How USSR used food as weapon of control — From cheap ice cream to stolen dishes

How the USSR controlled people with food (photo: Getty Images)

How the USSR controlled people with food (photo: Getty Images)

The well-known phrase from the times of the Roman Empire, "bread and circuses," is not accidental. The Roman Empire fed the population with bread and wine not only for humanitarian reasons but also to preserve peace and loyalty. After all, food can also be a powerful tool of influence. We studied how the USSR was using gastronomy as a tool of control and equality.

How the USSR influenced the cuisines of the countries it occupied

Gastronomic culture even has a distinct concept, "Soviet cuisine." However, according to Ukrainian gastronomic researcher Olena Braichenko, the USSR did not aim to deliberately create this concept. The sphere of food and nutrition has changed significantly over just 70 years.

"In apartments built after World War II, kitchens were tiny. The idea was that you shouldn't really be eating at home at all. But in the 1960s, the image of the woman who cooked everything and took care of the household appeared. There is a distinctly patriarchal undertone," says Olena Braichenko.

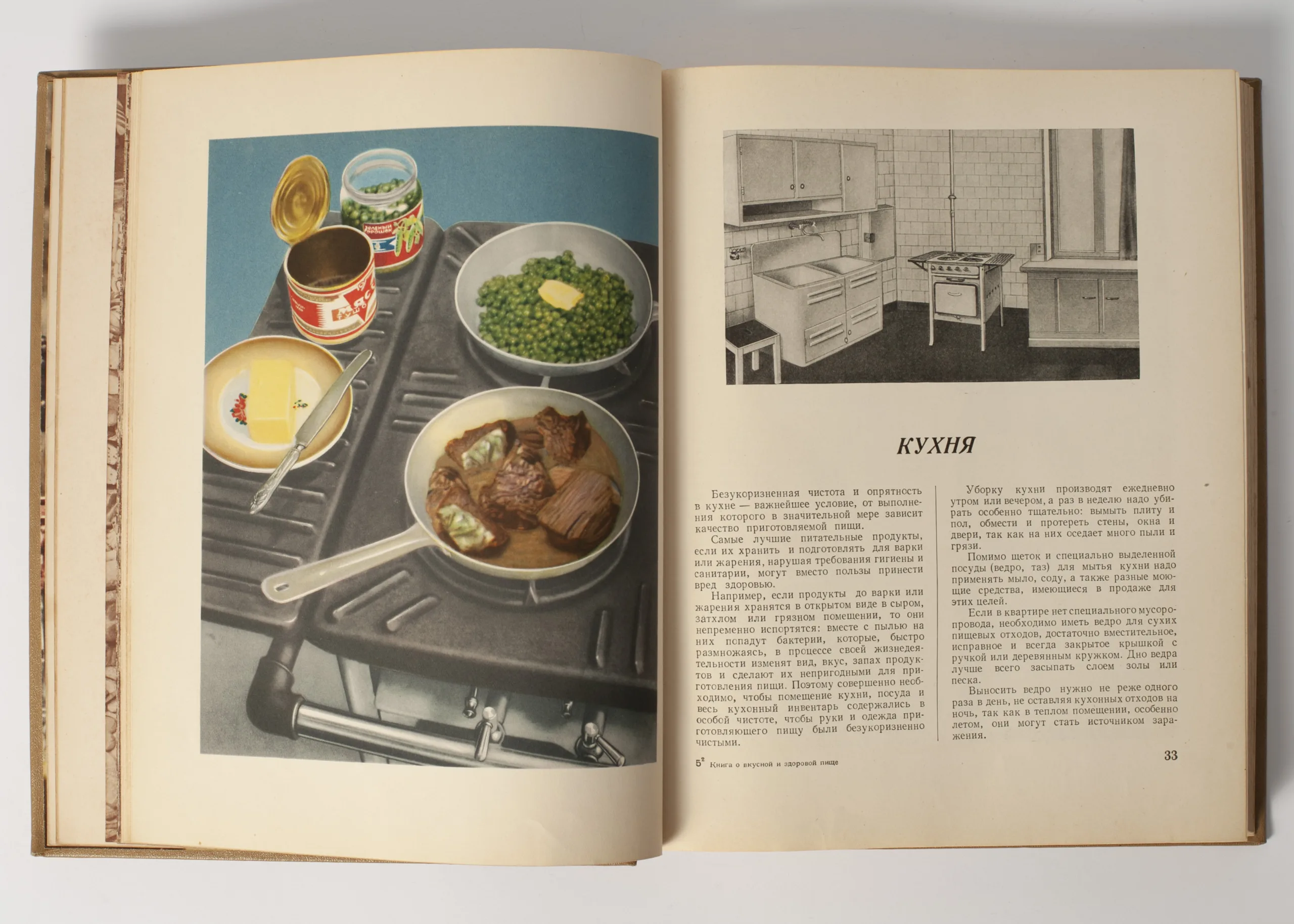

The beginning of this period was marked by the publication in 1939 of the first major cookbook on Soviet cuisine, "Book on Tasty and Healthy Food."

