6 historical mysteries that scientists finally unraveled in 2023, except 1

What historical mysteries were uncovered in 2023 (photo: GettyImages)

What historical mysteries were uncovered in 2023 (photo: GettyImages)

Modern technologies have unlocked the ability to investigate DNA preserved for thousands of years in bones, while artificial intelligence can decipher ancient texts written in long-forgotten scripts. All of this enables scientists to unravel mysteries that have long perplexed humanity.

Six historic breakthroughs of 2023, according to CNN.

True identity of a prehistoric leader

Buried with a striking crystal dagger and other precious artifacts, the 5,000-year-old skeleton discovered in 2008 in a tomb near Seville, Spain, was evidently someone of importance.

Initially believed to be a young man based on pelvic bone analysis, scientists later determined, through an analysis of dental enamel containing a sex-specific protein called amelogenin, that the remains belonged to a female.

A crystal dagger was buried with the body of a 5,000-year-old woman (photo: Research Group ATLAS from University of Seville)

The ingredient of the legendary strong Roman concrete

It turns out that Roman concrete is more durable than its modern equivalent, exemplified by structures like the Pantheon in Rome, boasting the world's largest unreinforced dome.

Scientists claimed to have uncovered the mysterious ingredient that allowed the Romans to create such robust building material, enabling them to construct intricate designs in challenging locations such as docks, sewers, and seismic zones.

A research team analyzed 2,000-year-old concrete samples taken from the city wall at the archaeological site of Privernum in central Italy. The samples were compositionally similar to other concrete found throughout the Roman Empire. They found that white flecks in the concrete fragments of lime endow the concrete with the ability to self-heal cracks that develop over time. Previously, these white flecks were overlooked, often dismissed as signs of sloppy concrete mixing or inferior raw materials.

The real appearance of Ötzi - the Iceman

In 1991, tourists discovered the mummified body of Ötzi high in the Italian Alps. His frozen remains are arguably the most thoroughly studied archaeological find in the world, providing scientists with detailed insights into life 5,300 years ago.

The contents of his stomach allowed scientists to understand his last meal and where he came from. His weaponry revealed that he was right-handed, and his clothing provided a rare glimpse into the fashion of ancient people.

In August, a new DNA analysis extracted from Ötzi's pelvis showed that his appearance was different from what scientists initially believed.

The study of his genetic makeup indicated that Ötzi had dark skin, dark eyes, and was likely bald. This updated appearance sharply contrasts with the well-known reconstruction of Ötzi, which depicts a fair-skinned man with thick hair and a beard.

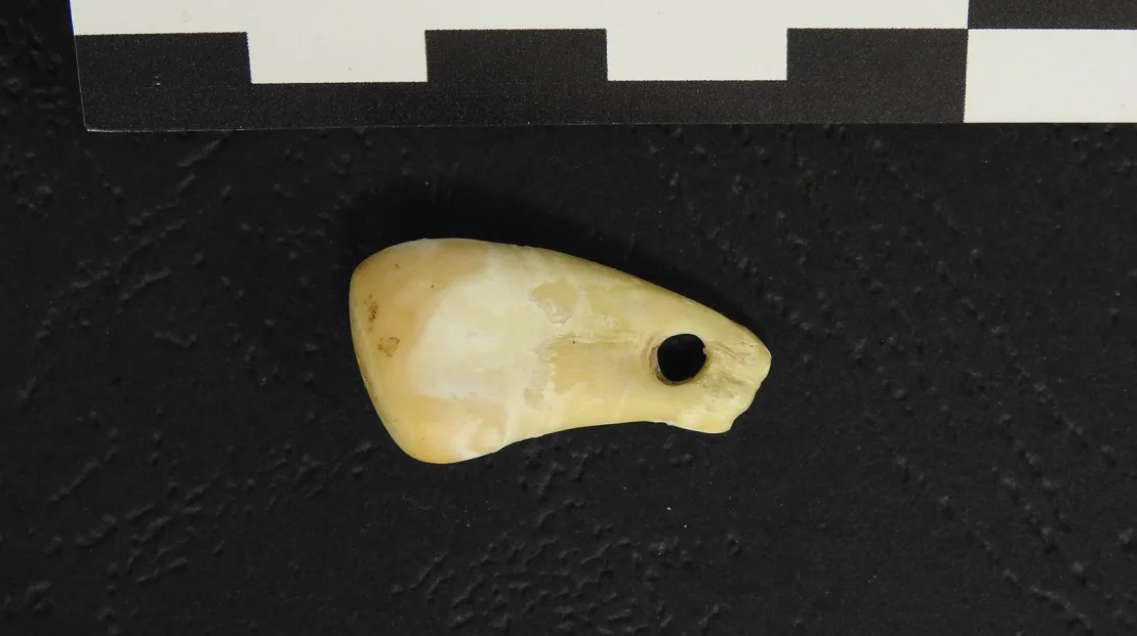

Owner of a pendant dating back 20,000 years identified

Archaeologists often find bone tools and other artifacts at ancient sites, but it's challenging to precisely determine who once used or wore them.

Earlier this year, scientists reconstructed the DNA of an ancient human from a pendant made of deer bone found in Denisova Cave in Siberia. Using this clue, they were able to identify that it was worn by a woman who lived between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago.

She belonged to a group known as ancient North Eurasians, genetically linked to the first Americans.

Human DNA likely survived in the deer bone pendant because it is porous, making it more likely to preserve genetic material present in skin cells, sweat, and other bodily fluids.

