Money in return for reforms? Why the West sets conditions for Ukraine and how it was before Zelenskyy

Photo: Joe Biden and Volodymyr Zelenskyy (GettyImages)

Photo: Joe Biden and Volodymyr Zelenskyy (GettyImages)

Ukraine has started negotiations with the United States and the EU regarding the conditions under which the country will receive grants and loans. For the West, the war itself is no longer a reason to provide money. What reforms donors expect from Ukraine, how they differ from the demands of previous years, and what Zelenskyy's team thinks about it - more details in the editorial material by RBC-Ukraine.

During the preparation of the article, journalists from RBC-Ukraine interviewed current and former officials, diplomats, and politicians familiar with the details of Ukraine's negotiations with Western partners. The information from the websites of the U.S. Department of State, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, the Ministry of Finance, the IMF, and the Verkhovna Rada (Ukraine's Parliament) was used. The following journalists worked on the material: Rostyslav Shapravskyi, Uliana Bezpalko, Milan Lielich, Yurii Doshchatov, and

Every government in Ukraine during a crisis faced a choice - to implement unpopular reforms and receive loans from the West or to bow to the Kremlin. In Moscow, they did not demand reforms; they needed a weak Ukraine ready to pay high political interest for gas discounts. The names of the president and prime minister most often determined the direction - West or Russia. After the Russian aggression in Donbas and the annexation of Crimea, this choice disappeared.

Homework from Washington

A year and a half of full-scale war has exsanguinated the Ukrainian economy. The country has never been as dependent on donors as it is now. According to the Ministry of Finance, since the Russian invasion, the United States, the EU, and other countries have poured over $64 billion into Ukraine's budget. Plus, tens of billions in the form of weapons and military equipment. The leader here is the United States, which allocated nearly $44 billion solely for military support since February 24.

In the West, they remind Ukraine at every opportunity that they will stand with it until victory, at least until Ukrainians themselves decide that it has already come. However, the longer the war lasts, the less reason the US and the EU have to give money to the Ukrainian government without obligations. Partners' demands are becoming tougher, and the tone of the conversation is sometimes sharper. Ukraine itself provides grounds for louder criticism in the West due to high-profile corruption scandals in army procurement and the idea of shifting anti-corruption bodies away from the actual fight against corruption. More on this here.

The start of the presidential race in the United States and their domestic political landscape, against the backdrop of criticism that Biden is spending too much on a war in distant Europe, also do not play in favor of Ukrainians. The recent events in Congress with the vote on the defense budget, where there was no place for Ukraine yet, confirm this.

