Way home. War - not the only threat to Ukrainian unity

A Ukrainian IDP at the train station in Przemyśl, Poland (photo: Getty Images)

A Ukrainian IDP at the train station in Przemyśl, Poland (photo: Getty Images)

The risks of Ukraine losing millions of citizens abroad and the prospects of their return home - in the article below.

In the address shortly before Independence Day, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced establishing a new institution - “in fact, the Ministry of Ukrainian Unity.” The idea is that it should take care of the millions of Ukrainians who are abroad.

As for the approach itself, one can argue whether it is really necessary to create a new separate bureaucratic structure and whether the resources invested in its establishment will correspond to the results achieved. After all, the joke that “if the Ministry of Black Soil is created in Ukraine, black soil will disappear in Ukraine” did not appear out of thin air. Skepticism about the Ukrainian state apparatus has a solid foundation that has been strengthened over the decades.

But the president outlined the main problem correctly - indeed, “we have never had such a part of our people abroad before." And something must be done with this part of the people because the problem of unity will not be solved by itself.

Will millions of those who left Ukraine because of the war return home after at least the active phase of hostilities is over? No sociology is relevant here, because of the tendency of people to give a socially approved answer and emphasize their patriotism, because being a patriot is an unambiguous mainstream of public opinion.

RBC-Ukraine's sources in the highest echelons of government are rather skeptical about the prospects of Ukrainians returning home after the war. In short, the general answer is vague: some will return, and some will not.

Over time, the proportion will continue to shift in favor of the second option. It cannot be otherwise. Ukrainians are getting better and better at settling into the new land, learning the language and customs, getting used to the alien mentality, finding jobs, children going to schools and universities, and normal socialization. Nostalgia for affordable medical services in Ukraine, native cuisine, and high-quality Internet banking is unlikely to convince those who decided to seek a better life abroad and start life anew in a foreign land to return home.

The ties are being cut off not only with Ukraine as a state, but also inside the families - probably every Ukrainian can recall examples of relatives, friends, and acquaintances whose families have failed the test of distance and time.

It's not just about those who sought refuge from the war after the Russian invasion in February 2022 and chose Western countries. It is also about those who, of their own free will or under duress, have been rooted in the aggressor country since 2014 or have remained in the territory occupied for more than 10 years. Unfortunately, it is also about millions of people - Ukrainians who have remained on the other side of civilization.

