Human shield. Can European peacekeepers ensure security in Ukraine?

Photo: French soldiers (Getty Images)

Photo: French soldiers (Getty Images)

European leaders are actively discussing the deployment of their military contingent in Ukraine. What could it look like, will UN peacekeepers appear in Ukraine, and can they become a real security guarantee?

Contents

- France and UK as process leaders

- Prospects for expansion and US factor

- How peacekeeping missions work

- What makes missions effective and why they may fail

- Will the contingent guarantee the security

Negotiations on ending Russia’s war against Ukraine, diplomatic pressure from US President Donald Trump on Ukraine and Europe, as well as his attempts to reach agreements with Russia, have defined recent months. At the same time, the US President is not particularly taking into account the interests of Ukraine and Europe, aiming primarily to end the war as quickly as possible. In response, Europe is looking for ways to prevent such a scenario while maintaining constructive relations with the US. At the core of Europe’s vision is a plan to deploy its armed contingent in Ukraine.

The main drivers of the idea are French President Emmanuel Macron and UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer. According to the Wall Street Journal, both politicians presented their ideas to US President Donald Trump during their visits to the United States. On March 2, following an informal summit of European leaders in London, Starmer openly stated that Europe is ready to increase its support for Ukraine with "planes in the air and boots on the ground" in the event of a peace agreement with Russia.

"We will deploy a contingent to Ukraine to safeguard the implementation of this agreement," the British Prime Minister said.

Meanwhile, Macron will gather the chiefs of staff of countries willing to guarantee future peace in Ukraine in Paris this week.

At the same time, Polish President Andrzej Duda, on March 6, did not rule out a full-fledged UN peacekeeping mission. "Perhaps we will need certain peacekeeping monitoring forces, but I do not exclude the possibility that both sides will agree to UN forces," he said.

Ukraine has also put forward its proposals in this context. On February 27, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha stated that a ground component alone would not be sufficient. "Ensuring the security of Ukraine’s sky and sea is just as important, if not more so. Land, air, and sea must all be in focus," Sybiha emphasized.

As these statements show, there is no unified concept yet - even at the conceptual level. European politicians refer to "peacekeepers," "contingent," or simply "missions" with vague mandates. RBC-Ukraine has analyzed the concepts being considered, the types of missions possible under international practice and Ukrainian realities, and, ultimately, what this could mean for Ukraine.

France and UK as process leaders

The President of France Macron began voicing the idea of deploying troops to Ukraine a year ago, in February 2024.

"The French even offered to send their military brigade here to assist us. But at that time, Ukraine neither agreed nor refused," said Oleksandr Sayenko, the commander of the 67th Brigade in 2022-2023 and now a military analyst at the Independent Anti-Corruption Commission (NAKO), in a comment to RBC-Ukraine.

At that time, the idea remained at the level of hypothetical scenarios rather than an official proposal. Moreover, Macron's initiative faced significant resistance within France. The lack of a clear response from Ukraine even somewhat irritated the French President.

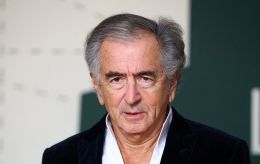

Emmanuel Macron and Keir Starmer at a meeting in London on March 3 (Photo: Getty Images)

A new impetus for the idea emerged in December, following Donald Trump's victory in the US elections. By late January of this year, the Financial Times reported that unnamed Ukrainian officials, in negotiations with their European counterparts, considered the deployment of 40,000–50,000 foreign troops as a security force along the front line a realistic possibility. At the time, this was discussed as part of a potential peace agreement with Russia.

Currently, the United Kingdom and France are the only countries that have publicly committed to deploying troops in Ukraine. However, their approaches differ.

Sources in the British government told Reuters that Keir Starmer insists on developing a peace plan that would include the deployment of British troops as part of a coalition of the willing. These sources emphasized that London wants to act jointly with allies but is prepared to take the lead if necessary.

According to BBC, the UK is considering scenarios in which British troops could act as peacekeepers along the front line. Meanwhile, sources in the British Ministry of Defense told The Guardian that the troop deployment plan is viewed as a strategic signal to Russia, but concrete details remain unsettled due to uncertainty over Washington's stance.