The pendant with a deer tooth contained DNA left by its owner (photo: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology)

Ancient Sumerian script deciphered

About 1,100 scrolls were charred during the famous eruption of Mount Vesuvius almost 2,000 years ago. In the 1700s, some determined excavators discovered a massive repository of volcanic ash.

The collection, known as the Herculaneum Papyri, is arguably the largest known library from classical antiquity. The contents of these fragile documents remained a mystery for a long time. However, this year, with the help of artificial intelligence and computerized tomography imaging, student Luke Farritor successfully deciphered a word written in Ancient Greek on one of these charred scrolls.

Farritor was awarded $40,000 for deciphering the word πορφυρας or porphyras, which translates from Greek to purple. Researchers hope that it won't be long before the entire scrolls can be decoded using this technique.

Materials needed for making a mummy

From fragments of discarded pottery in an embalming workshop, scientists have identified substances and mixtures that ancient Egyptians used for mummifying the dead.

Through chemical analysis of organic residues left in the vessels, researchers found that ancient Egyptians used a wide range of substances to anoint the body after death, reduce unpleasant odors, and protect it from fungi, bacteria, and decay. The identified materials include plant oils such as juniper, cypress, and cedar, as well as resins from pistachio trees, animal fat, and beeswax.

While scientists had previously learned about the names of substances used for mummification from Egyptian texts, until recently, they could only speculate about the specific compounds and materials involved.

The ingredients used in the workshop were diverse and came not only from Egypt but also from distant lands, indicating long-distance trade in goods.

Artist's reconstruction of the embalming scene with a priest in an underground chamber (photo: Nikola Nevenov)

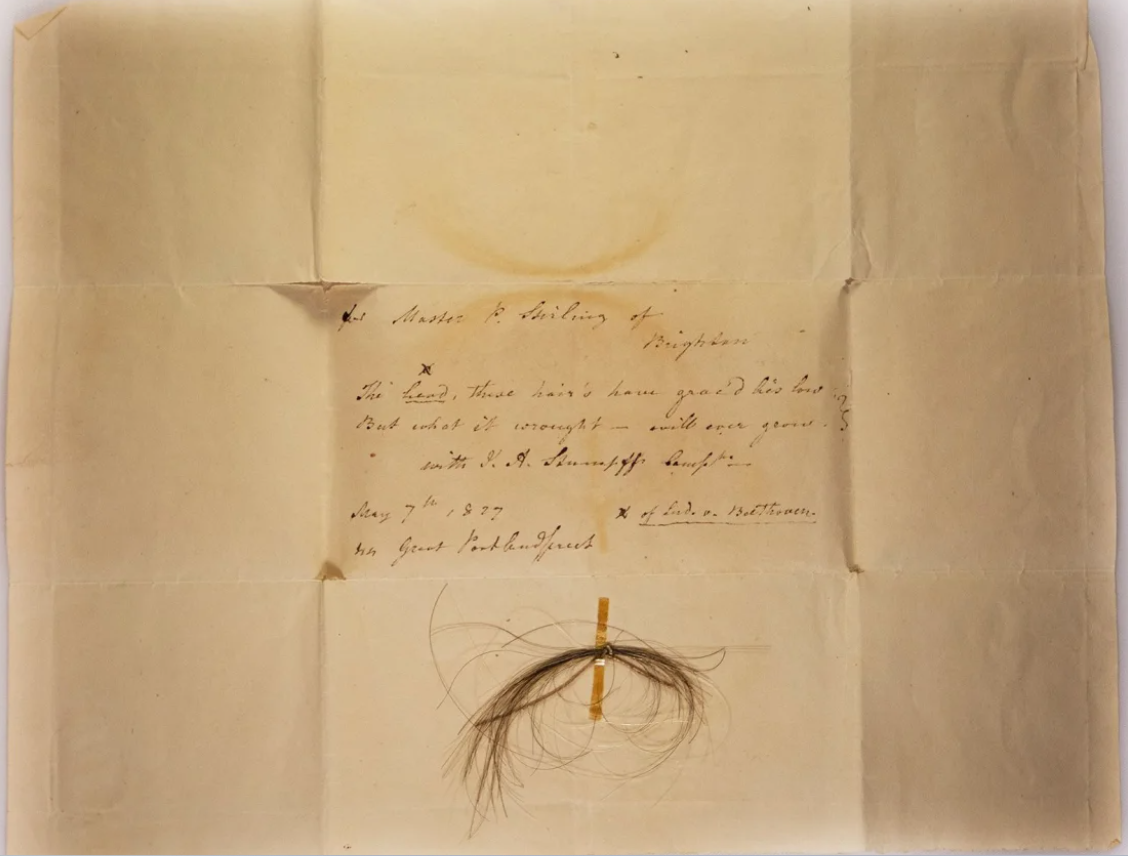

One family secret of Beethoven revealed, while another remains a mystery

Composer Ludwig van Beethoven passed away at the age of 56 in 1827, following a series of chronic health problems, including hearing loss, gastrointestinal issues, and liver disease.

In 1802, Beethoven wrote a letter to his brothers requesting that his physician, Johann Adam Schmidt, investigate the nature of his illnesses after his death. This letter is known as the Heiligenstadt Testament.

The medical team couldn't provide a definitive diagnosis, but Beethoven's genetic data helped researchers rule out potential causes of his illnesses, such as autoimmune disorders like celiac disease, lactose intolerance, or irritable bowel syndrome.

Genetic information also revealed an extramarital connection within Beethoven's family.

Nearly 200 years after his death, scientists extracted DNA from a preserved hair strand, attempting to fulfill his posthumous request.

Lock of hair from which Beethoven's entire genome was sequenced (photo: Kevin Brown)