Mark Ellis, International Bar Association: 'Putin won’t appear in The Hague in short term'

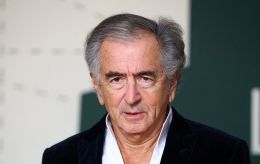

Mark Ellis, executive director of the International Bar Association (Photo: RBC-Ukraine, Vitalii Nosach)

Mark Ellis, executive director of the International Bar Association (Photo: RBC-Ukraine, Vitalii Nosach)

Why the special tribunal for Russian aggression has yet to start, why some countries oppose ignoring the immunity of Russia's "trio," and whether Putin will receive an ICC arrest warrant for war crimes – Mark Ellis, executive director of the International Bar Association and an expert in international law, said in an interview with RBC-Ukraine.

The Special Tribunal for Russian aggression has yet to begin its work, even though nearly three years have passed since efforts to establish it began. Moreover, Ukrainian and Western experts suggest it will not launch in 2025, though some progress is expected.

Mark Ellis, Executive Director of the International Bar Association and an expert in international law, previously worked as an advisor during the tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda and initiated the eyeWitness application. He now regularly visits Ukraine and helps investigate Russia's war crimes.

Why some countries oppose prosecuting Russia and specifically Vladimir Putin, why the Russian dictator has still not received an arrest warrant from the ICC for war crimes, what consequences Mongolia may face for not arresting Putin, and what dangerous trends can be observed in countries' attitudes toward international law – Mark Ellis spoke about this in an interview with RBC-Ukraine.

— My first question concerns the tribunal. Some believe that the tribunal against Russian aggression will not start working in 2025. Why does it take so long to organize a court against the aggressor who invaded so openly?

— There are two primary reasons why this process is taking time. First, it is essential to recognize the significant support already in place. For instance, the formation of a core group and backing from the Council of Europe are meaningful steps forward. However, establishing a special tribunal to prosecute an individual like Vladimir Putin for the crime of aggression—a charge aimed at individuals, not states—is a monumental task for the international community. While I strongly support this effort, it’s important to note the challenges involved.

The second reason is the unprecedented nature of this situation. This would be the first time a tribunal focuses on a country with nuclear weapons and one of Russia’s size and influence. Political will is a critical factor, and Russia’s position creates challenges on this front. While I firmly believe the crime of aggression is an international crime that demands accountability, not all countries are equally motivated to act.

For example, some nations in the Global South may view Russia’s war against Ukraine as a European issue rather than a global one. They might also perceive hypocrisy, questioning why Russia is being singled out when they believe leaders from other nations, including the United States, have committed similar acts. Additionally, economic considerations in opposing Russia weigh heavily on these countries, further complicating the political landscape.

Then, there are legal complexities that significantly impact the tribunal’s establishment. One key issue is head-of-state immunity. Should the special tribunal recognize such immunity, or should it disregard it? Personally, I believe head-of-state immunity should not be recognized. However, opinions within even the G7 are divided. Some worry that ignoring head-of-state immunity could set a precedent that might later target their own leaders. This is one of the most contentious legal issues facing the tribunal.

— That was my second question.

— Yes, this issue of impunity is highly contentious. If a special tribunal recognizes head-of-state immunity, figures like Vladimir Putin and others in his circle would remain untouchable while holding office ( however, they would lose that protection after they left office). On the other hand, insisting on a tribunal that does not recognize such immunity could lead to resistance from some countries. For instance, the United States and several other key countries might refuse to participate in such efforts.

Again, creating an international tribunal that overcomes the hurdle of head-of-state immunity is a significant challenge. It can be achieved, especially with strong support from the Council of Europe and participation from other countries. However, I personally believe that a tribunal that recognizes head-of-state immunity could undermine its very purpose. We know who is most responsible for this crime of aggression; it’s Vladimir Putin who must be brought to justice.

