread and where new plantations will appear.

Biologists regularly filter water for phytozoobacteria and plankton. At designated locations, they take water samples, then run them through special systems, preserve them in solutions, and store them in test tubes.

After the expedition is completed, everything is taken home in special Ukrainian repositories. On site, any scientist can contact the repository to take fresh samples and conduct their research.

Biologists also study how crustaceans and other microorganisms manage not to freeze in baths of fresh water that form in rock formations. They also catch fish to determine what parasites they have, observe the dynamics of mosses, lichens, and two species of flowering plants, and study insects that live in these Antarctic mosses.

Periodically, the snow at the station turns green or red because certain algae appear there. Biologists also study this phenomenon: using a drone, they divide the area into squares to calculate the scale of snow algae blooms.

Polar explorers during the expedition (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Ozone hole

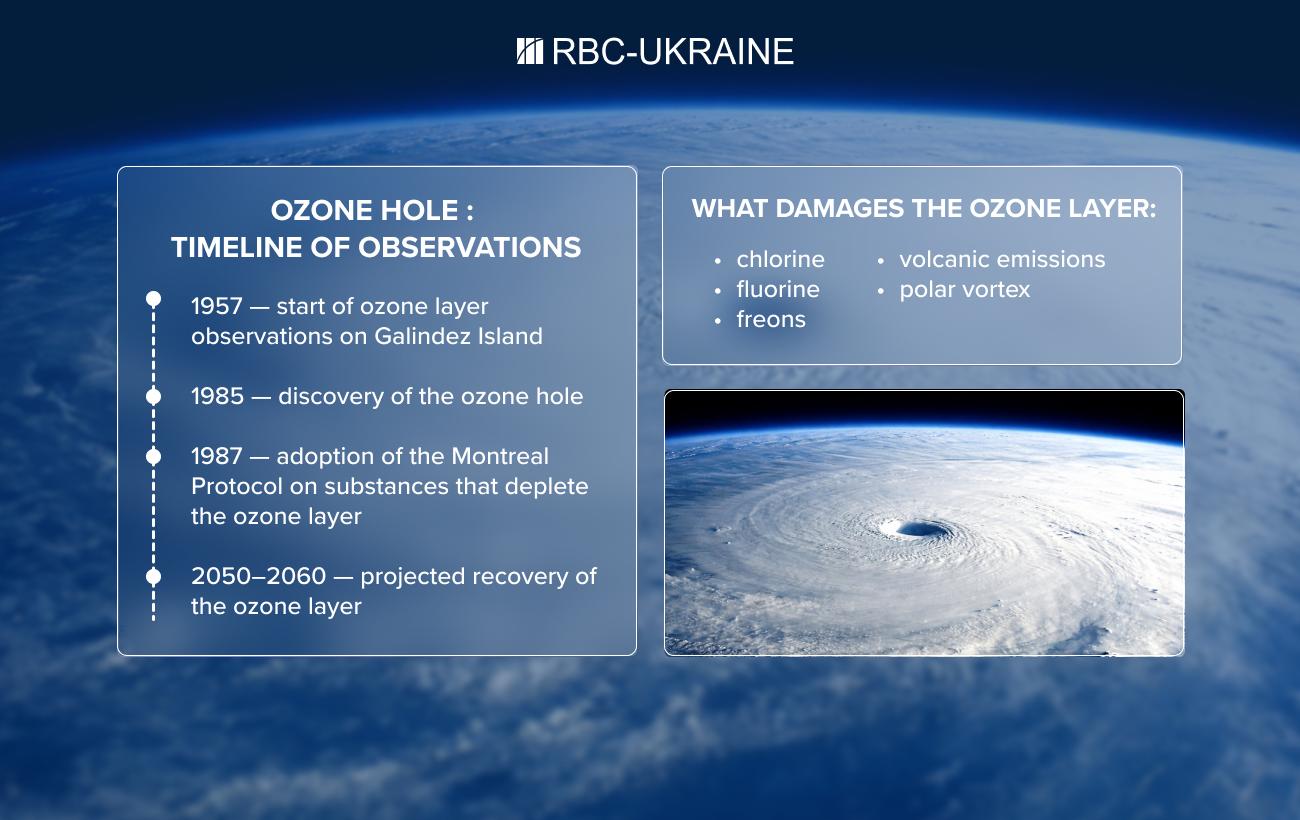

At this station, as well as at the Halley Station, British expeditions began studying the ozone layer in 1957–1958. And in 1985, the ozone hole was recorded here — a phenomenon when the total ozone content in the atmosphere significantly decreases.

We continue observations at the same location; this is exactly what I do. Using a Dobson spectrophotometer, I measure the ozone content in the atmosphere. This is very expensive and extremely precise equipment. There is only one such instrument in Ukraine, and about 100 in the world. We share the obtained data with other scientists. Several other stations also monitor the ozone hole.

If we compare all six of my expeditions, this year the ozone hole period was shorter, and the reduced ozone values were fewer.

Oleksandr Poluden near a device that measures ozone in the atmosphere (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Oleksandr Poluden near a device that measures ozone in the atmosphere (photo provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Ozone is produced under the influence of ultraviolet radiation at the equator, where there is the most sunlight, and then it is distributed across the planet. It self-recovers, but the planet is also capable of destroying it: volcanoes emit various chemical elements into the air, and oceans wash out many minerals.

For example, chlorine, fluorine, and other halogens destroy the ozone layer, but they dissolve well in water. When these substances rise into the atmosphere, they encounter clouds made of water droplets. Under such conditions, a significant part of these compounds is destroyed or changes form before reaching the stratosphere. However, clouds over Antarctica consist not of water droplets but of ice crystals. Under such conditions, chlorine and freons are not destroyed but live for decades, destroying ozone.