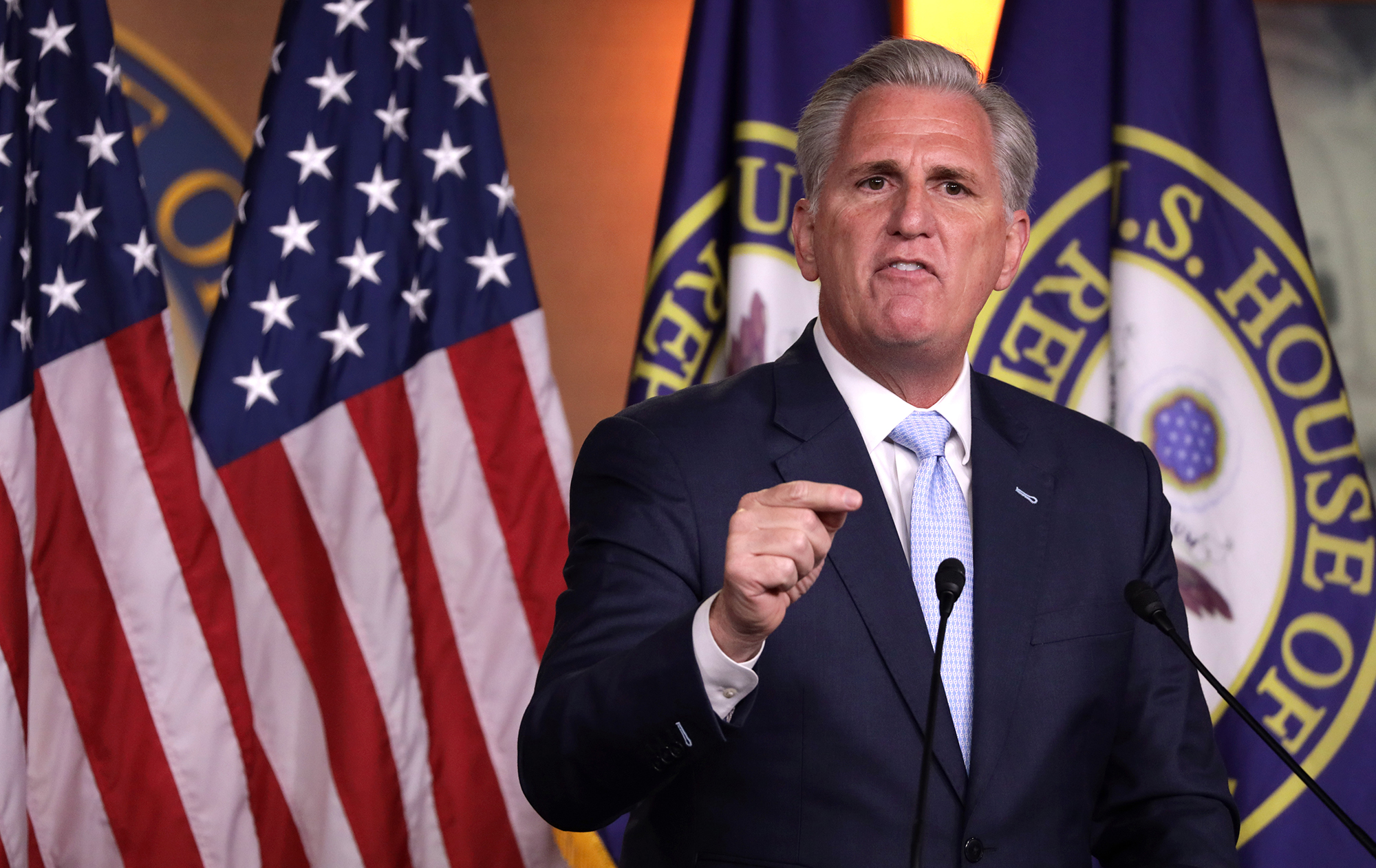

Kevin McCarthy, Republican U.S. House of Representatives speaker (Photo: Getty Images)

A few months ago, RBC-Ukraine's sources in the Ukrainian government talked about donors tightening the screws on money matters. In the United States, for example, the September tranche of $1.25 billion to the budget was directly linked to the submission to the Ukrainian Parliament of a bill to strengthen the powers of the Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office and its head.

The principle of "did it - got it" or "money in return for reforms" may become fundamental. For some time now, the government has been negotiating with donors on unifying the terms with a clear schedule for their implementation. Moreover, Ukraine has already undertaken several commitments to its partners, such as the IMF or the EU macro-financial assistance agreement, and so on. Now the task is to bring all this into a single logic.

"It's like in a company: you're the boss, your subordinate writes everything on pieces of paper, and then it turns out that he lost one piece of paper, but, he says, he completed two tasks. So you need to create a summary of all Western demands," explains a source from the president's entourage.

A reform plan was supposed to be developed on a donor platform in Brussels. But on the eve of its last meeting last Tuesday, the media published a list of reforms prepared by the American side - from the anti-corruption block, and the judicial branch to economic policy, including privatization, corporate reform, and tariff liberalization.

The appearance of such a draft was perceived by many as the demands of Big Brother, which did not add constructiveness to the negotiations. The next day, the American Embassy even issued an official position on the reform package, and a few days later, Ambassador Bridget Brink handed a list of recommendations to Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal.

Ambassador Bridget Brink and Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal (Photo: press service of the Prime Minister)

"It might be assumed that Americans are imposing conditions on us, and we unquestionably have to fulfill them. But that's not the case. Our partners are asking us what we can do and what we cannot. All the reforms have long been discussed, and we are initiating some of them ourselves. And it's important that in this process, there are also the EU and other countries, not just the USA," says a source in government circles.

However, officials acknowledge that all Western proposals for reforms eventually become laws sooner or later. "There's nothing unusual here – we've received money under specific conditions before. Of course, we can discuss the terms or some details, but essentially, everything remains as the partners propose," notes one of the Servant of the People deputies.