Regarding France, sources in the country's Foreign Ministry told Reuters that Paris is considering sending peacekeepers to monitor a ceasefire but only if Russia does not reject the proposal in negotiations. France wants to avoid direct conflict with Moscow and is seeking broader European support. Politico Europe sources in the French government say that negotiations are underway to involve Northern European countries, particularly Denmark and Norway, in the coalition of the willing. Additionally, sources in the French government told Le Figaro that Paris is ready to lead the coalition alongside London but is also waiting for a clear position from the United States.

Prospects for expansion and US factor

Europeans are considering the possibility of deploying a military presence in Ukraine under two conditions, said Rafael Loss, a policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, in a comment to RBC-Ukraine.

First, if the US administration agrees to a backstop, meaning that European forces would receive American security guarantees and potentially indirect support from the US.

Second, there would need to be a ceasefire that ends the current phase of hostilities, meaning that Russia would have to halt its aggression.

"Both of these look increasingly unlikely, and so Europeans will have to reconsider their options. But intense talks are continuing in different formats among European civilian and military leaders," Loss said.

During a meeting with Macron on February 24, Trump stated that he saw "no problems" with the idea of peacekeepers.

"Peacekeeping missions would be better than all these deaths," he said.

However, overall, the Trump administration remains skeptical of the idea, viewing it as "Europe's problem." A Pentagon representative, speaking anonymously to CNN, stated that US military forces would not participate in ground operations but that the US could provide technical support to European forces.

Emmanuel Macron and Donald Trump during a meeting in Washington on February 24 (Photo: Getty Images)

The US is also taking Russia's position into account. Two US officials involved in preparing meetings with the Kremlin reported that the deployment of foreign troops in Ukraine was discussed as one of the security guarantee options, but Russia rejects any NATO presence.

On March 6, the Foreign Minister of Russia Sergey Lavrov openly declared that Moscow was categorically against the deployment of a European peacekeeping contingent in Ukraine. According to him, deploying peacekeepers would be a "direct, official, and overt involvement of NATO countries in a war against Russia."

During recent visits to Washington, both Macron and Starmer attempted to persuade Trump of the benefits of such a scenario for the US after the war ends. So far, these efforts have yielded limited results. However, Trump's stance may shift once again following the signing of a minerals agreement with Ukraine, expected this week. Meanwhile, Macron and Starmer are rallying potential mission participants.

"In addition to France and the UK, Germany, as Europe’s biggest country, would also be expected to contribute meaningfully to the European military presence in Ukraine. In addition, the Nordic countries have been involved in relevant discussions and would likely contribute troops, as would the Netherlands. Ukraine has been keen to have Turkey join the coalition – so it will be interesting how they fit in with the European setup," Loss told.

According to him, Canada and Australia should also not be overlooked, but "these discussions are at a very early stage."

The mission composition is undoubtedly important, but the key question is how effective it can be and what practical benefits it can offer Ukraine. In this regard, it is necessary to examine past experiences with peacekeeping missions.

How peacekeeping missions work

Even if France, Britain, and other willing participants develop a clear concept for their mission, they cannot simply deploy troops to another country. Legal procedures must be followed, which vary depending on who is conducting the mission.

Several organizations around the world carry out peacekeeping missions aimed at maintaining peace, stability, and conflict resolution. The foremost among them is the United Nations (UN). Its peacekeepers, known as the "Blue Helmets," operate under the mandate of the UN Security Council. As of the beginning of this year, there are dozens of active UN missions involving more than 70,000 peacekeepers.

NATO also conducts missions, often in collaboration with the UN or under its mandate. Examples include the ISAF mission in Afghanistan and the KFOR mission in Kosovo. These missions are usually military and focus on ensuring security in conflict zones.

