Elections after war? How Ukraine preparing to vote and hurdles ahead

Volodymyr Zelenskyy and voting in the elections (collage by RBC-Ukraine)

Volodymyr Zelenskyy and voting in the elections (collage by RBC-Ukraine)

The war is far from over, but preparations for the upcoming elections are underway in Ukraine. Read the RBC-Ukraine article to learn about the main challenges to holding the elections, how the authorities plan to address them, and whether the experience of other countries will be useful in this regard.

Key points:

- Elections only after the war: President Zelenskyy and the Central Election Commission emphasize that voting is only possible after the end of hostilities.

- Transition period: The Central Election Commission proposes at least six months to prepare for the election campaign.

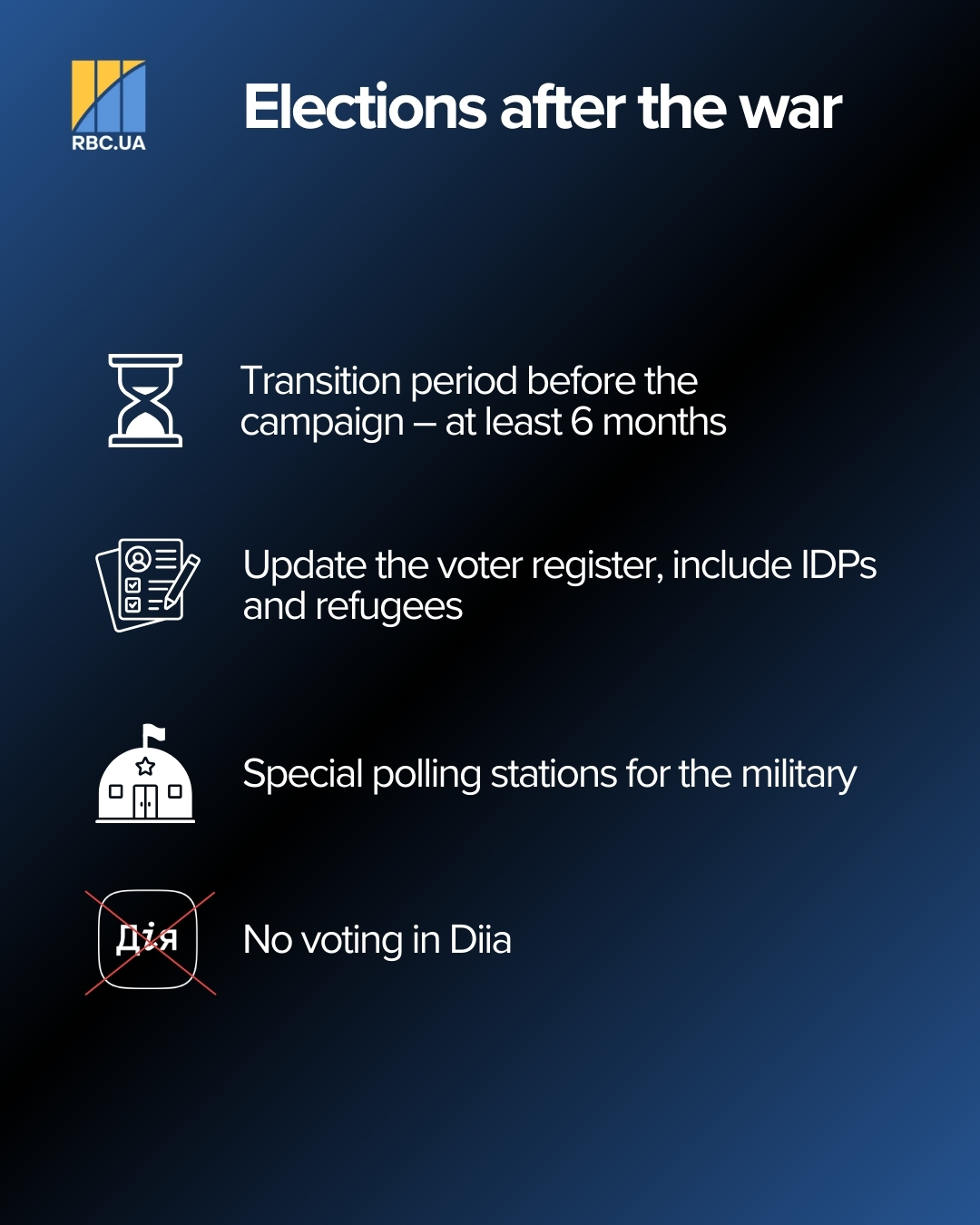

- Internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees: The main challenges are to find where voters are and ensure they can vote.

- Infrastructure and polling stations: Most rear polling stations are in good condition; 20-25% are damaged in frontline areas.

- Voting abroad: More polling stations; no plans for electronic voting yet.

- Voting by military personnel: At special polling stations or at the location of the unit; the political neutrality of the Armed Forces of Ukraine is important.

"I am now asking, and I am saying this openly, for the US to help me, possibly together with our European colleagues, to ensure security for the elections. Then Ukraine will be ready in the next 60-90 days," President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said on December 9.

The topic of holding elections in Ukraine has long been raised by some Western partners, mainly Americans. Therefore, the elections are no longer purely an internal issue and have returned to the agenda along with the war and negotiations to end it.

At the same time, according to RBC-Ukraine's sources in the government, Zelenskyy's statements about the elections at this particular moment are not related to any specific plans to hold a vote. Instead, they were a reaction to US President Donald Trump's latest accusations that Ukraine has not held elections for a long time.

The Ukrainian message is simple: elections are only possible after the end of hostilities. But regardless of the motives, the process has been set in motion. And here a dilemma arises: what should the first post-war expression of will be? And is Ukraine ready for it, not only formally, but also in essence?

The Central Election Commission (CEC) proposes to establish a transition period after the end of the war, lasting at least six months before the start of the election campaign.

