'I fought for a passport': What life looks like inside Ukraine's Russian POW camp

Russian prisoners of war (All photos: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

Russian prisoners of war (All photos: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

How Russian prisoners of war are treated in Ukraine and what they say about the war and their role in it - read in the report by RBC-Ukraine from a camp for Russian prisoners.

In its war with Russia, Ukraine strictly adheres to all international standards and agreements. Russian prisoners of war are held in full compliance with the Geneva Conventions — they receive medical care, work, and have their own rights and duties.

Moreover, the facilities where POWs await military swaps are open not only to diplomats and humanitarian organizations but also to the media. One of the camps even hosts regular open days — journalists can see the conditions the prisoners live in and talk to them directly.

Reception area and infirmary

One of the colonies for Russian POWs is located in a small village in western Ukraine. The tall stone wall topped with barbed wire can be seen from the road as we approach. We ask the driver to stop near the main gate. The visit starts in the morning and is scheduled to last until around 3 p.m.

Inside, we enter an iron maze of narrow corridors and bars, where guards meet us and lead us deeper into an administrative building, into a tidy assembly hall. After a short while, a representative of the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Petro Yatsenko, appears before the journalists.

"We'll be here until three. Please stay together as a group. You can stay behind later to interview prisoners if they agree. Just make sure you leave before evening — otherwise, the colony staff might mistake you for inmates and lock you up for the night," Petro jokes, lightening the mood.

After a quick briefing, we are taken to a small courtyard. On the wall by the entrance, there's the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and beneath it — a small plaster angel. While we gather, the guards point to a patch of ground where flowers are planted in the shape of Ukraine’s coat of arms. The first thing we see upon entering the camp is a church.

"It’s a Greek Catholic church, but Russians can pray here too — the rites are similar," says the Coordination HQ representative.

Inside, there's no scent of incense, though the worn Bibles and burned-down candles show that prisoners visit it regularly. Psalters and New Testaments appear again and again in the living quarters — on about every fifth bedside table.

We follow the same route that new prisoners take upon arrival. The first stop is the intake area. Here, soldiers are examined by doctors, issued uniforms, shoes, and hygiene supplies, and taken to the showers. The air is thick with the smell of dirty clothes — the room is filled floor-to-ceiling with bags of their belongings.

"Each bag has a tag with a name on it. When they're exchanged, they get their belongings back. They're allowed to keep jewelry, chains, wedding rings — even one had an earring. We don't confiscate anything, as required by the Geneva Conventions," Yatsenko explains.

Nearby are dozens of boxes — gifts from the Red Cross — filled with toothbrushes, toothpaste, soap, toilet paper, and shaving kits.

The showers, despite the heavy smell of chlorine, feel much more pleasant than the storage room. Two years ago, the stalls were open; now each has its own curtain.

"Everything here is for their comfort. Even these showerheads — they're pretty expensive. I'm sure most Russians back home have never seen anything like them," Yatsenko adds.

New arrivals spend two weeks in quarantine, isolated from the others — they don't work or live in the common block. Once doctors confirm they're healthy, they join the rest. As we walk past rows of identical gray buildings, prisoners watch us from the windows. For many, such media visits are a rare break from routine.

Next, we reach the camp store — a small room with a counter and shelves lined with food and toiletries: canned goods, candy, cookies, instant noodles, soap, and oddly — Easter cakes, stacked across the bottom shelf.

Prisoners earn around 300 hryvnias (around 7 USD) per month, as the conventions stipulate. They also have accounts where relatives can transfer money. They don't have cash on hand — purchases are recorded in a ledger and deducted. They can also order items through the Red Cross.

"The Red Cross visits regularly, and prisoners can request what they want. Next time, it's delivered," explains Yatsenko.

"Is there a limit? Can they ask for jamón?" someone jokes.

"There are categories, of course. No one's bringing jamón here. But they can order basic things — meat, canned food, sweets, cookies."

Before entering the infirmary, we step onto a wide yard and finally see the POWs themselves. They stand along the wall, quietly observing us. We watch them back — openly. Then we decide to approach.