UN peacekeeper in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: Getty Images)

UN peacekeeper in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: Getty Images)

The European Union carries out peacekeeping and stabilization missions under its Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP), such as EUFOR Althea in Bosnia and Herzegovina and EUNAVFOR for combating piracy off the coast of Somalia. Other regional organizations also conduct peacekeeping missions within their areas of influence - for example, the African Union in Somalia and Darfur, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

A resolution from the Security Council is required for UN peacekeeping missions. Since Russia and China, along with Ukraine’s partners - the United Kingdom and France - hold veto power, such a mission is practically impossible for political reasons, not to mention logistical, financial, and personnel challenges.

Notably, Paris and London can block mission models undesirable for Ukraine, such as those promoted by Russia, potentially involving Kremlin-aligned satellite states. According to Bloomberg, this issue is already being discussed as a possible condition for a ceasefire.

NATO, the EU, and other regional organizations usually conduct missions with the approval of the UN Security Council. However, this approval is not always mandatory - it is often enough just to notify the UN. Still, both the EU and NATO are complex organizations that require full consensus among member states. This means that opposition from Hungary or Slovakia, for instance, could completely block a decision.

Another option is multinational forces - coalitions of states that come together to respond to a specific crisis. Their deployment only requires the consent of the country where they will operate. This means that their presence, at least in Ukraine’s rear areas, could be possible without Russia’s formal approval.

What makes missions effective and why they may fail

One of the most successful peacekeeping missions is considered to be the UNTAG mission in Namibia in 1989-1990. It was deployed to oversee the withdrawal of South African troops and the holding of elections that would lead Namibia to independence. The mission successfully organized the elections in 1989, ensured a peaceful transition to independence, and completed its work. Namibia became a stable democratic state. Importantly, the conflict did not resume afterward. UNTAG had a strong mandate, and international support, including pressure on South Africa.

Another partially successful UN mission was UNFICYP in Cyprus. It was initiated in 1964 and continues to this day. The mission was deployed after clashes between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots and Türkiye's invasion in 1974. UNFICYP managed to maintain a buffer zone between the two communities, preventing large-scale combat for decades. The mission helped de-escalate tensions and supported humanitarian initiatives, but the conflict remains unresolved. The island remains divided between the Republic of Cyprus and the unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Peacekeepers were unable to facilitate a final political settlement or reunification of the island.

There are far more failed missions, and their lessons can be instructive for Ukraine. Perhaps the most relevant example for Ukraine is the UNPROFOR mission in Bosnia, which operated from 1992 to 1995. Peacekeepers were tasked with protecting civilians and ensuring the delivery of humanitarian aid during the war. However, they failed to prevent mass atrocities, including the Srebrenica massacre in July 1995, when Bosnian Serb forces killed over 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in a "safe zone" under the protection of Dutch peacekeepers.