However, even under such basic conditions, there is no universal scenario for Ukraine. Deputy Chairman of the CEC Serhii Dubovyk said in an interview with RBC-Ukraine that the commission had studied a large amount of foreign experience, but none of it could be mechanically applied to Ukrainian realities.

"First of all, it is the size of our country, the size of the electoral infrastructure and the number of voters, and our country's location within the family of European nations," Dubovyk explains.

At the same time, certain examples are still worth considering — at least to avoid repeating old mistakes in the context of the post-war restart of the political system.

How to find voters

During the years of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, millions of Ukrainians became refugees, either by moving abroad or becoming internally displaced persons by simply moving to another region of Ukraine.

In the context of elections, this poses two problems. The first concerns the infrastructure for voting. The second is the need to understand where voters are located and allow them to vote.

Bosnia and Herzegovina faced similar difficulties in 1996 after the end of a bloody civil war that lasted four years. There, the issue of refugee and IDP participation in elections was resolved as part of a broader peace process, explained Samir Ibisevic, a public figure from Bosnia and Herzegovina, to RBC-Ukraine.

"The first post-war elections were held only after the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement, which not only ended the war but also introduced a new constitutional and administrative-territorial model of the state," Ibisevic says.

After that, electoral districts were formed, electoral commissions were created, and voter lists were confirmed, including refugees and internally displaced persons.

Only when the conflict was formally ended, with a clear legal framework in place, was it possible to hold the first post-war elections.

"International institutions played a significant role in this process, ensuring oversight of voter registration and the legitimacy of the electoral process," Ibisevic emphasizes.

.jpg) Number of Ukrainian refugees and internally displaced persons (Infographic RBC-Ukraine)

Number of Ukrainian refugees and internally displaced persons (Infographic RBC-Ukraine)

Similar challenges arose in Iraq in 2005, after the US invasion and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein's regime. The elections took place in conditions of de facto low-intensity warfare, terrorist attacks, and mass internal displacement of the population.