There is an entire bouquet of causes that destroy the ozone layer: the spring polar vortex, chlorine, fluorine, various chemical compounds, and freons. Previously, there was a certain balance: the planet destroyed ozone but also restored it. But when humans and the technological revolution came, such substances began to be emitted in much larger quantities. And one chlorine molecule can destroy up to a thousand ozone molecules…

Humanity realized that something was going wrong with the planet, so they created the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. This agreement was signed by all countries. The trend is toward improvement, so by the 2050s–2060s, the ozone hole period over Antarctica should close. However, the ozone layer has decreased not only over Antarctica but across the entire planet. The changes are just more noticeable here.

The ozone hole is not permanent — it can close. This happens when air masses from the ocean, saturated with ozone, enter the region. When a cyclone arrives, pressure drops, clouds and precipitation appear, and along with this comes a new portion of ozone, which increases its level in the region.

In contrast, during anticyclonic, continental weather — when it is clear, sunny, frosty, with high pressure and low humidity — the air contains significantly less ozone.

A season without ice, but with earthquakes

During this expedition, we recorded four earthquakes that were a thousand kilometers away from us in the Drake Passage, south of South America, near Chile and Argentina. Our hydrological station caught a so-called wave, like a tsunami. It was small, but it still reached us. Four earthquakes over such a period are quite a lot. I have not observed this before.

The average temperature of the ocean water in the waters around the Vernadsky Station ranges from –2 to +2 °C. Here, water doesn’t freeze at zero but at –1.9 °C due to a salinity of 32–36‰. Since the water temperature hasn’t dropped low enough, only a small amount of new ice has formed.

And ice for local animals is like a forest: they can hide in it from predators. Also, without ice, they have less space for feeding. Because of this, plants and animals migrate south, look for food bases, enter new locations, and break away from the Antarctic ice shield. This is also a consequence of global warming.

Melting of glaciers

Observations in Antarctica are important for Ukraine, in particular, to understand the consequences of potential climate change. Our country is located in more temperate latitudes. We do not know what tsunamis, storms, hurricanes, or typhoons are. We have optimal temperatures, snow and rain, but when the climate changes, the situation will worsen — there will be more extreme temperature corridors.

If we imagine that Antarctica and all the glaciers on the planet melt, the global ocean will rise by 70 meters. And our Odesa is located at an elevation of 39–36 meters above sea level… Of course, this will affect not only Ukraine but the entire world. Many megacities are located along continental coastlines. A 70-meter rise in the World Ocean means all of this will go underwater.

If such a large amount of fresh water from glaciers enters the World Ocean, it will become desalinated. This will disrupt the living conditions of marine organisms; some species may disappear. And if someone drops out of the biological chain, the rest will have nothing to eat — they will also be at risk because they will have no alternative.

Melting glaciers will lead to a rise in the level of the World Ocean and desalination of its waters (photos provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Melting glaciers will lead to a rise in the level of the World Ocean and desalination of its waters (photos provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Melting glaciers will lead to a rise in the level of the World Ocean and desalination of its waters (photos provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Melting glaciers will lead to a rise in the level of the World Ocean and desalination of its waters (photos provided by the press service of the National Antarctic Scientific Center)

Research of weather, ocean, and space

At the Akademik Vernadsky Station, continuous weather observations are conducted. Meteorologists transmit data every three hours: cloud cover, wind speed and direction, air temperature, atmospheric pressure, precipitation, and meteorological visibility range. Some of this information is encoded into special telegrams — all data must be transmitted on time.

All meteorological stations in the world synchronously, according to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), transmit information about the situation on the planet every three hours. Based on these data, meteorologists see the overall picture — where and what temperature is, wind, cloudiness — and forecast the weather. What we record here in Antarctica is also important for forecasts in Ukraine.

When cyclones approach us and move deeper into the continent, we launch radiosondes — helium-filled balloons with sensors. With their help, we determine the parameters with which these air masses enter. So we can understand how much they warm the continent, because these so-called atmospheric rivers of heat are destroying Antarctica.

We also conduct special hydrological studies. Throughout the year, once a week at designated points, we lower probes into the ocean to a depth of up to 200 meters and observe how the temperature, transparency, and salinity of the water change with depth. This allows us to track processes of desalination and salinization of the ocean in different seasons. We also have a hydrological station that records tides, allowing us to observe how the ocean moves.

World science has already recognized the existence of the fifth — the Southern Ocean. Its boundaries are defined by warm and cold currents around Antarctica. For this, we immerse special Argo floats into the water; they drift, measure temperature at different depths, then surface and transmit data to satellites. We launched six such Argo floats in areas that had not previously been covered by observations.

On our island, there is a glacier 51 meters thick. Using ground-penetrating radar, once a month we scan and track how the glacier changes: how snow accumulates, underground lakes and cracks form.

One of our geophysicists observes near-Earth space and the ionosphere, using an ionosonde. Antennas and observatories around the world transmit signals at different frequencies, which the ionosonde receives. Based on the speed of the signals and their reflection from ionospheric layers, their activity and thunderstorm processes at altitudes of 120–200 kilometers are studied.

The second geophysicist studies the Earth’s magnetosphere, changes in the magnetic field, and auroras. The magnetic field in polar regions is the weakest, so during interaction with the solar wind, we observe green, pink, or purple colors in the sky.

Our robotic systems also record solar activity, and the station has seismoactive pavilions where we register earthquakes.

Our station stands on the front line of world science. We do not have classified data. All collected information is shared with Ukrainian and international institutions so scientists can model, forecast and identify potential risks for the planet.

Among snow, without sun and warmth

Among snow, without sun and warmth