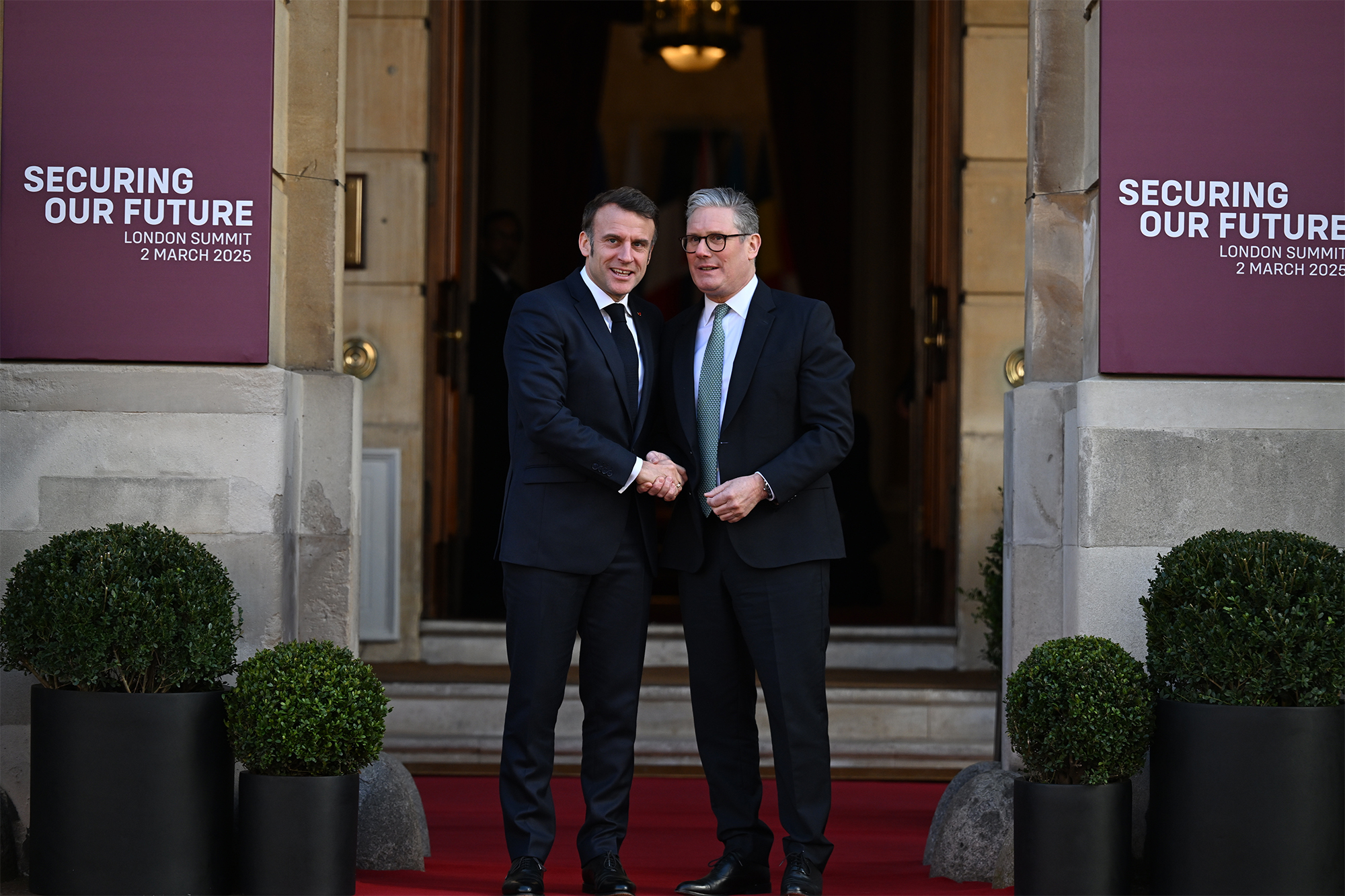

Ukrainian peacekeepers in Bosnia (Photo: archive of peacekeeper Andrii Khlusovych)

Ukrainian peacekeepers in Bosnia (Photo: archive of peacekeeper Andrii Khlusovych)

Overall, limited mandates, lack of weaponry, and the political indecisiveness of the UN Security Council were the main problems of that mission, as Serhii Polyovyk, an expert at the Borysfen Intel Analytical Center, explained to RBC-Ukraine. He was an officer in the liaison group for warring sides of the 240th Separate Special Battalion in several peacekeeping missions in Bosnia. According to him, the situation only improved after UN peacekeepers were replaced by NATO forces.

At the same time, in crises, which will certainly arise with the involvement of foreign troops, much depends on the specific commanders on the ground. While Dutch peacekeepers in Srebrenica watched the mass killings without daring to stop them, in the nearby enclave of Žepa, Ukrainian forces managed to save between 5,000 and 10,000 Bosnian Muslims, Polyovyk shared. Despite a lack of support from the UN headquarters in Sarajevo and limited resources, the Ukrainian military decided to act independently.

Evacuation of civilians from the Žepa enclave in Bosnia (Photo: Getty Images)

Evacuation of civilians from the Žepa enclave in Bosnia (Photo: Getty Images)

"In Srebrenica, the Dutch, to put it mildly, got scared and obeyed the Serbs' order to withdraw and not interfere with them killing Muslims. Our people did not do that. Mykola Yakovych Verhohlyad, our officer, immediately went to meet with Ratko Mladić (the Serbian general, later convicted of war crimes), spoke as an officer to an officer, and after that, the Serb, a bandit, said: 'You are a real officer, you are strong, strong people make agreements with each other, while weak ones have their will dictated to them.' After that, they allowed us to evacuate people in our vehicles and buses," Polyovyk told RBC-Ukraine.