For the first time, voting was organized in 14 countries for Iraqi refugees abroad. However, the participation of IDPs within the country remained fragmented and uneven, which was later criticized by international observers.

As noted in a Brookings Institution report, internally displaced persons faced several practical obstacles.

American analysts Balkees Jarrah and Erin Mooney wrote that many were unable to register before the deadline, and some lost their documents due to flight or the destruction of their homes.

Will there be electronic voting?

Unlike Bosnia and Herzegovina and Iraq, Ukraine still has a functioning Central Election Commission. So it is clear how to solve the problems of voting for IDPs and refugees in general. According to Serhii Dubovyk, the electoral infrastructure within Ukraine is relatively good.

In the rear regions, most of the buildings used as polling stations remain intact. In the frontline territory, about 20-25% of polling stations are located in damaged buildings, but this is not fatal, according to the deputy head of the CEC.

"It's a little more difficult now, but we are also considering using small architectural forms for polling stations, organizing them in temporary structures," Dubovyk tells RBC-Ukraine.

As for Ukrainians voting abroad, the only real solution is to expand the network of polling stations, as agreed with each country. However, the CEC proposes to separately enshrine in law that elections will not be held on the territory of Russia and Belarus.

At the same time, voting in Diia is not yet being considered as a real option. At the very least, there is no legislative framework for this.

"At the moment, apart from some online discussion, no work is being done in this area. Neither the Ministry of Digital Transformation nor the app team is working on the implementation of such a tool," said Mykhailo Fedorov, then Minister of Digital Transformation, on December 29.

In general, voting by refugees and IDPs will be the least of all possible problems, Andrii Mahera, deputy head of the Central Election Commission in 2007-2018 and a constitutional law expert at the Center for Political and Legal Reforms, says in a comment to RBC-Ukraine.

"In parliamentary and presidential elections, it does not matter where such voters will vote. Because their votes go into the same pot, within the entire country. It does not matter where they vote for one party or another," Mahera says.

According to him, IDPs and refugees can be included in the voter list after changing their electoral address.

"The legislator must provide safeguards to ensure that this electoral address does not change too often. To prevent electoral tourism. For example, to retain the right to change the electoral address once a year," the expert stresses.

However, the only realistic option in this case would be to return to a proportional model, where the Rada is elected solely from party lists without majority candidates.

However, all this is still under discussion within the working group on the preparation of updated electoral legislation. At the end of December last year, it was created in the Verkhovna Rada on the instructions of Zelenskyy. In addition to people's deputies, it includes representatives of the government and civil society.

The work is being carried out in seven areas: from the administration and security of elections to voting by IDPs, refugees, and military personnel, as well as the fulfillment of Ukraine's international obligations in the field of elections. According to Davyd Arakhamia, head of the Servant of the People faction in the Verkhovna Rada, a specific bill should be drafted by the end of February.

For now, the working group's online meetings are being used to test drive a wide variety of ideas regarding the elections, on which not only government officials and experts, but also experts themselves, cannot agree.

In general, the key issue is updating the state voter registry, says Oleksandr Kornienko, first deputy speaker of the Verkhovna Rada and head of the working group, in an interview with RBC-Ukraine.

"First and foremost, we are talking about updating the mechanisms for filling the state voter registry voluntarily, using electronic technologies for this purpose, and extending the deadlines for such self-registration," Kornienko explains.

The working group is considering integrating the electronic voter's office with Diia and geotracking services. This should also help with finding the nearest polling station.

Voting by military personnel

Another challenge for Ukraine will be the participation of those in the Armed Forces in the elections. They can be included in the voter lists where the military unit is located. When troops are deployed in the field, as an exception, a special polling station can be created at the request of the Ministry of Defense.

"The only thing is that the creation of special polling stations should not be abused, because there is much less publicity there than at regular polling stations," Mahera notes.