Almost all interviewed politicians and government representatives agree that the biggest challenge of the reform package will be the demands related to anti-corruption. This block is directly tied to Ukraine's European integration.

"The deputies have not yet digested the opening of declarations, which will soon manifest in practice: a bunch of various infographics like 'Who has enriched the most during the war,' investigations, and more. And ahead is the story with PEPs (referring to lifelong monitoring of PEPs and the creation of a register)," says a representative of the Servant of the People party.

In his opinion, if the deputies "swallow the PEP cactus," they won't be ready to vote for any anti-corruption stories regarding NABU (National Anti-Corruption Bureau) and SAP (Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office).

Much will depend on the mood at the President's Office. Negotiations are already underway at the level of the Bankova (President's Office) and anti-corruption bodies regarding a series of initiatives, such as increasing NABU's staff to 300 individuals, establishing an expert center within the Bureau (which the President's Office has not yet agreed to) and expanding NABU's powers for wiretapping.

"As a separate point, the U.S. has emphasized the independence of NABU as an investigative body in its recommendations. And here it can be argued that this line appeared in response to the proposal of the President's Office to take some cases from the Bureau and transfer them to the Security Service of Ukraine, calling them state betrayal," one of the sources remarks.

Yaroslav Yurchyshyn, Deputy Chairman of the Anti-Corruption Committee of the Verkhovna Rada, sees nothing new in the U.S. demands, calling them an expanded list of IMF conditions. And although they will still be discussed with all donors, he is confident that there should be no fundamental changes in the fight against corruption.

"They haven't asked us to do anything impossible. The law on SAP is ready and in parliament, the bill regarding increasing NABU's staff is also ready. As for the establishment of an expert body, there will be discussions with donors," explains the deputy.

The issue also lies in time. There isn't much time to iron out the details and agree on the final list of reforms and the financing format. Ukraine itself is interested in doing this as quickly as possible. The EU's program for €50 billion (the so-called Ukraine Facility) is set to begin in 2024, running until 2027. According to RBC-Ukraine, the government expects to receive the majority of this amount next year, understanding the unclear prospects of U.S. funding.

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen and President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy (Photo: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

"The USA wants the EU to give us more money, but Europeans don't want to. The amount of aid for next year is still not guaranteed, although guarantees were already in place by this time last year," notes one of the deputy sources.

In his opinion, only at the beginning of next year will we receive a similar list of reforms from the European Union – precisely when negotiations on membership open. "And the first demand on the list will be judicial reform and anti-corruption," he adds.

From Tymoshenko to Groysman. Bargaining with the West is inappropriate

At various times, Ukraine sought assistance from the West, agreed to the conditions of creditors, and ceased to comply with them as soon as the economy showed signs of improvement. Most of the support came from the International Monetary Fund, where the United States played a significant role. However, this usually occurred during relatively peaceful times for the country.

The Fund helped the government of Yuliia Tymoshenko during her tenure, which coincided with the global financial crisis. In 2008-2009, the Cabinet of Ministers received three tranches from the IMF, totaling nearly $11 billion, which prevented a complete collapse of the hryvnia exchange rate, allowed for debt repayment, and covered a portion of budget expenditures.

In pursuing reforms, the government promised the IMF to gradually raise utility tariffs for the population and the price of gas, without compensating for the price difference from the budget. However, there was no mention of anti-corruption conditions in that program, according to Serhii Vlasenko, a member of the Batkivshchyna (Homeland) party.

"If you look at all the memorandums with the IMF signed during Tymoshenko's premiership, there was not a word about fighting corruption. But now it's almost the number one point. And if earlier, from 2007 to 2009, they simply needed guarantees of loan repayment, so they focused on balanced economic indicators, now they need guarantees that these funds will not be embezzled," reflects a comrade of the Batkivshchyna party leader.

Leader of the Batkivshchyna party Yuliia Tymoshenko (Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

Leader of the Batkivshchyna party Yuliia Tymoshenko (Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

Shortly before the presidential elections, Tymoshenko postponed the increase in gas tariffs, predictably scheduling the price hike after the vote. However, she lost the election to Viktor Yanukovych. Even without the increase in tariffs, the situation in the country left much to be desired. Problems in the country due to the swine flu, gas contracts with Putin, and hindrances from President Viktor Yushchenko obstructed Tymoshenko's path to the presidential seat.