.jpg)

One soldier sits on a bench, stretching out a bandaged leg. He has Central Asian features and, oddly, greets us with a smile. His name is Talibjun, from Tajikistan. He just turned 31 — a birthday he celebrated right here in the camp.

“How did you end up in the war?”

“I signed a contract myself.”

“Why?”

“I live in Russia… I have a house there. I needed a passport, so I went.”

“You went to war just to get citizenship?”

“Well, yes.”

Talibjun keeps smiling, even when he doesn't know how to answer questions — for example, why Russia invaded Ukraine. He shrugs it off as "politics." As it turns out, that's a typical response among Russian POWs. They don't want to think — or talk — about why they ended up in this war, and then in captivity.

Prisoner of war Talibjun (photo: Vitalii Nosach/RBC-Ukraine)

Ukrainians who fought for Russia, by contrast, tend to be more aggressive. They insist they're fighting for their motherland — usually referring to occupied Donetsk, which they call a republic.

One of them introduces himself as Sergey, but refuses to speak on camera. He bristles when we call Donetsk "occupied." When he runs out of arguments, he mutters, "You should be occupied too," pulls a medical mask over his face, and walks away.

Talibjun, on the other hand, keeps calling journalists over. He says he keeps applying for an exchange, but somehow, he's never included. He's convinced it's Ukraine's fault — that Kyiv allegedly wants several Ukrainian soldiers in exchange for him. When we suggest that perhaps Russia simply doesn't want him back, he freezes for a moment — his smile fades for the first time.

"Doesn't it bother you that you had to go to war to get citizenship — and for unclear reasons at that?"

"If I want to live in a country, the most honorable way is to earn citizenship this way."

"Do you really think that's honorable?"

"That's my decision. Personal. So no one can reproach me later."

Then two young men sit down on the bench. One of them is 19-year-old Aleksandr from the Khabarovsk region. When we ask how far his home is from here, he says, "Nine thousand kilometers," then turns away, refusing to appear on camera.

The infirmary resembles a regional hospital after undergoing high-quality renovation. The walls and floors are covered with cream-colored tiles, and the rooms are equipped with expensive medical equipment — an X-ray machine, ultrasound, and diagnostic devices. Yatsenko explains that the Red Cross purchased the equipment, while Ukraine itself funded the renovation. Near the exit, there's a box nailed to the wall labeled "Complaints and suggestions." Inside, it's empty.

Residential block

Before lunch, we are taken to the residential buildings where the prisoners sleep and rest after work. The rooms are spacious and bright, with bunk beds and small bedside tables. Nearly everyone has books on it. Judging by their reading choices, many prisoners of war are either believers or trying to become ones — there are Bibles on the shelves and icons standing nearby.