According to Kornienko, it may be difficult for military personnel in the Ukrainian Defense Forces to exercise their right to be elected. This will be particularly relevant during parliamentary and local elections, when thousands of military personnel will express their desire to become deputies at various levels.

In post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina, there were no special or separate voting mechanisms for military personnel. Military personnel had the right to vote and participated in elections on an equal basis with other citizens in accordance with the applicable electoral law.

"At the same time, there was a clear restriction on the participation of military personnel in political activities as candidates. Military personnel could not run for elected office while in service," Samir Ibisevic tells the agency.

To participate in elections, they had to resign from military service. The essence of this restriction was to ensure that the armed forces remained politically neutral.

"This approach was aimed at preventing the militarization of politics and reducing the risk of armed forces influencing the democratic process," Ibisevic emphasizes.

After war (Infographic by RBC-Ukraine)

After war (Infographic by RBC-Ukraine)

If thousands of military personnel on active duty are allowed to participate in politics at the same time, a whole range of scenarios is possible. From a repeat of the 2014 experience with People's Deputies who were also military commanders to the more dangerous example of a number of African countries where the army and the government are almost inseparable.

However, Ukrainian law currently allows military personnel to combine service and politics. The only issue is adjusting the procedure for their candidacy.

"Here, of course, decisions must be made and possible conditions determined under which leave would be granted for campaigning, what the procedure should be, and whether leave is needed specifically for registration. Perhaps the transfer of the mechanics of submitting documents to electronic form—such a possibility is provided for in the code, it needs to be clarified there," Kornienko tells RBC-Ukraine.

***

In general, most of the technical problems associated with holding elections can be solved. The state of the political infrastructure and the readiness of the people raise many more questions, Dubovyk points out in a conversation with RBC-Ukraine.

This concerns not only the parties whose representatives are to work in precinct commissions, but also the ability of civil society organizations to perform their monitoring functions. A separate issue is the need for equal and clear conditions for pre-election campaigning.

In this sense, elections go far beyond the technical procedure of voting. No less important will be the restoration of trust in politics after the war, when society is exhausted, and parties and the public sector are weakened. And, of course, when the threat from Russia remains.

Therefore, rushing may prove more dangerous than pausing. Elections that are questionable in terms of legitimacy are exactly what Russia is counting on in its attempts to cast doubt on the democratic nature of the Ukrainian state.

After the end of hostilities, Ukraine will face a difficult choice: either spend time rebuilding its political infrastructure and hold elections without questions about their legitimacy, or undergo a procedure whose results will have to be constantly justified.

And it is this choice that will largely determine the stability of post-war Ukrainian democracy.

Quick Q&A

— What is the main condition for holding elections in Ukraine according to the position of the President and the CEC?

— The key condition is the complete end of hostilities. In addition to the security factor, the Central Election Commission emphasizes the need for a transition period of at least six months before the start of the election campaign.

— What are the two main problems that arise in the context of voting by millions of refugees and IDPs?

— Infrastructure: damage to polling stations (about 20–25% in frontline areas) and registration: the need to accurately determine the location of voters and ensure that they can vote.

— Is the possibility of holding elections through the Diia app being considered?

— Not at this time. Mykhailo Fedorov noted that work on such a tool is not being carried out due to the lack of a legislative framework. However, Diia can be used for voter self-registration or to find the nearest polling station through the electronic office.

— What is the main difficulty in the participation of military personnel in elections as candidates?

— The main dilemma is whether military personnel should be discharged from service to participate in politics (as was the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina to maintain the neutrality of the army), or whether the state should create a mechanism for special leave for campaigning, which would allow them to combine service and candidacy.

Sources: CEC, UN, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, CEC Deputy Chairman Serhii Dubovyk, First Deputy Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada Oleksandr Kornienko, expert at the Center for Political and Legal Reforms Andrii Mahera, and public figure from Bosnia and Herzegovina Samir Ibisevic.