Will the contingent guarantee the security

Even if we set aside the question of the moral and willpower qualities of the peacekeeping force, the key issue remains its size and deployment location. In January, the President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy stated that to prevent a new Russian attack on Ukraine after any ceasefire agreement, at least 200,000 European peacekeepers would be required.

On February 17, The Washington Post wrote that European countries might send between 25,000 to 30,000 troops to Ukraine as part of a peacekeeping mission. According to the media, this number was revealed in response to a letter from the US, where they asked European countries to detail their capabilities to support Kyiv. However, European countries also need to keep troops on other threatening fronts, which imposes its limitations.

“If they decide to deploy, we could likely see some three to five multinational brigades with enablers and air cover – anything more than that would risk seriously weakening NATO’s eastern flank in other places at a time when the credibility of the US commitment to European security seemingly is eroding with every passing day,” said Rafael Loss to RBC-Ukraine.

According to Oleksandr Sayenko, the peacekeeping force must be strong enough to force Russia into peace through military means. Thirty thousand troops are insufficient for this. Moreover, the deployment of this amount of troops on the front line might provide Russia with additional reasons for provocations and speculations.

French soldiers (Photo: Getty Images)

Due to these considerations, a more realistic scenario is the deployment of the peacekeeping force farther from the front line, which is also confirmed by sources in RBC-Ukraine.

“From my point of view, the most effective option is not deploying military contingents but, for example, something like the French gendarmerie – an equivalent of our National Guard, to protect nuclear power stations, for example. And here, Russia’s consent is not required,” Sayenko noted.

Such a peacekeeping force could perform several important functions in Ukraine simply due to its presence.

“The most important thing is to ensure security in the air and at sea. This means air defense/missile defense – possibly with air defense systems or aviation, as well as a naval component, to prevent the cutting off of our sea communication lines. This is the most important thing, and it can be done without risking starting a World War Three, as Trump warns us about,” said Oleksandr Khara, a diplomat and head of the Center for Defense Strategies, in a conversation with RBC-Ukraine.

Serhii Polyovyk added that the very fact of NATO structures being present in Ukraine will be important. Even deep within the territory, it will be ensured with the appropriate information.

“This means that AWACS (Airborne Warning and Control System aircraft) will be flying and that airspace will be patrolled along the line of demarcation and Ukraine’s borders with NATO countries. This will enter the informational space. Whether it will be public is another question, but it will be known what is happening on the Russian side,” said Polyovyk.

The expert emphasized that this would act as a “deterrent factor for the Russians, but it cannot be the dominant element to change Russian decisions or actions if they decide to continue aggression.”

However, there cannot be talk of security guarantees. According to Khara, the placement of European troops on Ukrainian territory will not fall under Article 5. It will fall under Article 6, which does not involve NATO in the war if Russia attacks the peacekeeping force.

“When they talk about security guarantees, including our government, they are misleading the Ukrainian public. Security guarantees can consist of several elements. The first is nuclear deterrence, the second is collective security, i.e., Article 5 (an armed attack on one NATO member is considered an attack on all members). No one in the West wants to give us that because they don’t want to take on such risks,” Khara said.

Overall, Ukraine’s European partners have begun to think more about their own security, no longer taking the "security umbrella" from the US for granted. Meanwhile, the issue of the peacekeeping force in Ukraine is one of the components of this security. However, even the boldest politicians in Europe are not yet ready to take risks and are not considering deploying their troops on Ukraine’s side, which could significantly change the situation. Half-measures that may be implemented will only slightly ease Ukraine’s situation but will not guarantee protection from renewed Russian aggression.

Sources: statements from the leadership of Ukraine, France, and the UK, publications from Reuters, CNN, Politico Europe, Le Figaro, BBC, Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and comments from Oleksandr Sayenko, SerhiyiPolyovyk, Oleksandr Khara, and Rafael Loss.

UN peacekeeper in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: Getty Images)

UN peacekeeper in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Photo: Getty Images)