Ivan Franko's hidden story: Bizarre truths your school teachers didn't touch

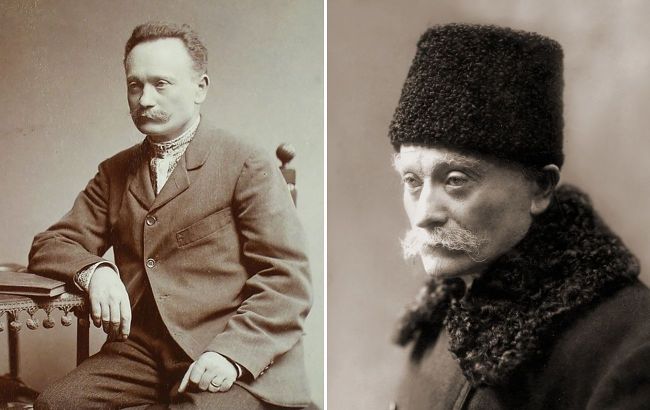

Little-known facts from the life of Ivan Franko (Collage by RBC-Ukraine)

Little-known facts from the life of Ivan Franko (Collage by RBC-Ukraine)

Ivan Franko is one of the greatest figures in Ukrainian culture, often perceived through the lens of school textbooks. But beyond the stereotypes lies a complex, contradictory, and deeply human personality. What little-known facts about Ivan Franko are not told in Ukrainian literature lessons?

Franko slept in coffins

While studying at the Drohobych gymnasium, Franko lived with relatives who were undertakers. Due to a lack of space, he had to sleep in the workshop among coffins, sometimes inside them. He later recalled this eerie experience with bitter irony.

Franko owned over 12,000 books

His personal library amazed even scholars: it contained around 12,000 volumes. Among them were rare philosophical treatises, Sanskrit dictionaries, and ancient Bible translations. Books were the foundation of his self-education and a source for his numerous translations.

He starved almost to death

After one of his arrests, Franko found himself in extreme poverty. He had no money for food and went three days without eating. A hotel worker happened to find him unconscious and saved his life.

Left an autograph on the Painted Stone

During a journey through the Carpathians, Franko left his signature on the Painted Stone near the village of Bukovets. This place was considered sacred even in pre-Christian times. Franko was fascinated by folk legends and believed that the land of the Hutsul region held special power.

Believed in the supernatural

Franko mentioned hearing voices suggesting new ideas for his works during illnesses in his letters. He also believed that the spirit of Adam Mickiewicz helped him find a lost drama by the Polish classic. His spiritual searches intersected with mysticism and occultism.

Used the "Drahomanivka" script

Franko actively supported the spelling reform created by Mykhailo Drahomanov. In 1878, he published several texts using this alternative orthography. It was closer to a phonetic principle but did not gain widespread acceptance.

Lviv residents bought him a house

At the beginning of the 20th century, Franko lived in great poverty and did not even have a home. Students and the establishment of Lviv raised funds and bought him a small house, a gesture of public gratitude and recognition.

House No. 152 on Franko Street in Lviv. Architect Martyn Zakhodny (1869–1910). Now, the Lviv National Literary-Memorial Museum of Ivan Franko. (Photo: Wikipedia)

House No. 152 on Franko Street in Lviv. Architect Martyn Zakhodny (1869–1910). Now, the Lviv National Literary-Memorial Museum of Ivan Franko. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Nominated for the Nobel Prize

After Franko's death, his candidacy for the Nobel Prize in Literature was submitted in 1916. Although the prize was not awarded posthumously, the nomination confirms his high regard for his work. Interestingly, the nomination was initiated by scholars from Austria-Hungary.

A cruise liner was named after him

In the 1960s–70s, a passenger liner named "Ivan Franko" operated in the USSR. Built in East Germany, it was the flagship of a series of cruise ships serving international routes. Franko's name became a symbol of cultural prestige.

His signature appeared on currency

A fragment of Franko's text printed in Drahomanivka appears on the 20-hryvnia banknote issued in 2003. This is a unique case of using reformed orthography on official state currency. The design references his linguistic and ideological struggles.

Front side of the 20-hryvnia banknote. 2003. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Wrote under 99 pseudonyms

Ivan Franko used nearly a hundred pseudonyms, including Dzhedzhalyk, Myron, Unknown, The Stonecutter, Nirvana, and The Living. This allowed him to publish in censored newspapers and separate the themes of his publications. Some of his pseudonyms remain a mystery to this day.

Could have become a priest

Franko's parents dreamed that their son would enter the clergy. He studied under a church cantor but chose to attend a gymnasium and pursue a secular path. This early experience shaped his later critical views of the church.

His wife suffered from mental illness

Olha Khoruzhynska, Franko's wife, suffered from serious mental health disorders. Her condition only worsened over time, affecting family life. Despite the difficulties, Franko remained a caring father to their four children.

Ivan Franko with his wife and children on the steps of their villa, September 1904. Children from left to right: Petro, Taras, Anna, Andrii (Photo: Wikipedia)

Had political ambitions

Franko ran twice for the Austrian parliament, hoping to defend the rights of Ukrainians. Both times, his candidacy was blocked due to pressure from church and state authorities. His political defeat was a great disappointment.

Listed as a "dangerous person"

Austro-Hungarian police considered Franko a particularly dangerous intellectual. He was repeatedly arrested, his letters intercepted, and his works removed from libraries. This indicates the powerful influence his ideas had on society.

Wrote detective stories

Franko was one of the first Ukrainian writers to explore the detective genre. His works "For the Home Hearth" and "Robbery" include investigation, intrigue, and psychological analysis elements. It was an attempt to align Ukrainian prose with European standards.

Worked in a coal mine

Franko worked in a mine to study labor conditions. He didn't just observe—he actively participated in the work, communicated with laborers, and lived among them. This experience inspired many of his socially themed writings.

Wrote plays for the theater right on the street

Franko often wrote in parks or on benches in downtown Lviv. People recalled how he would jot down lines for plays in his notebook with a pencil. This is how such famous works as "Stolen Happiness" and "The Dream of Prince Sviatoslav" came to be.

Suffered from polyarthritis but kept writing

In his later years, Franko had severe polyarthritis and couldn't hold a pen. He dictated his works to his son Andrii, continuing to create despite physical pain. It was a testament to his incredible strength of spirit.

Was buried by students, peasants, and workers

Although the authorities ignored Franko's funeral, ordinary people carried his coffin, a silent acknowledgment of his contributions to the nation. The Stonecutter's funeral became a national event without any official presence. He was buried at Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv.

Tombstone on the grave of Ivan Franko at Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv (Photo: Wikipedia)

Tombstone on the grave of Ivan Franko at Lychakiv Cemetery in Lviv (Photo: Wikipedia)

Sources: Bila Khata, BUKI, Wikipedia, official page of the Franko House.