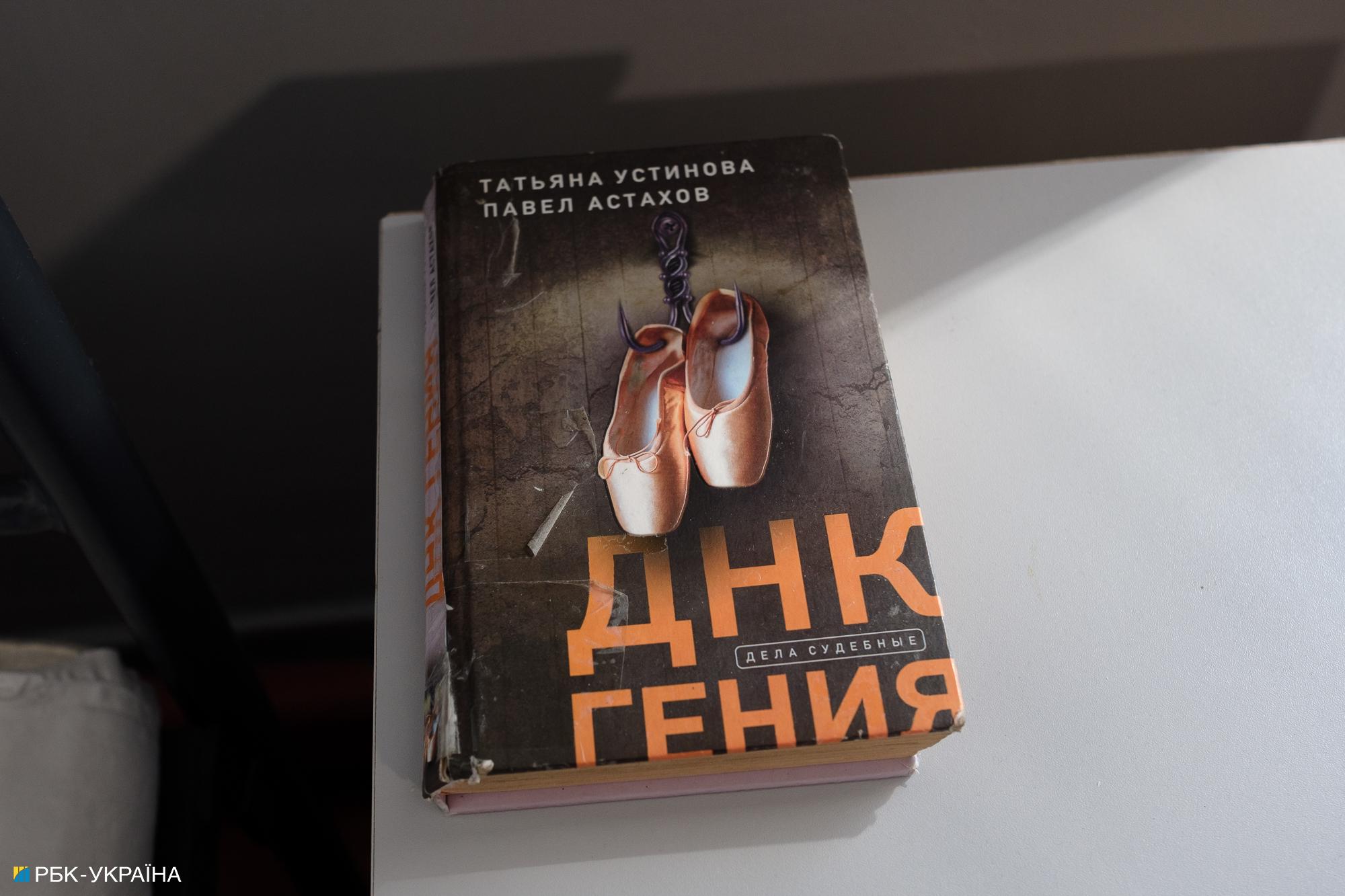

Some read history books like 'When Chersonesus Fell' or 'Vasiliy III.' Others seem interested in self-development — reading 'The DNA of a Genius' or 'From Time to Eternity: The Afterlife of the Soul.' Most books are in Russian, but there are also some in Ukrainian — probably read by Ukrainians who lived under occupation and were later sent to fight by Russia.

Camp staff say that over the years, many Russian prisoners have started to pick up Ukrainian themselves. After some time, they not only understand it but can even speak it. Their words are later confirmed by Maksim from Yekaterinburg, who says, "Of course, I understand you," almost without an accent.

After the sleeping quarters, we are shown the common room where prisoners watch TV, and then a small area with tables and refrigerators. Here they can play chess, write notes, or eat food they buy at the camp store.

The refrigerators are stocked with soda, sausages, canned food, mayonnaise, and containers with ready meals. Each prisoner also has their own box. On one shelf lies a notebook with a crookedly written label: "For me."

Canteen

On the way to what's called the Hetman Alley, we pass a small vegetable garden where zucchini grow. The prisoners are taught to cultivate the land themselves. Behind the garden are six greenhouses filled with tomatoes, peppers, and herbs. Everyone is surprised by the basil — a large purple patch growing between tomato bushes and dill.

Hetman Alley is the name of a stone corridor near the canteen. Portraits of Ukrainian hetmans hang on the walls alongside maps and national symbols — the viburnum, the trident, and the flag, like in a school classroom. The smell of food drifts out of the canteen — that familiar scent found in every cafeteria.

The prisoners pass through the gate, hands clasped behind their backs, and line up in rows of three. They do not look at the portraits or the map of Ukraine.