In fact, the idea of "Soviet cuisine" is a combination of national dishes from various countries absorbed by the Soviet Union. Moreover, even the very essence of the food industry did not originate with the "great minds" of the USSR.

In 1936, People's Commissar of the Food Industry Anastas Mikoyan visited the United States, where he stayed two months. There, he studied American practices in the food and mass catering industry.

Anastas Mikoyan in the USA (photo: Russian media)

Afterward, the USSR began building modern food industry enterprises, particularly for the production of dairy and meat products, canned fish, meat, vegetables, fruit, and condensed milk. Posters even appeared with hamburgers, but the rhetoric quickly shifted.

Incidentally, Mikoyan's personal tastes played a significant role in shaping consumer culture. For example, in 1936, he declared himself a great supporter of ice cream production.

He purchased equipment in the US for the full production and distribution cycle of ice cream, including street refrigerators. Mikoyan even personally selected the flavors. Soviet factory production of ice cream grew from 20,000 to more than 46,000 tons in just six years.

During his trip, Mikoyan was also impressed by the American tradition of drinking orange juice for breakfast. Since oranges did not grow in the USSR, they decided to produce a somewhat different juice, tomato juice.

Bright representatives of the Soviet menu include eggs with mayonnaise, well-known salads, solyanka, borscht, kharcho, okroshka, shashlik, pelmeni, and goulash. Many of these dishes belong to other national cuisines. For example, kharcho is Georgian, shashlik comes from the Caucasus, and pilaf from Eastern countries.

Dish names were often changed. For example, consommé printanier was renamed broth with herbs, boyar pochlebka became potato soup, and even the famous chicken Kyiv cutlets turned into chicken cutlets stuffed with butter.

Another curious phenomenon is "Soviet" or "Artemivske" champagne, since the drink can only be called champagne if it is produced in the historical Champagne province in France.

More is better than tastier

Some researchers believe that Russians, specifically in the USSR, valued the quantity of food much more than refinement.

In the Soviet Union, food was regarded merely as fuel for the body. The idea of food as a source of pleasure was absent.

"We must not give the consumer what he wants. We must give the consumer what he needs," wrote party official Abram Holtzman in his work on communist wages.

This is where the idea of "Eat what you're given" began to take root.

"In the Soviet Union, the idea that food should not be about pleasure was strongly promoted. It should be useful, and that was enough. Focusing on sensations in the body and thinking about variety did not align with the idea of control at all," says clinical psychologist Olena Shyrokova.

The main expression of this new food ideology during Stalin's era was the "Book on Tasty and Healthy Food." It was not just a collection of recipes but an encyclopedia for Soviet housewives, for whom it was primarily intended.

It is worth noting the title of the book. For the first time, food was expected to be tasty.

Book on Tasty and Healthy Food (photo: Russian media)

Book on Tasty and Healthy Food (photo: Russian media)

According to various researchers, the purpose of the cookbook was not to depict Soviet reality but rather to assert that "Soviet power will solve all modern problems."

For example, let's look at the section of the book "Dry breakfasts." It included products such as oatmeal, corn, wheat, and rice flakes, puffed rice, crushed bran, and crushed wheat cookies.

But only three of them were actually available at the time of publication. At the same time, people were urged to force themselves to eat black caviar.

Which dishes Russia stole from other nations

It is fair to call Russia the greatest thief in the world, from territories to recipes.

Pelmeni are often considered "originally Russian," but this is not true. The dish was actually stolen from the Komi and Udmurt peoples. The name comes from their words "pel" ear and "nyan" bread. The territories of these ethnic groups are part of modern Russia.

Herring under a fur coat is another story. Scandinavian and North German cookbooks contain recipes with the same set of ingredients. They were called "herring salads."

Potatoes, carrots, beets, and herring were quite available ingredients. But the story of the origin of the "fur coat" was not just embellished but completely rewritten.

There is a legend that in 1918, a cook sought to calm revolutionary rebels and presented a salad where each ingredient symbolized something.

Thus, the vegetables in the "fur coat" represented peasants, beets represented the Red Army, herring was the proletariat, and mayonnaise was the bourgeoisie, so as not to forget about the enemies. Soviet historians also claimed that the word "shuba" (fur coat) was actually an acronym for the phrase "Chauvinism and Decline, Boycott and Anathema."

Soups and broths are widespread in Russian cuisine. On July 1, 2022, Ukrainian borscht was inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Many countries may consider borscht their national dish. However, only in Ukraine did a certain borscht tradition develop over centuries. Yevhen Klopotenko collected evidence that recipes were passed down for at least three generations in a single family.

Food is not only about physical need. It is about politics, culture, identity, and memory. The way we eat and what we eat was shaped not only in families but also under the pressure of empires, systems, and ideologies.

And only by realizing this can we reclaim our freedom, even in such a simple act as choosing what to put on our plate.

Sources: exclusive comments from gastronomic researcher Olena Braichenko, clinical psychologist Olena Shyrokova, lecture by historian and researcher Olena Styazhkina, Book on Tasty and Healthy Food.