High stakes: Who will win the Polish elections and what Ukraine should expect

Photo: President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy and President of Poland Andrzej Duda (Getty Images)

Photo: President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy and President of Poland Andrzej Duda (Getty Images)

On October 15 Poles are electing both chambers of their parliament. How the election campaign in Poland went and what coalition could be formed after the elections, why mutual insults have become a common style in Polish politics, and whether relations between Warsaw and Kyiv will improve – more details in the material from RBC-Ukraine.

Materials from POLITICO, Business Insider, Financial Times, Foreign Policy, Gazeta Wyborcza, and other Polish and international media, as well as off-record comments from informed sources from Poland, were used during the preparation of the material.

This Sunday the next foreign elections will take place, which have significant importance for Ukraine. The recent parliamentary elections in Europe, which took place in Slovakia two weeks ago ended with the worst result for Ukraine - an anti-Ukrainian coalition led by former Prime Minister Robert Fico was formed. With a high probability, Ukraine has gained another problematic country on its western border, alongside Hungary.

There is some, albeit small, risk of something similar happening after the Polish elections, although in general, Poland will likely remain in the pro-Ukrainian Western coalition. But, at the very least, tensions regarding Ukraine may not completely dissipate even after the elections. In any case, the "honeymoon" between Kyiv and Warsaw, which lasted from last winter until approximately this summer, is unlikely to be repeated.

"Fools" vs. "Enemies of the people"

Since 2015, Poland has been governed by the conservative party Law and Justice (PiS), which holds a majority in the lower house of parliament, the Sejm. The country's president, Andrzej Duda, is also affiliated with PiS.

Currently, according to polls, PiS is likely to finish first again, with an average rating of 37% according to the POLITICO poll aggregator. However, for obtaining an outright majority for the third consecutive time (in post-communist Poland, no party has been in power for more than two terms), this might not be sufficient.

In second place are their main opponents from the center-right Civic Coalition (CC), led by former Prime Minister and former President of the European Council, Donald Tusk. Their average rating is 30%.

Three more parties are likely to enter the parliament: the centrist bloc Third Way (11%), the coalition of left-wing parties, and the far-right Confederation (both at 10%).

In terms of intensity, Polish parliamentary races do not yield even the best Ukrainian examples. The two main parties, PiS and CC, depicted each other not just as political competitors but as true enemies, concentrating all possible evils in Polish politics.

Among notable scandals were investigations into the issuance of hundreds of thousands of visas for migrants from Asia and Africa in exchange for bribes at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the disclosure of maps of Poland's defense strategy from 2011 (at that time, under Tusk's government, it was planned to retreat all the way to the Vistula in the event of a Russian invasion); and the high-profile dismissal of prominent Polish generals due to their disagreement with the Ministry of Defense's actions just before the elections.

There was also room for typical pre-election tactics. For instance, at the ruling party's initiative, a referendum will take place parallel to the elections, in which Poles will be asked about the sale of state property to foreigners, the retirement age, the wall on the Belarusian border, and the admission of migrants to the country. Therefore, PiS apparently aims to increase voter turnout among its supporters, as is often the case with the supporters of a long-ruling party, who are generally less eager to go to the polls than opposition sympathizers.