Inside the canteen, the noise mostly comes from the journalists — the prisoners speak quietly. The food is prepared by the POWs themselves, who work in the kitchen. Today's menu includes borscht (which looks more like cabbage soup), wheat porridge with a piece of beef, and a salad made from vegetables grown in the camp's greenhouses. Each person is given four thick slices of bread. The prisoners bake it themselves and offer us to try it. The bread is warm, fresh, and crusty — served with linseed oil and salt before everyone is called to the table.

The borscht tastes nothing like the traditional Ukrainian one — it's bland but rich. The meat is tender, and there's butter in the porridge. Some prisoners crumble bread into their borscht, turning it into an unappetizing mash. They eat quickly, eyes down. For a moment, the dining hall falls silent, broken only by the clatter of spoons against metal plates.

When they finish, the prisoners stand and say in unison, "Thank you for the meal." The tables are wiped down, plates removed, and the next group sits. Lunch happens in four shifts, followed by work.

Workshop

Next, we're taken to a workshop where prisoners make furniture — today, they're weaving garden swings and chairs. When we enter, many briefly look up from their work but, under the supervision of camp staff, quickly return to it.

We approach one of the men — he's wrapping the metal frame of a swing with brown rattan. When asked if we can film him, he agrees and introduces himself: Sergey Dmitriyev.

Sergey is 37. He lived in Russia's Yaroslavl region and has been to prison twice — first for robbery, then for murder. He grows awkward when speaking about his second sentence, though his unease doesn't come from remorse. What troubles him is something else.

"I had a chance to clear my record — and I did. But I didn't take that chance seriously. I messed up again, killed a guy, beat him up — he died. To avoid serving time, to clear my record again, I went for a second term."

Sergey also can't answer why Russia attacked Ukraine. He calls it "politics," and when we point out that because of this "politics," he's spending years of his life in war and captivity, he nods repeatedly. "Yeah, I agree with that." He then tries to reconstruct the sequence of events, describing the invasion as an intervention. Into what, exactly — he doesn't say.

Another prisoner introduces himself as Maks — not Maksim, just Maks. He's also 37, from Yekaterinburg, and says he went to war out of revenge. Maks spends a long time trying to explain his reasoning. He says Russia gives everything to its citizens, while Ukraine doesn't, even though it's a rich country. How that connects to his decision to fight, he doesn't clarify. Nor can he explain why his country had to attack ours.

"Of course it's bad, of course it's wrong, of course we're brotherly peoples — that's how it should be. Why it happened — 95, maybe 98 percent of people at war don't even know themselves. Me included. It's hard for me to answer that question. Well, it happened the way it happened."

The microphone near Maks’s face makes him uncomfortable — he keeps pointing at it and asking us to move it away. Then he freezes for a moment over the metal frame of a chair, realizing that while he was talking, he wrapped the rattan around the leg the wrong way. As we speak, an older man in glasses keeps trying to interrupt. When we finally point the camera at him, he smiles shyly, revealing a few lower teeth.

The older man turns out to be 52-year-old Vitaliy, born in Horlivka.

"I want to go home!"

"Then why didn't you stay home?"

"I'm a mobik! They took me right off the street."

Vitaliy struggles not to swear, but it's hard for him — he mouths curse words silently after almost every reply.

"You say you're for the DNR — why?"

"That's where I was born, grew up."

"But you were born in Donetsk."

"Well, yeah."

"Then why say DNR?"

"They renamed it — Donetsk People’s Republic or something like that."

Vitaliy doesn't really understand why he's here. During the conversation, he agrees with everything and then contradicts himself. When asked what happened and why Russia attacked Ukraine, he pats his chest and says he has his own opinion but doesn't want to voice it.

When we leave, the prisoners return to their work — though many keep glancing at us: some curious, others grim and detached.

***

How Ukrainian authorities treat prisoners of war can't help but stir mixed feelings among Ukrainians themselves — especially given the state in which Ukrainian soldiers come home from Russian captivity. For the entire civilized world, it's clear that Russia ignores the Geneva Conventions and basic human decency toward POWs.

And this is where the fundamental difference between Ukraine and Russia lies. While Moscow keeps proving to the world that dialogue with it is pointless, Kyiv continues to demonstrate that Ukraine is a civilized nation — an integral part of Europe — and one that deserves the world's support in defeating the Russian aggressor.