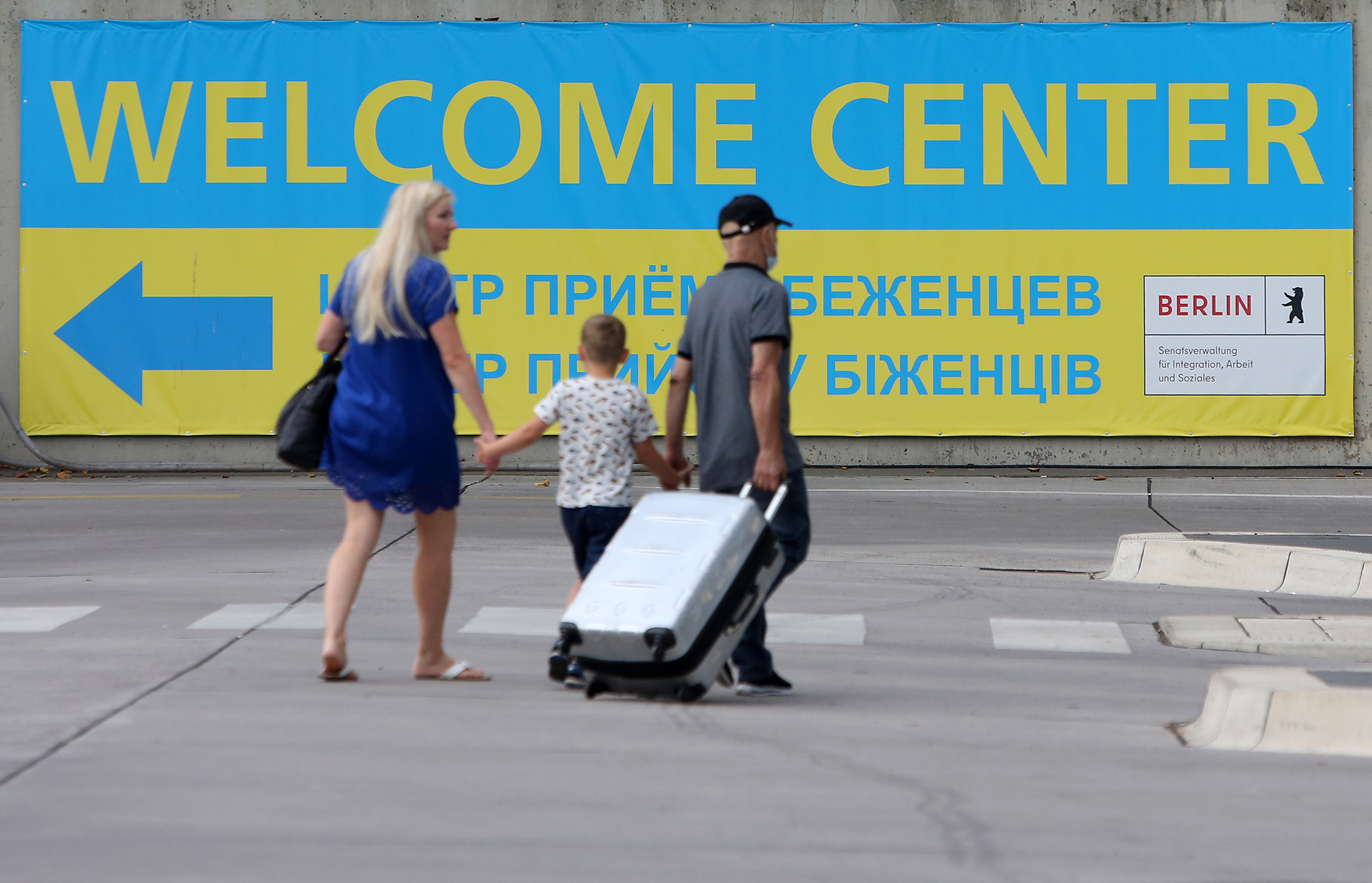

IDPs in Berlin (photo: Getty Images)

The gap between them and the rest of the country has been growing for a decade. Time and separation from relatives, friends, and ultimately a reality not distorted by Russian propaganda are also taking their toll. The comments of Ukrainian politicians and government officials, which sometimes contradict each other (for example, on passportization in the occupied territories), hardly add to the confidence that someone somewhere in high government offices has a plan.

Even after February 24, 2022, did the state have any well-thought-out refugee policy? Most likely not. Except for some separate, not always well-coordinated actions. They are aimed not so much at ensuring unity between those who are “here” and those who are “there” as at solving the main current problems.

One of them, which has become even more acute this year, is human resources, primarily to continue defense against Russian aggressors, as well as to ensure the functioning of the economy, again for the needs of the front. “One day I will have to ask myself the question: who am I? I will have to make a choice who I want to be. A victim or a victor? A refugee or a citizen?” Zelenskyy said in his New Year's greetings in 2024 to those who are now abroad.

After the appeal to civic feelings did not help, and the mobilization campaign began to gain momentum, other tools were used to influence those who were liable for military service and had left Ukraine by all means (most often - illegal), such as the imposition of various restrictions on consular services. In Western capitals, this caused “riots of evaders,” and in Ukraine, it led to cruel jokes about the “Warsaw battalion.” The campaign did not have stunning results.

After the war is over, the emotional gap between those who stayed in Ukraine and those who left it may not be felt as sharply, but it will not go away. Again, because someone was in Ukraine all the time, even if not in the army, but experienced shelling, air raids, and blackouts. And someone was “over there,” complaining on social media about the poor level of digitalization compared to Ukraine. At least, these are the arguments that will definitely surface and are already being heard.

But artificially fueling the confrontation between the two parts of Ukrainians is definitely a road to nowhere. As ancient advice says, a problem should be turned into an opportunity.

And a huge number of Ukrainians abroad is just an opportunity when most of them will eventually settle in new countries. The Ukrainian diaspora, especially in Western countries (where most of them left), can become a powerful lever of influence for Kyiv. Just like the Irish diaspora in the United States or the Armenian diaspora in France, where they can significantly influence the policies of their countries of residence.

Ukraine also has similar examples, although not as vivid, such as Ukrainians in Canada, the vast majority of whom have been migrants for several generations. And even though, for example, Donald Vasyliuk from Toronto feels much more like Donald than Vasyliuk, and may not even know Ukrainian at all, at a critical moment, like during a full-scale war with Russia, he can still go to a rally and put pressure on his government from below.

There is also an alternative, less desirable reality in which the unity of the nation and the support of the diaspora can only take place at Polish and German stadiums during away games of Dynamo Kyiv or the national football team. This will not help the country, which is torn and tired from the war, and will only cause irritation and anger.

Although time and distance are still playing against Ukrainians, there is hope that the Ukrainian reality will be more welcoming and that everyone, wherever they stay, will always remember where they came from and will not forget the way home.