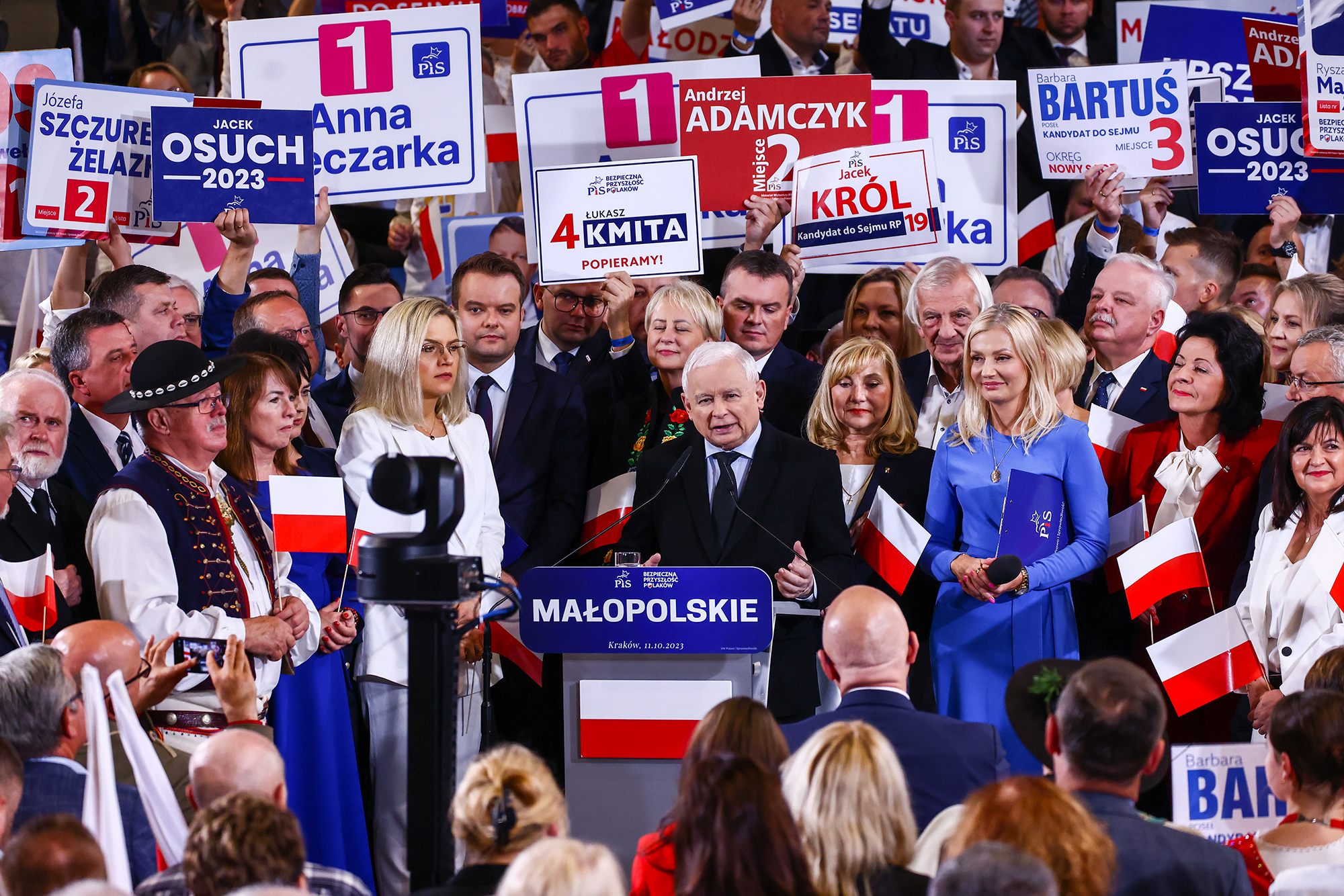

Leader of Law and Justice Jaroslaw Kaczynski at a rally (Photo: Getty Images)

The campaign was intensified by the fact that Polish politics is highly personalized. Essentially, for many years, it has revolved around two figures: Donald Tusk and the leader of PiS, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, who also currently holds the position of deputy prime minister (he is usually referred to as the most influential person in Poland). Their relationship has had the character of not just political competition but open personal enmity for almost two decades.

In 2005, PiS accused Tusk of having a grandfather who fought in the Wehrmacht. During the next campaign, Tusk played a trick on Kaczynski during a televised debate by catching him off guard about the prices of potatoes in stores - this story deeply offended the PiS leader. He believes Tusk is implicated in the Smolensk plane crash of 2010, in which his twin brother, then-Polish President Lech Kaczynski, perished.

During the current campaign, exchanges of accusations and insults continued. Tusk was reminded that his grandmother was an ethnic German, and the leader of CC mocked Kaczynski for being a bachelor at the age of 74 (while emphasizing the importance of traditional family and family values).

The televised debates that took place this week were also indicative. Instead of Kaczynski, PiS was represented by Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki (Tusk immediately accused Kaczynski of cowardice). During the debates, Tusk called Morawiecki "Pinocchio" (apparently, referring to the premier's resemblance to the character), and Morawiecki ridiculed his opponent's red hair. "The 'Red' gang" - this is how Kaczynski and his allies constantly refer to their opponents.

Harsh accusations were also frequent. Kaczynski branded Tusk as the "enemy of the Polish people," and Tusk called the ruling party's team "agents or fools." PiS released videos where Tusk spoke German (purportedly as proof that he's a German agent). CC released videos with a compilation of Kaczynski's failed performances under the slogan "Do you want HIM to rule you?"

Mutual insults and trolling, which often descend into outright primitivism, reflect a deeper ideological divide between the two key Polish parties. PiS consistently emphasizes the importance of Poland's sovereignty and opposes the "Brussels dictatorship" in Poland's internal affairs. In the West, it has been publicly discussed for many years that, during PiS's rule, Poland has noticeably degraded in terms of democratic values, especially the independence of the judiciary and the media. This has even led to the freezing of billions of euros in EU assistance that Poland was supposed to receive. In response, the ruling party argues against EU interference in Poland's internal affairs.

In the event of coming to power, Tusk promises to restore relations with Brussels and to revoke the most controversial decisions of the conservatives, such as the de facto ban on abortions.

Both sides constantly veer to extremes in their arguments. PiS portrays Tusk as a submissive puppet of Brussels and, especially, Berlin, who obediently follows any instructions from the German embassy. In response, Tusk accuses the current government of having a secret plan for Poland to leave the EU (despite the PiS's Euroskepticism, EU membership is supported by the vast majority of Poles and is beneficial to the country at least from an economic point of view).