The government of Mykola Azarov and former President Viktor Yanukovych also sought help from the IMF and prepared to assume the role of the main Euro-integrators. A critical moment occurred at the end of 2013 when Azarov publicly accused the IMF of demanding harsh measures, such as tariff increases, freezing social standards, and other unpopular measures. "There are other possibilities besides the IMF," commented the prime minister, understanding that Yanukovych had already negotiated a $15 billion loan and a gas discount with Putin.

As a result of the agreement with the Kremlin, Yanukovych refused to sign the EU Association Agreement. The conditions presented by the EU, as the future fugitive president claimed, were not in Ukraine's favor, so it was supposedly worth waiting for a better deal. "What kind of agreement is it when they take us and 'bend' us?" said the former president.

Yanukovych, trying to sit on two chairs, initially did not reject the European integration path, where Ukraine faced a difficult road of democratic reforms, and at the same time, he watched the reaction of the U.S. and the EU, scaring the West with possible rapprochement with Russia, which did not promise anything good for Ukraine.

"The West's conditions have always been unpopular. But they always depended on the economic situation in the country. When things were bad, the pressure was stronger. The West's basic philosophy: reforms at the expense of the population or state reserves," says one of the political figures of Yanukovych's era in conversation with RBC-Ukraine.

For the former president, the question was only about how to get the money and remain popular in the eyes of the electorate. By betting on Russia and losing everything, Yanukovych triggered a crisis, Russian aggression began, and Moscow ceased to be an alternative donor for Ukraine.

Former president Viktor Yanukovych (Photo: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

After Yanukovych fled, a new phase of relations with the U.S. and the EU began under the leadership of Prime Minister Arsenii Yatsenyuk and President Petro Poroshenko. The government immediately reached an agreement on a new comprehensive program with the IMF, simultaneously borrowing under guarantees from the U.S. and the EU.

Yatsenyuk, while trying to stabilize the economy under the control of partners, had to make unpopular decisions, including revising tariffs and freezing social and budgetary payments. Later, a former prime minister's ally and Speaker of the Parliament, Oleksandr Turchynov, mentioned that their reforms had damaged the popularity of their party People's Front. Despite winning the elections in October 2014 with over 22% support, the People's Front's rating dropped below 1% within a year.

After resigning in April 2016, Yatsenyuk did not return to active politics. His attempt to shift the decision to increase tariffs onto the new prime minister, Volodymyr Groysman, before leaving the Cabinet, did not save his political career. By the way, Groysman's political force did not make it to the parliament in the 2019 elections, leaving the former mayor of Vinnytsia outside of political life for at least four years.

The block of anti-corruption reforms, linked to European integration, including visa-free travel with the EU, did not bring political dividends to Yatsenyuk either, as it was challenging to overshadow the overall negative sentiment. However, the process initiated at that time remains crucial in Ukraine's relations with the West.

Arsenii Yatsenyuk, Volodymyr Groysman, Oleksandr Turchynov, and Arsen Avakov can no longer find their place in Ukrainian politics (Photo: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

Partners who increased financial support to Ukraine since 2014 had a vital interest in ensuring the preservation of funds and their targeted use. Since then, infrastructure for the National Anti-Corruption Bureau, Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office, the National Agency on Corruption Prevention, and later the High Anti-Corruption Court was established under the supervision of the U.S. and the EU. Ukraine, despite its challenges, introduced electronic declarations, disclosing the incomes of officials and politicians.

Anti-corruption requirements were bundled with economic ones, recalls one of the officials during Poroshenko's presidency. However, according to him, most of the conditions were not initiated by the Americans but rather proposed by Ukrainian anti-corruption activists and advocates who shared their insights with the Department of State.

"That was the case for most of the topics that later went into various agreements. For example, there is no lifelong declaration for the PEPs in the U.S. They told us that the requirement for public declaration was not initially on their minds. Personal privacy is a serious issue in America. At some point, they said, 'Guys, you've gone too far.' The Europeans said the same," says the source.

Negotiating and persuading partners was possible on economic matters, says Nina Yuzhanina, a deputy from the European Solidarity party, who chaired the parliamentary tax committee during Poroshenko's presidency. According to her, the IMF imposed a strict condition between 2014 and 2016 – to eliminate the simplified taxation system, which the Fund regarded as nothing more than an internal offshore.