– I don't understand the part about precedent. We had several precedents before. Not with nuclear countries, but anyway. For example, we had the tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and when there was the Rwandan genocide against Tutsi. We had tribunals before and saw ICC actions for that. As for Russia, I understand its influence on the political area, but it is a military criminal.

– You’re right to draw those parallels. Leaders like Milošević, Karadžić, Charles Taylor, and Al-Bashir have faced or will face justice. However, the UN Security Council created the tribunals for Yugoslavia and Rwanda under its Chapter VII powers.

The Special Court for Sierra Leone focused on Charles Taylor and was created at the request of the Security Council to the Secretary-General to negotiate a treaty agreement with Sierra Leone. A special court for the crime of aggression against Russia cannot rely on the Security Council because Russia is a permanent member and would veto any such move. Thus, we need to create a new modality.

– But that’s ridiculous. I mean, Russia's membership in the Security Council, given its invasion of another state.

– I agree. However, the UN Charter provides for five permanent members of the Security Council, and each member has veto authority. An alternative modality would be for the UN General Assembly resolution supporting the creation of a tribunal. This happened with the creation of a special war crimes tribunal in Cambodia ( the ECCC) through a General Assembly resolution. It was a hybrid tribunal but also had international recognition and credibility. However, there does not seem to currently exist the political will within the Assembly to do the same for Ukraine.

The point is that tribunals need to be seen as “international.” This is crucial because “international” tribunals, like the ICC, do not recognize head-of-state immunity. Without such status, international law requires states to uphold head-of-state immunity. This means that Ukraine could not prosecute a sitting head of state on its own.

These legal and political inconsistencies create substantial hurdles for the proposed tribunal targeting Russian leaders. However, the ultimate determinant is political will. The international community must continue to push for accountability and justice.

– But for us, it is a crucial point to see Putin in jail. Or at least to take him to court.

– It’s important to distinguish between legal actions against someone like Putin and the process of apprehending him. The ICC’s arrest warrant for Putin is a significant step in international law. It sends a strong message about accountability, focusing on the law rather than the individual’s status. This is worth celebrating.

However, apprehending Putin is another matter entirely — one that hinges on political will. Putin won’t appear in The Hague in the short or even medium term. But history shows that seemingly untouchable leaders eventually face justice. Milošević, Karadžić, Charles Taylor, Saddam Hussein, and even Eichmann (Adolf Eichmann was a Nazi figure known as the "architect of the Holocaust") were eventually held accountable.

Crimes like the ones committed by Putin have no statute of limitations. Sometimes, justice takes time, which can be frustrating, but persistence is key. Countries must continue to emphasize the importance of international justice. This ensures that such crimes do not go unpunished.

– Actually, my third question was about warrants. I’d like to get a little deeper into this question. In your opinion, why did the ICC issue arrest warrants against Putin and Lvova-Belova? Those warrants were about illegal children's deportation. But we had another case with Netanyahu being issued a warrant for military crimes, but not Putin. Why?

– I believe there are two main reasons for this. First, the charge of illegal deportation of children is particularly powerful. The horror of taking thousands of children and attempting to “Russify” them resonates universally. Even those who might disagree with charging Putin for the crime of aggression find this charge unacceptable. It resonates strongly even in the Global South.

Second, Putin and Lvova-Belova made no effort to hide their actions. Moscow openly acknowledged the deportation of Ukrainian children as state policy. The ICC Prosecutor didn’t need to dig deep to build this case because it was already laid bare. That clarity made it an obvious first step.

There is also a historical dimension. Putin’s actions mirror the policies of Nazi Germany during World War II. For example, Himmler advocated kidnapping children to “Germanize” them. This historical parallel adds weight to the decision to pursue this charge first. However, I’m confident this will not be the last charge against Putin. There is overwhelming evidence that Putin has committed other crimes, both directly and through the concept of command responsibility.