The constant references to Tusk's German connections and his ancestors (one sympathetic journal even depicted him on the cover as Hitler) are not accidental. Last year, Warsaw even presented a claim of 1.3 trillion euros in reparations for World War II to Berlin. But if this can be seen as a classic populist maneuver, the essence of PiS's claims against the Germans is much deeper.

The leader of Civic Coalition Donald Tusk (Photo: Getty Images)

The current Polish government believes that Germany, along with France, has taken an absolutely dominant role in the European Union and is pursuing the bloc's policies in its own interests, to the detriment of other countries, including Poland. Warsaw views with great concern the idea of an internal EU reform, under which many decisions will be made not by consensus but by a qualified majority of votes. As a counterbalance to the German-French bloc, many in the Polish government see an alliance with Ukraine.

Three scenarios

Overall, the Ukrainian issue occupied a noticeable, although not central, place in the campaign. Polish sources provided the following figures: 60% of the campaign revolved around socio-economic issues, while the remaining 40% pertained to foreign policy, which included not only Ukraine but also Brussels and Berlin.

However, as the elections approached, it significantly influenced Ukrainian-Polish relations. The conflict over the import of Ukrainian grain, essentially an economic dispute, quickly escalated due to the efforts of Polish politicians and became more global concerning relations with Ukraine as a whole. Of course, Kyiv's role in escalating the conflict is also evident, at least in terms of sharp rhetoric. President Zelenskyy's speech at the UN General Assembly implied that Poland's actions in the grain crisis were benefiting Moscow, deeply offended Poles, and led to accusations of ingratitude, considering Poland's historic and ongoing role in supporting Ukraine in the West. Additionally, within the Law and Justice Party, there is a prevalent belief that the Ukrainian government entered into a secret conspiracy with the Germans to overthrow PiS and bring the Civic Coalition to power.

Undoubtedly, as Ukraine draws closer to the EU, conflicts like the grain dispute will continue to arise, as Kyiv and Warsaw are direct competitors in many economic sectors. Nevertheless, Poland unequivocally stands on Ukraine's side. According to one RBC-Ukraine source, if Kyiv ever considers a peace agreement with Russia, the current Polish government will staunchly defend Ukrainian interests. However, in the event of a government change in Warsaw, it might be more accommodating to the "peaceful" Germans.

It's evident that the tension between Poland and Ukraine has eased over the last few weeks, at least in terms of rhetoric. The conclusion of the elections is expected to solidify this trend. However, much depends on the election outcome, and there are several possible scenarios.

The first scenario involves PiS achieving a good result but falling just short of an absolute majority. This is quite possible if we assume that pre-election polls are not entirely accurate and don't account for "shy voters" who, especially in major cities, don't want to admit their support for the ruling party to pollsters. In such a case, PiS might try to secure the missing mandates through individual agreements with other factions, a practice acceptable both in Poland and Ukraine. In this scenario, Warsaw's current policy toward Ukraine will likely continue, with some adjustments, and more emphasis on protecting Polish national interests.

Supporters of PiS watch Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki's performance at the debates (Photo: Getty Images)

The second scenario is the formation of a coalition involving the Civic Coalition, the Third Way, and left-wing parties. This alliance would be ideologically loose, and many leaders of these parties have complex personal relationships. However, they are all generally pro-Ukrainian. At least Donald Tusk, who would probably return to the Prime Minister's seat in such a case, has already presented a vague four-point plan for normalizing relations with Ukraine. This coalition would also have to advocate for the interests of Polish agrarians, as the Polish Peasants' Party is part of the Third Way and considers this a key issue on the agenda. However, for this scenario to become a reality, the Third Way would first need to pass the parliamentary threshold; some recent polls show it with less than 8%, which is the minimum required for election coalitions.

Finally, the third scenario is the most potentially dangerous for Ukraine: the formation of a coalition between PiS and the far-right Confederation party, which openly opposes assistance to Ukraine. Like PiS, Confederation could perform better than indicated by pre-election polls, due to the "shy voter" effect. A few years ago, the eccentric leader of Confederation, Sławomir Mentzen, described their program as, "We don't want Jews, homosexuals, abortion, taxes and the European Union." Currently, the party is trying to appear more respectable, with its leaders focusing on economic issues rather than discussing Jews. The main intrigue is whether Confederation would agree to join an alliance with PiS or the Civic Coalition if necessary (although this option is not particularly realistic). The party's leadership insists they will remain in opposition, but in Polish politics, post-election promises are often adjusted. In this case, even if Confederation is the junior partner in the coalition, Warsaw's overall course may lean in an anti-Ukrainian direction.

However, there is also a possibility that no agreement can be reached for any coalition scenario, and Poles will have to go to the polls again early next year. "We will somehow survive this; it's not a big deal. But for you, it will be bad news: all those involved in assisting Ukraine will sit and wait to see how it all turns out," said one of the Polish sources to RBC-Ukraine.