"We were offered to keep only the first group – these are people who, roughly speaking, trade somewhere in small markets and engage in very small-scale trading. However, we managed to reach a compromise at that time," says Yuzhanina. She immediately admits that the government team failed to persuade the Fund of the need to introduce a tax on repatriated capital – their arguments fell on deaf ears.

The Americans also showed their character when Petro Poroshenko refused to corporatize the defense industry. According to a top government official of those times, in 2016, Ukraine and the U.S. planned to start significant cooperation in the defense industry. From the American side, Joseph Biden, in his position as vice president, was in charge of this topic.

"But Poroshenko vetoed the law on supervisory boards concerning military enterprises. The Americans said that if there were no supervisory boards at defense enterprises, there could be no talk of any cooperation in this area," recalls the source. In his opinion, had Ukraine carried out this reform properly, the countries could have achieved more in military cooperation long ago.

The issue of corporatization remains relevant to this day. However, it no longer concerns the military but rather energy companies, where processes are moving quite slowly. Supervisory boards have not been established everywhere, as in the case of Naftogaz (the largest national oil and gas company in Ukraine). The reform of Gas Transmission System Operator of Ukraine management is dragging on, and the transformation of Energoatom (national nuclear energy generating company) into a joint-stock company should be completed by next March at the latest, but there is no certainty that everything will go according to schedule.

Petro Poroshenko in the Parliament, 2019 (Photo: flickr.com)

Surviving the storm with the help of Western loans, Poroshenko's team gradually began to slow down the pace of reforms, and some even tried to reshape them in their favor. At the end of 2017, the coalition of the Bloc of Petro Poroshenko and the People's Front decided to reduce the powers of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office by proposing a draft law that would allow the Rada to dismiss the heads of these bodies and any member of the National Agency on Corruption Prevention and the director of the State Bureau of Investigation at its discretion. The attempt to make anti-corruption structures politically dependent did not work out. Probably, Western donors did not appreciate such a move, neither before nor after these events. U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said at the time that "it serves no purpose for Ukraine to fight for its body in Donbas if it loses its soul to corruption."

In the EU, upon seeing the draft law, they were on the verge of canceling visa-free travel and suspending all financing programs. The IMF also demanded that the authorities stop pressuring anti-corruption agencies and accelerate the establishment of the High Anti-Corruption Court, which was one of the conditions for Ukraine's financing. Under unprecedented Western pressure, the government could not withstand and did not bring the idea to its conclusion.

In 2020, President Zelenskyy's team experienced the West's displeasure when the Constitutional Court stripped the National Agency on Corruption Prevention of its main powers and removed criminal liability for inaccurate declarations. The European Commission again pointed out the risks of canceling visa-free travel. Former President Poroshenko, criticizing both the new government and the Constitutional Court, promised to "defend visa-free travel," which he nearly buried a few years earlier. By the way, within two months, the President's Office and the Rada restored the e-declaration and returned the powers to the National Agency on Corruption Prevention.

***

Every time Ukraine turned to the West for help, it asked for fish, not a fishing rod. The main goal of every government was money, not reforms and structural changes in the country. Recognizing this, international donors started prescribing anti-corruption pills to the Ukrainian government in their recipes for economic rescue, forcing the patient to take them.

The big war with Russia changed everything. The survival of the country and its economy now directly depends on external donors. However, their demands are not as stringent in terms of potential social tension as they were 5-10 years ago. Even the conditions for tariff liberalization don't seem as problematic as before the start of energy reforms. The same anti-corruption initiatives are unlikely to be perceived negatively by society; the only ones who might block them are political elites who see elements of external control in them.

President Zelenskyy, unlike his predecessors, cannot hang the failure of reforms on a confrontational prime minister, a disobedient parliamentary coalition, or an opposition revolt, as his predecessors did. His approval rating and de facto absolute power, which a head of state has during a war, allow him to push through even more unpopular reforms if the partners insist on them.

By rejecting conspiracy theories about external control, it is worth accepting reality and finally seeing the window of opportunities, even if circumstances are pushing us toward it. For now, the West and the United States in particular, by presenting their vision of changes in the country, have sent a positive signal that they believe in Ukraine and see the sense in its reform. "This is a humanistic pedagogy, raising difficult children through occupational therapy," one Ukrainian politician ironically says.