– Thank you. It's difficult to understand the motives when we experience such tragedies as the strike at the children's hospital in Kyiv. Karim Khan visited the site and spoke to doctors there. He saw everything with his own eyes. Even the parts of the Russian missile. After that, he just requested warrants for Netanyahu but not for Putin. I want to believe that there will be another warrant.

– Additional charges are inevitable. The ICC has already issued arrest warrants for senior Russian military leaders, showing the prosecutor is building cases methodically. I’m convinced more charges against Putin are forthcoming.

– In your opinion, what responsibility should Mongolia bear for refusing to arrest Putin during his visit?

– Mongolia is a State Party to the Rome Statute, obliging it to arrest any individual indicted by the ICC. However, Mongolia allowed Putin to visit, claiming head of state immunity. The ICC rejected this argument, but Mongolia proceeded regardless, likely due to its reliance on Russian energy, But that’s no excuse. If exceptions are carved out, every State Party could do the same. However, Mongolia’s actions have drawn significant negative attention, including from the International Bar Association, which hopefully serves as a deterrent to other countries.

– And could Mongolia be out of the Rome Statute?

– No, State Parties cannot be forcefully removed. Unless Mongolia repeatedly violates its obligations, the Assembly of State Parties has limited options. They cannot impose economic sanctions. For now, diplomatic isolation may be the most effective way to send a strong message.

– Some countries have already claimed that they may meet with Netanyahu. What do you think about this tendency? Do you see that maybe the ICC or all international law system will lose their authority?

– If State Parties decide to disregard their obligations to arrest individuals indicted by the ICC, it would weaken the court’s authority. There have been past incidences of state refusals, such as with South Africa, however, regarding Putin, Mongolia’s actions appear to be an isolated incident. We’ll see how countries respond, especially under political pressure. For instance, the United States, which is not a State Party, is about to impose sanctions on the ICC, which could erode the court’s authority. The situation remains fluid, and the next few years will be critical in determining the ICC’s standing and effectiveness.

– You’ve addressed whether Putin might go to jail. Do you see any other tools to punish him?

– The ICC’s arrest warrant alone has significant consequences. Putin is a prisoner within his own country. With the exception several “outlier” countries, Putin’s travel is restricted. Countries are also collecting evidence of his crimes under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Economic sanctions against Russia add further pressure. While the process may be slow, it is effective. Putin’s actions have isolated Russia, and this will have lasting repercussions.

– I'm afraid that he will die before this process will end.

– If he does, history will remember him as an indicted war criminal. Putin sees himself as a grand leader, but his legacy will be that of a dictator and a war criminal. Domestic politics in Russia will also shift over time. While the pendulum currently favors Putin, history shows this won’t last. Russia’s position in the international community has already been severely diminished.

– Yes, history has shown us similar examples before. For example, Stalin. When the Russians idolized him, they just threw him out.

– Exactly. That’s how history unfolds.

– As for our war, do you see the features of genocide in Russian aggression in their actions?

– This is a debated issue, but I believe there is evidence of genocide. Genocide requires specific intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, religious, or racial group. Russia’s actions — including mass deportations and the Russification of Ukrainian children — demonstrate this intent and genocidal acts. Putin and other officials have openly stated they do not recognize Ukraine as a country or Ukrainians as a people, further supporting this argument.

While proving genocide is challenging due to the specific intent requirement, I believe the evidence is there. Ukraine’s nationality recognized internationally, and ethnicity, including language, culture, traditions, and shared sense of community, qualify it as a protected group under the Genocide Convention. The ICC may be taking time to ensure they have a strong case, but I believe the court could eventually pursue these charges.

– Maybe some experts or the ICC don't see features of genocide because they are afraid of some precedent.

– It’s possible. Ideally, decisions should be made based on legal grounds rather than political considerations, but that’s not always the case. Genocide charges require incontrovertible evidence, which takes time to gather. However, I believe that, in time, the legal process will fully reflect the scope of Russia’s actions.